How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

Airbus is using wire‑directed energy deposition (w‑DED) to 3D print titanium aircraft parts at much larger scales than earlier additive manufacturing methods allowed. Some of the w-DED parts are already being integrated into in-production aircraft — such as the A350 — according to an overview of the new 3D printing technique published on the company’s website.

How Does w-DED Work?

W-DED is a new approach to additive manufacturing with titanium that creates create structural aircraft parts with less resulting material waste, compared with the traditional subtractive methods such as machining from plate or forging.

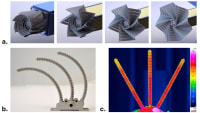

The technique uses a multi-axis robotic arm, armed with a spool of titanium wire, moving with digital precision. Energy, in the form of a laser, plasma, or electron beam is focused onto the wire, instantly melting it and fusing it layer-by-layer onto a surface. Superficially similar to welding, but with a 3D model as its guide, it prints the object from the ‘ground up’ into what is known as a ‘blank.’ This blank looks very much like the final required shape, i.e. ‘near net shaped’, which subsequently undergoes a quick machining to conform to the exact dimensions of the part design.

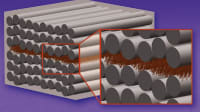

While 3D printing with metals in aerospace has been used for around a decade, up until now it has mostly been used for smaller components. These conventional systems, called ‘powder-bed’ printers, were typically optimized for making parts that are less than two feet long.

w-DED, on the other hand, allows Airbus to move from printing small components to creating large, structural titanium parts up to seven meters (over 23 feet) long. The new process promises to be faster than powder-bed 3D printing, boosting production from hundreds of grams per hour to several kilograms per hour. This leap could make 3D printing viable for industrial, high-volume manufacturing of large structural components for commercial aircraft.

Reducing Titanium Raw Material Waste

Why focus on titanium? While the metal is essential for aircraft due to its strength, lightness, and compatibility with modern carbon fiber composite structures, titanium is also a high-value raw material. So conserving it is paramount.

Consider that traditional forging — i.e. machining a part from a solid block — creates a high proportion of raw material ‘waste’. This is measured by the ‘buy-to-fly’ ratio — the amount of raw material purchased versus the amount that actually ‘flies’ in the aircraft. In traditional methods, one might need to recycle between 80 percent and 95 percent of the titanium originally bought.

With w-DED, such waste is mostly prevented at source. This is because the part is ‘grown’ into a shape that is already very close to the final design (a ‘near net shape’), there is very little left to machine away.

Traditional die forging also requires the creation of large, complex tooling that can take up to two years and require a large up-front capital investment. By contrast, a 3D-printed part's shape is determined by a computer program, reducing the lead time to just a few weeks. w-DED’s agility will be of immediate benefit to the successful and timely construction of the first development aircraft, especially while the final detailed component designs are being tweaked and optimized, right up to the point when the first aircraft starts to take physical shape.

Airbus has recently started serial integration of largest w-DED parts into the A350’s Cargo Door Surround area. These particular Airbus-designed parts for this exploratory phase were 3D-printed by a qualified supplier using plasma w-DED, ultrasonically inspected by Testia Bremen and finally machined and installed in Airbus factories.

These parts are functionally and geometrically identical to the traditional forged components they replace, but they deliver immediate, real-world cost savings. Looking forward, the next aim is to progress, step by step, from the A350 w-DED parts and into more critical applications on other programs and other aircraft applications (including the wings and landing gear in the longer term).

Importantly, this technology enables a concept called "designed for DED." Instead of having engineers design a complex component as an assembly of several separate pieces that must be joined together, they can now design it as a single, intricate and optimized component that is printed all at once. This ability to merge multiple components into one will simplify the supply chain, reduce assembly labor, shorten cycle time and unlock the full potential of the next generation of 3D-designed airliners.

Today at Airbus, the race to accumulate experience of w-DED for critical parts is well underway, with very promising success. Engineers are testing various energy sources, including plasma, arc welding, electron- and laser beam, and simultaneously evaluating “Buy” (outsourcing the printing) and “Make” (doing it in-house) strategies. Moreover, being governed as an Airbus ‘group’ level approach, the resulting technologies will be an industrial standard and usable across the company.

Top Stories

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() Rewriting the Engineer’s Playbook: What OEMs Must Do to Spin the AI Flywheel

Rewriting the Engineer’s Playbook: What OEMs Must Do to Spin the AI Flywheel

Road ReadyTransportation

![]() 2026 Toyota RAV4 Review: All Hybrid, All the Time

2026 Toyota RAV4 Review: All Hybrid, All the Time

NewsDesign

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() F-22 Pilot Controls Drone With Tablet

F-22 Pilot Controls Drone With Tablet

EditorialLighting Technology

Webcasts

Energy

![]() Powering America’s EV Future: Connect, Collaborate, Innovate

Powering America’s EV Future: Connect, Collaborate, Innovate

Power

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Transportation

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...