Waste Heat Recovery for the Long Haul

A WHR system based on an organic Rankine cycle has been developed for a long-haul Iveco Stralis truck.

The FPT Industrial range of engines currently achieves a brake thermal efficiency (BTE) of approximately 46%, which is higher than comparable engines on the market today. However, through a series of detailed updates and continuous innovation, the aim is to improve this well beyond 50% by 2020.

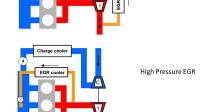

Alongside various technologies, waste heat recovered from exhaust by means of an Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) will play a significant role to reach this ambitious target. Simulations suggest that by tapping multiple heat sources, up to 5% improvement in engine efficiency is possible. A simplified system harvesting heat from only EGR and exhaust gas will allow up to a 2.5% increase of BTE.

As a proof-of-concept, AVL and FPT Industrial launched a joint project with the aim to develop a cost-effective mechanical waste heat recovery (WHR) system for an Iveco Stralis Euro VI truck.

Project targets were to demonstrate: the performance of the WHR technology, an ROI (end-user price) of ≤2 years, a vehicle fuel-consumption reduction of ≥3%, and an integrated system into the engine/vehicle, packaged on the Stralis.

At the beginning of the project, a thorough assessment of the most appropriate fluids, architecture, and available sub-component technologies was carried out.

Technology assessment

The study was initiated with thermodynamic ORC calculations for ethanol, water, and R245fa in view of the operating fluid selection. The boundary conditions for the cycle calculation were chosen based on realistic conditions for a real-world cycle of a long-haul truck in Europe.

The temperature of the hot reservoir (exhaust gas) was set to 348°C and the cold reservoir (cooling water) was set to 70°C in the calculation. Results of the ORC cycle calculations reveal that ethanol has the highest power output compared to water and R245fa, but also the highest condenser cooling power needed. Water has a considerable lower power output, but with a slightly higher ORC efficiency. The major advantage of water is the low condensing cooling power requirement.

Based on the temperature levels available in the long-haul truck application, ethanol is considered as the best choice due to the highest power output enabling the highest overall efficiency of the complete combustion engine and WHR system.

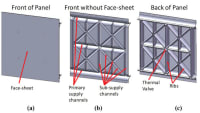

For system architecture, investigations showed advantages for a parallel compared to an in-series exhaust and EGR heat exchanger setup, enabling highest waste heat into the system with lowest complexity for the given temperature levels. The researchers rated system performance, safety, complexity, maturity, cost, and package-ability when determining the architecture.

The main challenge for the choice of components is the lack of standards for the WHR technology within the commercial-vehicle industry. Component suppliers are currently still struggling with the diverse market situation referring to the selection of operating fluid, safety standards, and the exact lifetime requirements for the individual components. After the definition of the fluid and the base architecture, an assessment of available prototype components was carried out (supported by steady state simulations).

Simulation and experimental tests were used to dimension the components. The system was then designed and virtually integrated on an Iveco Stralis Euro VI vehicle. The expander machine is mounted on the engine and the torque is mechanically transferred to the engine PTO via a belt drive and an intermediate shaft. The condenser is put on the truck frame side. Main components like exhaust evaporator (+ bypass valve), high-pressure feed pump, and reservoir tank (+ reservoir pressure control valve) are located in a compact box (WHR box) placed directly after the exhaust aftertreatment system.

Simulation activities

The steady-state simulation tasks were started with ORC simulations using ethanol, first without detailed component input from the suppliers. The target of these simulations was a parameter identification study where the influence of each individual parameter was analyzed. This information was useful for the later supplier discussions leading to the choice of the best available components for our specific concept. All simulations were performed with temperature and pressure dependent properties of ethanol for each calculation step.

The parameter identification showed that of the 14 WHR parameters chosen, the heat source enthalpy (temperature and mass flow) and the expander isentropic efficiency have the highest influence on the WHR power output. Additionally, the parameter identification showed only linear dependence between the WHR power output and the 14 parameters indicating less challenges with regard to complete system control and optimization.

After the initial supplier discussions, the steady-state simulations were extended with detailed component characterization input from the suppliers. A comparison was made between steady-state simulation and testbed measurement at A25, A50, and A93. Two approaches were used for the simulations: Prediction — only measured engine exhaust data taken for WHR simulation input, all other input data from supplier maps (expander, heat exchanger); and Recalculation — measured engine exhaust data and measured expander intake pressure taken for WHR simulation input, all other input data from supplier maps (expander, heat exchanger).

Good correlations between measurement and simulations were shown for temperature and pressure. For expander power and WHR B-Efficiency, the recalculation and measurement were slightly lower especially at operating point A93. The main reason for the differences are the slightly lower expander efficiency for the measurements compared to the supplier maps at this specific load point.

For proper prediction of fuel economy under real-life driving conditions all interdependencies and interactions between vehicle subsystems had to be taken into consideration — i.e., all transient energy fluxes (mechanical, thermal, hydraulic, electrical) have to be simulated.

Therefore, a complete vehicle system model consisting of engine model, powertrain model, and simplified control logic for the auxiliaries was built within a vehicle modeling environment. A thermal model of the engine structure, cooling system, and lubrication system was created in Mentor Graphics’ Flowmaster to appropriately simulate the engine transient thermal response of the engine. A thermal model of the exhaust aftertreatment system was set up to calculate the waste energy available for the ORC.

A transient simulation model for the WHR system was set up in MathWorks’ Smiling by combining steady-state performance data and transient response of components provided by the hardware suppliers. A semi-physical approach was adopted to keep the computational effort of multi-phase simulation within the requirement of long cycle simulations.

Each system is coupled over energy flows across system boundaries and run in co-simulation.

The vehicle model was validated with wind tunnel measurements performed at Mahle test facilities. Good agreement of both cooling system and exhaust system was achieved, with deviations mainly caused by small differences in the control strategy of cooling auxiliaries and necessary simplifications introduced in engine thermodynamic and exhaust aftertreatment modeling.

The validated model is used for fuel economy simulation on real-life cycle, as plant model for the development and optimization of WHR control software functionalities, and for hardware sensitivity investigation. Non-trivial dependencies such as interaction between WHR power generation and parasitic loss of auxiliaries can be evaluated and an optimal trade-off is determined. The simulation results contribute to the definition of requirements for each of the WHR components.

The current status of the transient simulation results predict slightly less than 3% fuel-consumption reduction for the Stralis Euro VI truck during the real-world driving reference cycle utilizing waste heat from both the EGR and exhaust evaporator. However, the transient simulation also shows a potential of increasing the fuel-consumption reduction to around 3.5% by applying further realistic cost-effective measures such as efficiency improvement of the ethanol pump and expander, vehicle cooling system and fan control strategy improvements, a separate 60°C cooling system for the WHR condenser, as well as enabling under-pressure conditions. Performing the calculation with a typical U.S. real world transient cycle results in up to 5% fuel-consumption reduction due to the higher load profile in the U.S. compared to Europe.

Testing activities

Three major test series were planned in the overall project: stationary testbed testing (detailed here), transient testbed testing, and vehicle testing on road.

For the stationary test bed setup, an FPT Cursor 11 Euro VI engine (including exhaust aftertreatment system), WHR components, and required measurement equipment were all integrated to an Iveco Stralis vehicle frame and put on a testbed pallet system. Using this approach, very similar component packaging can be achieved compared to the demo truck, leading to similar system behavior of e.g. thermal inertia, heat losses, or pressure drops.

The positive effect of the WHR system on fuel consumption is evaluated by means of the engine torque measured on the engine dyno and precise fuel-consumption measurement. Optionally, the expander torque is also measured using a strain gauge-based system.

The stationary testbed testing was split into the following work packages: engine start-up and initial WHR system operation; WHR control system application; parameter variation and mapping; component characterization; mechanical development and safety; and fuel-economy measurements and influence on overall performance and emissions.

The testing activities were performed in close interaction with simulation, thereby enabling the optimum operation of the WHR system with the given boundary conditions.

Stationary measurements at 1200 rpm (A-speed) with exhaust as the only heat source confirmed the simulated fuel-consumption reduction of more than 5 g/kW·h.

The fuel-consumption reductions with the WHR system were achieved without any significant changes to the emission or performance of the combustion engine. This is due to the closed-loop air path control together with the fact that the increased backpressure of the exhaust evaporator (<30 mbar) is well within the range of the backpressure differences experienced during the loading of the diesel particulate filter (DPF).

ROI and outlook

With the prototype system, the ROI target of ≤2 years can be met considering only direct material cost. Until start of mass production of the WHR system, however, further cost-reduction effort is required to allow for sufficient cost margin. This depends very much on the final economies of scales for WHR components.

First results from bench testing indicate a final fuel-economy gain around 3.5% for the Stralis Euro VI truck during the real-world driving reference cycle utilizing waste heat from both the EGR and exhaust evaporator.

At the time of this paper’s publication, transient testbed tests will be performed at AVL continued by vehicle tests under real-life driving conditions at CNH Industrial by end of 2015.

The authors thank all of their partners and suppliers in the project (Amovis, Mahle-Behr, Norgren, Magna).

This feature is based on technical paper ICPC 2015 - 5.1 written by P. Krähenbühl and F.Cococcetta of FPT Motorenforschung AG; I. Calaon of Iveco; and G. Gradwohl, M. Tizianel, M. Glensvig, and H. Schreier of AVL List GmbH. Copyright © 2015 AVL List GmbH, CNH Industrial N.V., and SAE International.

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance