Combustion Modeling in Heavy-duty Diesels

A focus on the development of a CFD methodology for combustion simulations took two different approaches to model flame propagation, both of which employed detailed chemistry and turbulence chemistry interaction. The first, MRIF, assumed that diesel spray combustion can be represented by a set of laminar diffusion flames, while in the second model the flame structure is described by multiple homogeneous reactors with turbulence-chemistry interaction.

Diesel engines have found their way into most heavy-duty applications in the stationary, construction, industrial, and agriculture industries. They have a high power density and can easily operate on a large range of speeds and loads. However, to meet new emissions standards and reduce fuel consumption, continuous R&D is needed in different areas including combustion, engine turbocharging/downsizing, and aftertreatment systems.

The combustion process will continue to play a central role since it affects both cycle efficiency and the quality of exhaust gases that are later cleaned up by the aftertreatment systems. To this end, both advanced numerical and experimental tools are necessary to investigate how the flame propagates under conventional, advanced combustion modes and at full load conditions when cylinder and injection pressures are very high and a strong interaction between flame and walls is expected. For what concerns numerical models, it is now widely accepted that complex chemistry should be included for a proper prediction of auto-ignition, flame structure evolution, soot, and NOx emissions formation.

An interest in modeling

Interest in combustion modeling in diesel engines can be seen by the large number of approaches proposed over the years. When focusing on the ones based on detailed kinetics, it is important to understand how their performance and predictive capabilities are affected by the assumed flame structure and the way reaction rates are computed.

Homogeneous reactor, partially stirred reactor, unsteady stretched diffusion flame, and transported probability density function were proposed over the years as possible flame structure configurations where auto-ignition and mixing-controlled combustion take place.

Because of the fact that turbulence-chemistry interaction must be included, research is mainly carried out on understanding what the mechanisms are leading to the flame stabilization process. Handling detailed kinetics is another important issue due to the large number of species involved and the time scales that are smaller than that of the flow.

For this reason, chemistry and fluid dynamics are always decoupled and reaction rates are computed by two possible solutions defined as direct integration or pre-tabulation. In the first case, a stiff solver takes the chemical composition at any node (CFD mesh, flamelet domain, or particle) and integrates it according to the reaction rates computed from the kinetic mechanism using time-steps of the order of 10-9 to 10-7. Advantages of such an approach are mainly represented by its flexibility with respect to fuel type, chemical mechanism, and operating conditions.

On the other hand, it is very computationally demanding, and, to be used for practical calculations, suitable tabulation or mechanism reduction algorithms should be applied in combination.

In pre-tabulated approaches, either reaction rates or chemical compositions are stored in an existing look-up table as function of state variables being mixture fraction, temperature, pressure, scalar dissipation rate, and a combustion progress variable. On the basis of such quantities, their variances, and a presumed probability density function, it is possible to compute local composition or reaction rates in each computational cell.

Among the proposed approaches for chemistry tabulation that were applied in the past for diesel combustion were the ILDM (intrinsic low-dimensional manifolds) method and tabulated diffusion flamelets. Another interesting approach is the so-called premixed-diffusion manifold, which has, in principle, the potential to predict flame propagation under the combined premixed and diffusion modes.

Tabulated kinetics is computationally very efficient and it was successfully applied in the past to simulate different flame configurations, mainly at constant-pressure conditions. However, combustion in internal-combustion engines takes place in a wide range of thermodynamic states and, accordingly, a much larger table is necessary, increasing the CPU time needed for its generation and requiring proper storage and retrieval techniques to efficiently access the table data.

Furthermore, computed results depends on the table resolution, and the way progress variable is defined might influence prediction of the autoignition process. To improve the existing approaches, a consistent comparison among different combustion models is necessary and was recently encouraged in the context of the Engine Combustion Network (ECN).

Rolling up the sleeves

In this study, researchers from Politecnico di Milano, FPT, and Dacolt International set out to compare two different approaches that can be used for simulation of combustion process in diesel engines. Both of them include turbulence-chemistry interaction, were implemented in the same open-source code, and were validated both with constant-volume and engine combustion experiments.

The first combustion model is known as MRIF (multiple representative interactive flamelets) and approximates the flame structure as a set of multiple unsteady laminar diffusion flames (flamelets), with their evolution computed in the mixture fraction space where species and energy equations are solved. The effects of mixing are incorporated in the scalar dissipation rate, which is calculated as a conditional average of its distribution in the CFD domain. The use of multiple flamelets ensures a better prediction of both flame structure and auto-ignition, since spatial variations of the scalar dissipation rate are properly taken into account.

The second model is called Dacolt PSR+PDF and is based on tabulated chemistry: it was previously validated with 3D CFD simulations of diesel spray flames on the ECN Spray H (n-heptane) experiments. The combustion model has two main ingredients: the flamelet generated manifold (FGM) chemistry reduction technique, in this case based on auto-ignition trajectories of homogeneous fuel/air mixtures, computed with detailed chemical reaction mechanisms, and presumed-PDF turbulence-chemistry interaction modeling.

The proposed approaches for combustion modeling were implemented in the Lib-ICE code, which is based on the OpenFOAM technology and includes suitable libraries and solvers for simulation of gas exchange, fuel-air mixing, and combustion in internal-combustion engines.

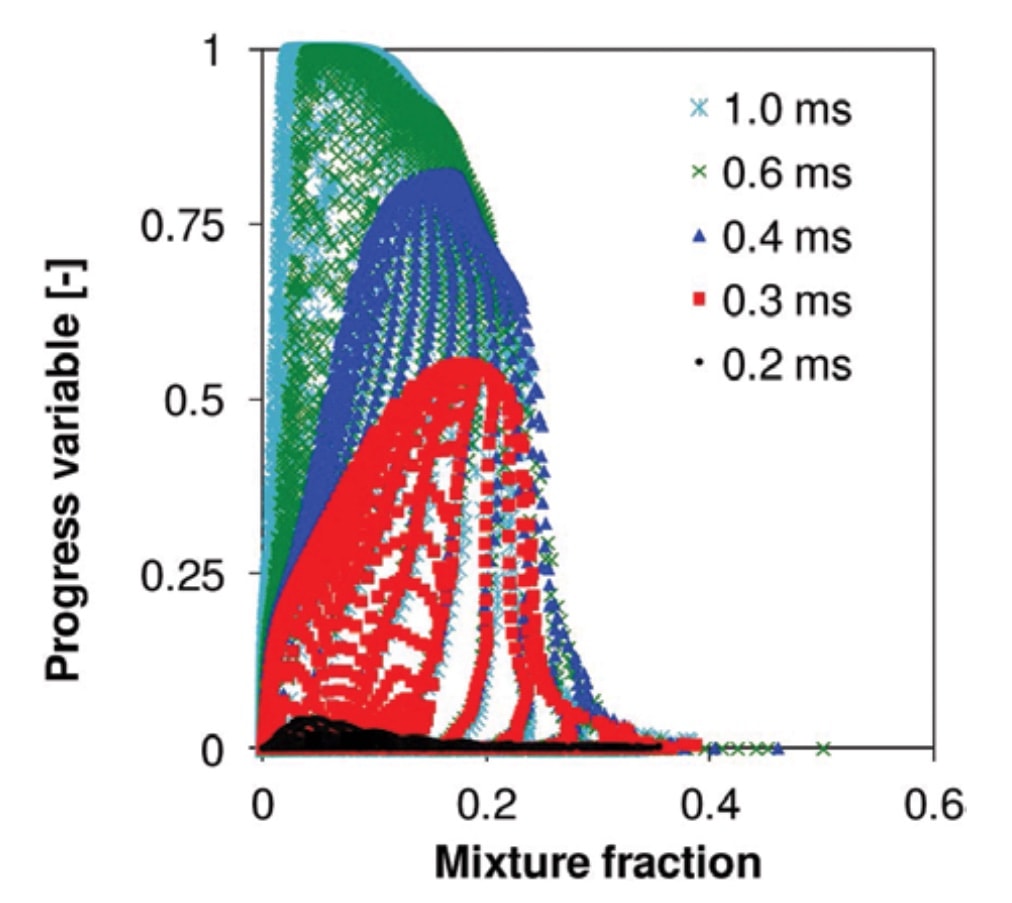

Validation of combustion models for diesel engines is a complex issue and for this reason a suitable methodology was identified: first spray and combustion models were assessed at constant-volume conditions. In particular, the so-called Spray-A experiment suggested by the ECN was simulated at different ambient conditions and validated with available experimental data of jet penetration, mixture fraction distribution, auto-ignition, and flame lift-off length. A detailed analysis of computed results and flame structure allowed the researchers to identify the best approaches.

Afterwards, the combustion process was simulated in a heavy-duty diesel engine, considering five relevant operating points. There, attention focused on model capability to predict heat release rate, wall-heat flux, and cylinder pressure.

Heavy-duty engine simulation

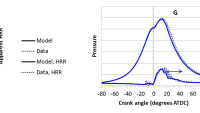

When focusing on the combustion process, both models accurately predicted the initial combustion phase where transition from auto-ignition to mixing controlled flame propagation takes place in the -10 to TDC crank angle interval.

The MRIF model has an earlier ignition compared to the PSR+PDF and this partially explains why pressure was slightly over predicted by such model. Steady-state values of heat release rate profiles are different for the two models, with the PSR+PDF values higher than both MRIF and experimental data probably because of the definition of progress variable or resolution of the table.

There is always a strong connection between injected fuel mass flow and heat release rate. In particular, the injection profile for the full-torque operating condition (A100; four other operating conditions were considered) has a local maximum right before its end. This is responsible for the final peak of heat release rate that is not properly predicted by the two tested combustion models. Possible explanations for this can be found in the chosen turbulence model and the mesh layout used close to the nozzle, which are probably not able to describe correctly the amount of air entrained in the jet when injection ends and the spray momentum is low.

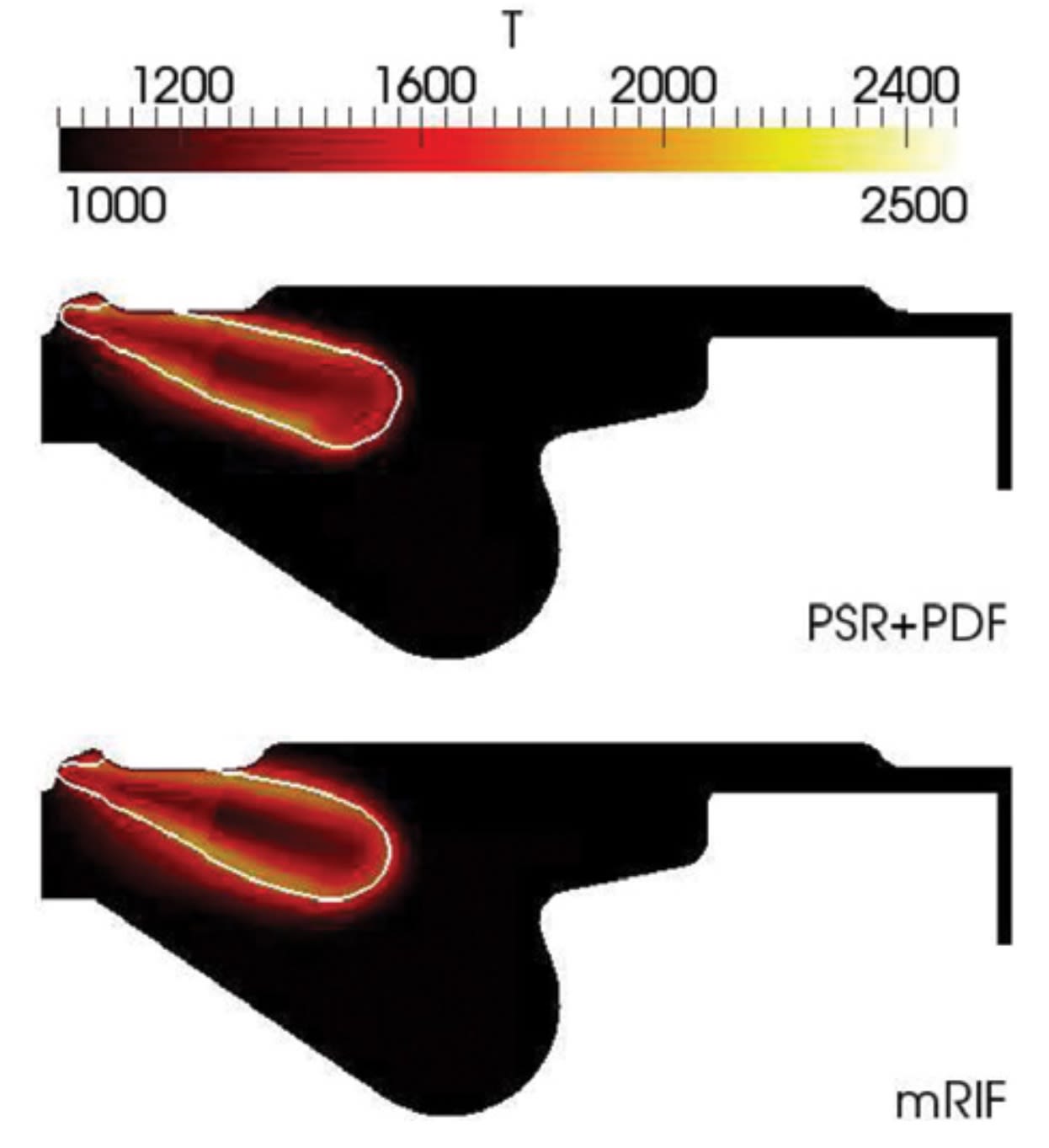

Predicted values of wall heat transfer were consistent with heat release rate profiles. Heat losses from the PSR+PDF model were higher due to the amount of energy that is released during the mixing-controlled combustion phase. MRIF results were satisfactory and in rather good agreement with experimental data, which were derived from a diagnostic experimental tool.

Data showed that it is possible that both models predicted a flame that stabilizes at the nozzle exit. This might happen for two different reasons. First ambient density is very high (~30 kg/m3 and there is no EGR) and expected lift-off length is very low since it generally decreases with both ambient density and oxygen concentration growth.

Furthermore, the mesh structure is not completely spray-oriented in the nozzle region and this affects computed distributions of mixture fraction variance and scalar dissipation rate, which are probably lower than what should be expected.

For this reason, the MRIF model does not extinguish the flame and also mixture fraction variance does not play a significant role in the progress variable reaction rate. Simulations with a spray-oriented mesh will be carried out in a future work. Computed flame shapes by both models are not very different during the initial ramp and this is in agreement with their similarities in terms of heat release rate.

Since both simulations were identical except for the combustion models, it was possible to see that the flame computed by the PSR+PDF model had a higher penetration since it has already touched the cylinder head and completely crossed the circular part of the piston bowl. This is mainly due to its higher reactivity compared to the MRIF. In-cylinder temperature distribution also explains why the PSR+PDF model predicted higher heat losses compared to MRIF: there is a larger area where hot gases are in contact with the cylinder walls.

Some considerations derived from the analysis of the A100 case apply for all the other operating points. In particular, computed pressure trace by the MRIF model is always higher than the one from the PSR+PDF approach. In all these five operating conditions, both combustion models match experimental data rather well with MRIF having the best performance on A75 and B50 (both partial load) conditions in terms of predicted maximum cylinder pressure and PSR+PDF in the other two cases.

In all the operating conditions, including C100 (partial load) and Cruise (constant speed), the initial part of the main combustion process is always better predicted by the PSR+PDF model, which better incorporates effects of local flow during ignition, where not only mixture fraction but also distribution of combustion progress variable affects heat release rate.

To improve MRIF model results in the first part of the combustion process, probably more flamelets need to be included and this could allow to account better for the local distribution of the scalar dissipation rate in the domain.

However, the MRIF model performs better in the second part of the main combustion process where the main pollutants are formed. This happens either when the HRR remains constant for a while or at low load conditions where it suddenly decreases since a small amount of fuel is injected, as for the operating point B50 or Cruise.

In operating points where pilot injections are used (A75, B50, and Cruise), both models perform almost in the same way: this is because fuel generally ignites in regions where mixture is almost homogeneous and the scalar dissipation rate from pilot injections is very small. However, agreement between computed and experimental data of HRR for pilot injections needs to be improved, but this is probably more related to spray modeling rather than combustion.

In particular, more detailed investigations will be performed about the measurement accuracy of injected fuel flow during the pilot events and hole-to-hole or shot-to-shot variation to assess the effect on the simulation results.

Finally, in terms of computational time, use of tabulated chemistry and already integrated PDF makes the PSR+PDF much faster than the MRIF model by a factor of 30.

To conclude the investigation and understand the capabilities of the proposed approaches to predict engine performance, the researchers compared computed and experimental values of the gross mean effective pressure (GMEP) for the five tested operating conditions. The GMEP was computed as the ratio between the gross indicated work and the cylinder displaced volume.

Such a parameter was chosen since all the simulations were limited to compression, combustion, and expansion phases with closed valves. Both approaches properly predict the GMEP with a reasonable accuracy, with the PSR+PDF model having the best agreement with experimental data mainly because of its capability to better reproduce the first part of the combustion process while the overestimation of heat release rate from the MRIF model in that phase is responsible for an increase of compression work.

Wrap-up

The two presented models were different not only in terms of flame structure assumption, but also in the way chemistry is handled. Chemical reactions are directly integrated by the MRIF model, this being an important computational overhead, while in the PSR+PDF model chemistry is tabulated and reaction rates retrieved as a function of mixture fraction and progress variables.

When tested at constant-volume conditions, both models showed the capability to predict auto-ignition and flame stabilization with the PSR+PDF one having the better performance since it accounts for progress variable distribution in the CFD domain. On the other hand, in the MRIF model everything is governed by the underlying assumption of being mainly a non-premixed combustion type.

Further investigation is required for the PSR+PDF model, for example on the effect of progress variable definition, to understand the discrepancy of the predicted cool flame behavior or the over-prediction of heat release rate.

When the same models were tested on the engine (same code, mesh, etc.) encouraging results were achieved: both models, without any tuning, were able to reproduce experimental in-cylinder pressure profiles rather well.

The initial part of the combustion process is better predicted by the PSR+PDF model, which includes not only the effects of mixture fraction but also of progress variable and local flow on combustion. During the mixing controlled combustion part, MRIF performed better since the flame propagates mainly in a diffusive way. This latter issue might be relevant for the prediction of pollutant emissions.

Once the chemical table had been created, the PSR+PDF model performed much faster than MRIF, which solved the chemistry on the fly. Bridging the gap between the two combustion models will be the main objective of a future work related to this research.

This article is based on SAE International technical paper 2015-01-0375 by Gianluca D’Errico and Tommaso Lucchini, Politecnico di Milano; Gilles Hardy, FPT Motorenforschung AG; and Ferry Tap and Giel Ramaekers, Dacolt International.

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance