Heavy-Duty Engine Design

Increasing regulations and market demands call for cleaner, more durable and fuel-efficient engines. Developers rely on CAE simulation, enhanced test methods and 3D printing to keep up.

Developing heavy-duty engines involves the management of competing needs and resources. “These include competing requirements, complex and non-harmonized global emissions regulations, and global customer needs,” said Allison Plunkett, Manager, Application Design and External Application Engineering, John Deere Power Systems (JDPS). She was speaking in the SAE technical webinar on Heavy-Duty Engine Design, first aired in June 2018 (on-demand viewing available here ).

3

Makers of off-highway equipment such as John Deere may have the most challenging engineering problem sets in history. JDPS industrial engine lineups must range from 40 hp (30 kW) to 600 hp (447 kW) while satisfying multiple market segments, such as agricultural, turf, forestry, and construction.

“Within the agricultural and turf products, there are over 100 applications among the product lines including tractors, combines and cotton pickers,” each having its own unique requirements, Plunkett noted. These requirements involve packaging, how the product is used, and its environment — machines could run in arctic or desert conditions, or the humid Midwest. However, the basic engine architecture must be common to contain manufacturing and servicing costs.

Fortunately, while these engineering requirements have grown in complexity, so have simulation and system-modeling tools grown in power.

Model-based systems development

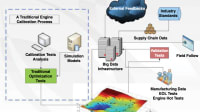

Engineers now can simulate in bits and bytes what they used to have to test in expensive physical prototypes. “For new engines, we gather data on operation cycles, country, altitude, and many other needs. We then translate these needs into product requirements using systems engineering principles,” Plunkett explained.

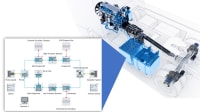

A requirements wish list is only the start. Can they be met? Are they compatible with each other? To answer those questions, JDPS now relies on model-based development to validate them against reality and each other. The company’s model-based engine development toolkit includes engine combustion modeling, optimization based on simulation, finite element analysis, computational fluid dynamics, and so-called 1D or system models.

“By understanding requirements and the many improvements in analytical methods, engineers are able to design for the customer, including traditional packaging and performance but also reliability, manufacturability, and serviceability — long before tools are cut,” she said. “Model-based development has evolved to include full tool chains to improve accuracy. Using component requirements and modeling, we can validate requirements on the full engine.”

Simulation comes of age

Why has computer simulation emerged as such an important tool? “Computer speed, memory and parallelization has improved,” Sameera Wijeyakulasuriya, PhD, principal engineer, applications for Convergent Science, explained in the SAE webinar.

Clever software minimizes the computation needed for combustion and fluid dynamics simulations. A good example is Convergent Science’s own flagship software, Converge CFD. It has greatly streamlined the simulation of in-cylinder combustion and gas exchange. With features like autonomous and gradient meshing, among others, it uses the minimum number of computational cells to get an accurate answer, providing answers in a practical turnaround time.

Wijeyakulasuriya pointed out two important areas where simulation physics has made strides recently — advanced fuel injection modeling and emissions. Emissions includes both engine-out predictions and aftertreatment chemistry.

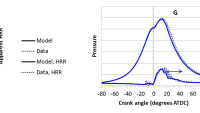

“In heavy-duty engines, accurate emissions predictions require accurate cylinder pressure and heat release rate predictions,” he said. For simulations to be useful in this regard, they must also include a chemical mechanism that includes accurate NOx chemistry. “EGR [exhaust gas recirculation] has a significant impact on NOx; thus, it is important to capture composition and mass of internal and external EGR,” he explained.

Another tool that Convergent Science offers is in determining where significant urea deposits may form inside selective catalytic reduction (SCR) units. This is what Wijeyakulasuriya termed a “risk model” that can guide design decisions.

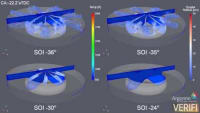

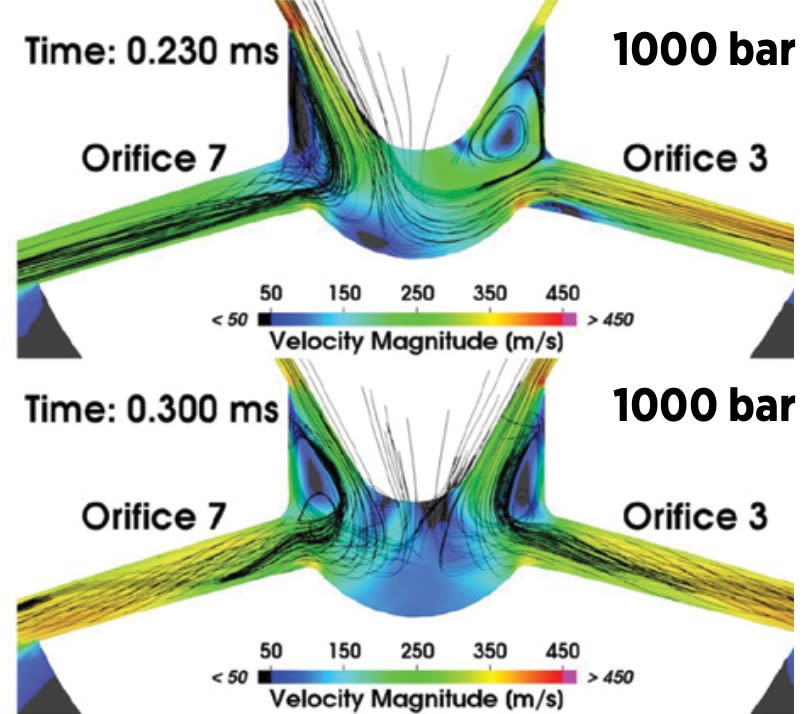

Numerical simulations are now giving engineers more insight than ever on 3D flow and combustion, especially in modeling how advanced fuel injectors can improve combustion. “For example, [we can now see] how fuel dribbling from an injector increases unburned hydrocarbon emissions,” he said.

Today’s capability provides fuel injection modeling based on nominal geometry (think CAD models), various forms of unsteady turbulence modeling, and mesh models that can run up to 20 million cells to predict the flow of fuel from a direct injection nozzle. The future — which he thinks is not that far off — will include actual geometries based on x-ray scans (today available from government labs), refined turbulence models that can provide high-fidelity predictions of turbulent flow, and computational models of 100 million or more cells. These advanced capabilities will begin to predict variation, such as shot-to-shot variability, cavitation erosion, and fluid-structure interactions.

Simulation results also provide deeper insight into combustion events and fluid flow in ways physical testing cannot do. How so? Simulated data can be presented in creative ways, often deep into the phenomenon where no physical sensor or camera could go. These include detailed color maps, simulated movie clips, and slices of data deep in cylinders.

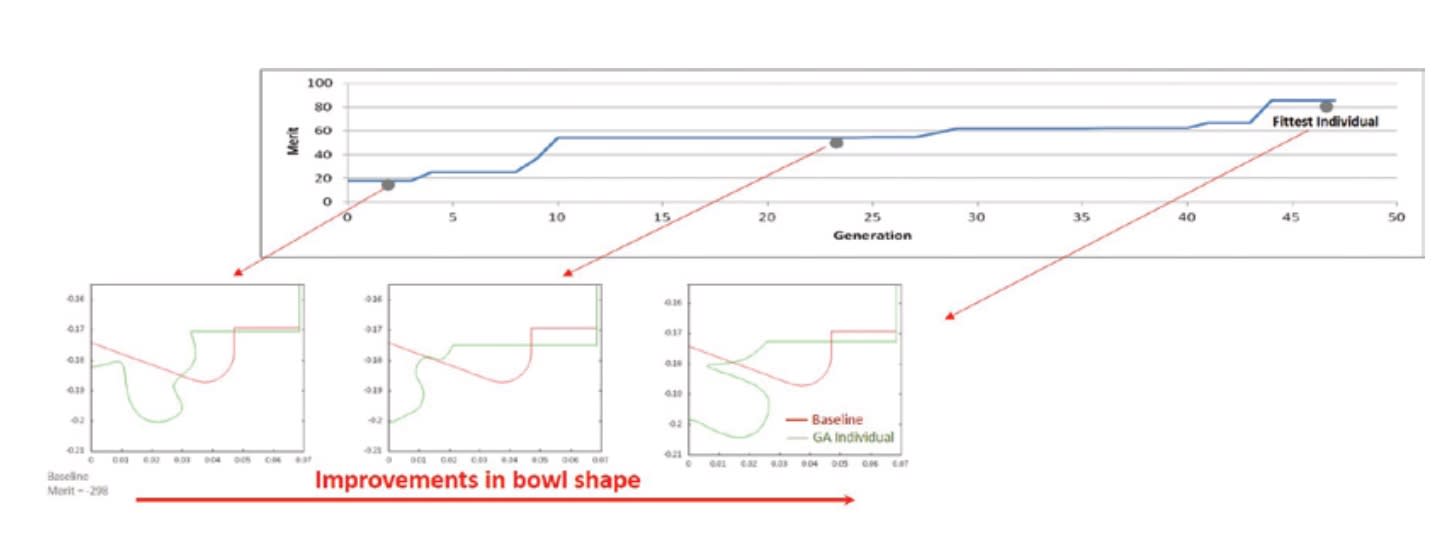

More importantly, simulation tools are moving on from simply replacing testing. They can now aid design with optimization techniques and genetic algorithms. In the SAE webinar, Wijeyakulasuriya presented results on how a genetic algorithm improved a piston bowl geometry in a somewhat surprising way to minimize fuel consumption without exceeding emissions or peak cylinder pressure. As computers get more powerful, and engineers learn more about these capabilities, expect more such revelations in the future.

Testing redefined: exploiting the Internet of Things

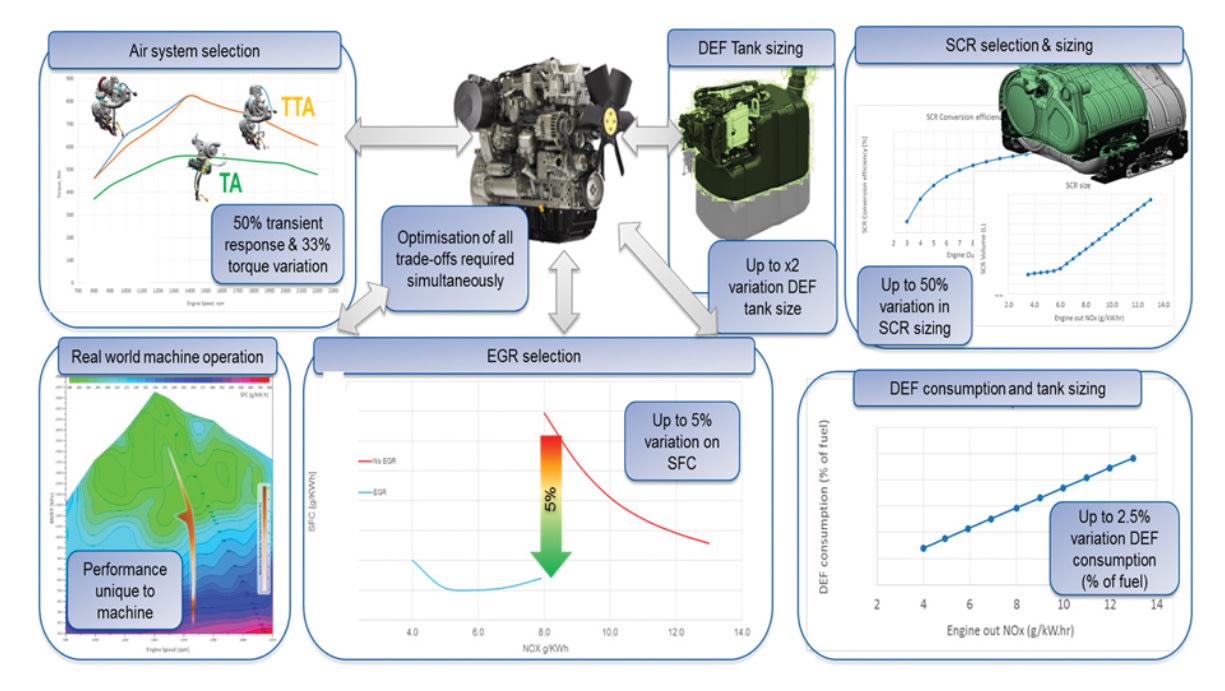

Perkins Engines, as a maker of off-highway diesel engines from 6 to 600 kW (8 to 805 hp), has much the same challenge as JDPS — balancing competing requirements, worldwide and non-harmonized regulations, and a stunningly complex engine lineup to meet various applications. Defining customer satisfaction is easy to say, but complex to do, when engineering products for more than 800 customers who are sourcing the same base engine for use in over 3,000 different machines.

“Historically, ‘testing’ has been thought of as the part of a program after the design stage once metal has been cut, prototypes have been built, and working engines are available to test power, durability and specific failure modes,” said James Reed, CEng, Technical Sales Manager, Perkins Engines, during the webinar. “But as time has moved on, improved computing methods have enabled us to apply analytical techniques to all stages of an engineering program.”

Like JDPS, Perkins uses a full suite of CAE and system-modeling tools for early design work and requirements validation, developing torque curves and transient responses of future engines that will meet customer requirements. Interestingly, he also noted that the industry is still using mostly empirical methods to assess the trade-off between engine-out NOx control and aftertreatment reduction.

The company also tracks and compiles data by exploiting the emerging Internet of Things (IoT). “We’re now using telemetry data to assess the real duty cycles of machines in operation,” he explained. “In this case, more than 100,000 machines with over 300 million hours of data.”

This provides a real-world view of fuel burn rates, ambient conditions and number of key cycles with which Perkins can further refine its technology choices, according to Reed. “We have created a database of machine cycles that we have found represent the validation needs of all machine types, as well as the distribution of ambient conditions encountered in the real world to ensure that good performance trade-offs are made as we refine and calibrate the design.”

He also noted there are always situations where a machine is being used outside its normal operating mode. “For example, an excavator may spend 80 percent of the time on a digging cycle, but 20 percent of the time being used to lay pipelines,” he said. Often, in those cases they find that the operation of one of the other machine types covers that “exception” and as a result, the validation cycles are robust to these variations.

Top Stories

NewsRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsPower

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

ArticlesAR/AI

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Automotive

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Automotive

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Energy

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance