Machine Learning Drives Design Space Exploration

By combining simulation with probabilistic ML, engineers can chart the full design landscape, quantify uncertainty and uncover viable options that intuition and brute force alone would miss.

Components and systems are routinely designed and validated virtually through tools like CFD and FEA before any physical prototype is built. The benefits are obvious: faster iteration, reduced cost and better products.

But simulation is not cheap. Each run can take hours, consume costly GPU/CPU resources and require highly skilled engineers who are already in short supply. Licenses and compute costs can easily reach tens of thousands of dollars per seat, and most teams can complete only a few runs per day.

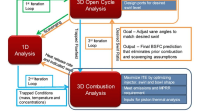

This bottleneck becomes especially challenging in high-dimensional engineering problems. For example, simulating combustion inside a diesel engine requires modeling the complex motion of the valves and the piston, along with 3D multi-physics variations over time. Key variables include injection timing, pressure and quantity (for pre-, main- and post-injection); spray angle; EGR (exhaust gas recirculation); piston bowl geometry; valve timing; compression ratio; and swirl characteristics, spray interaction and combustion – the list goes on.

Even the most experienced performance engineers struggle to reason through the interactions of more than seven variables at once in a known system. Outside of familiar parameter ranges, intuition alone has limits. Yet vehicle manufacturers are trying to work on problems with 30 or more dimensions.

This is no failure of engineering talent. In fact, much of technical and business education relies on reducing problems to two or three dimensions to make them manageable for the human brain. But this simplification has a cost. Opportunities for innovation can be missed. Entire regions of the design space – potentially rich in viable or even optimal solutions – remain unexplored.

Specialized ML vs. general-purpose AI

Recent interest in artificial intelligence, particularly in large language models, has brought a mix of optimism and concern across many professions, including engineering. A recurring question is whether AI tools could displace skilled roles. In the context of engineering design and simulation, this concern is often misplaced.

The machine-learning engineering tools being developed by Secondmind are fundamentally different from general-purpose generative AI. They are not based on large language models. Instead, they rely on a system, Secondmind Active Learning, that incorporates a branch of probabilistic machine learning rooted in Gaussian processes and Bayesian Optimization – methodologies well-suited to problems where data is limited and expensive to obtain. The scientific foundations were laid down by Professor Carl Rasmussen at the University of Cambridge, whose research remains highly influential in this area.

The goal is not to replace engineers, but to enable more thorough understanding of the design space than would otherwise be possible under licensing or compute cost constraints. It gives engineers a way to see further and work smarter with the tools they already have. By highlighting where to focus scarce simulation effort, machine learning helps them uncover patterns and solutions that would otherwise stay hidden in the noise of high-dimensional problems.

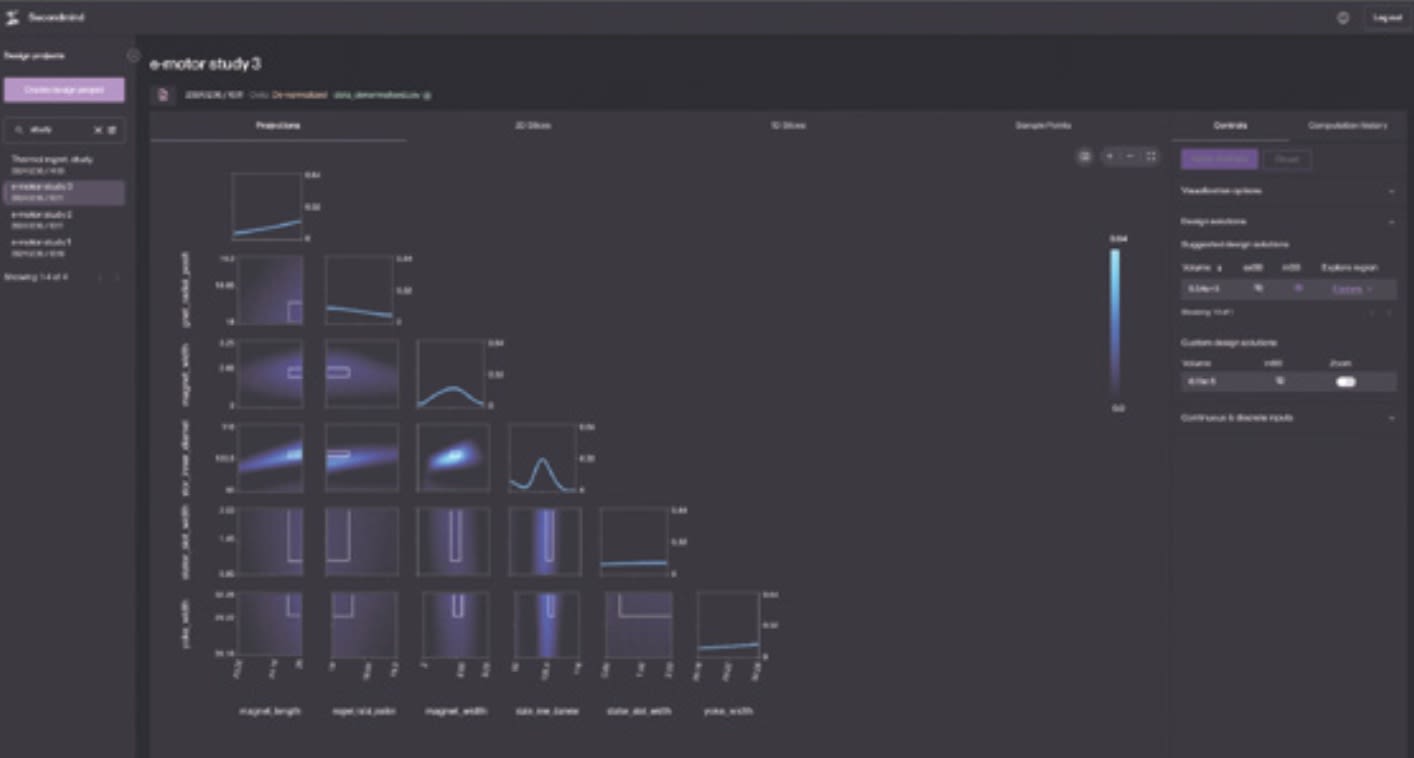

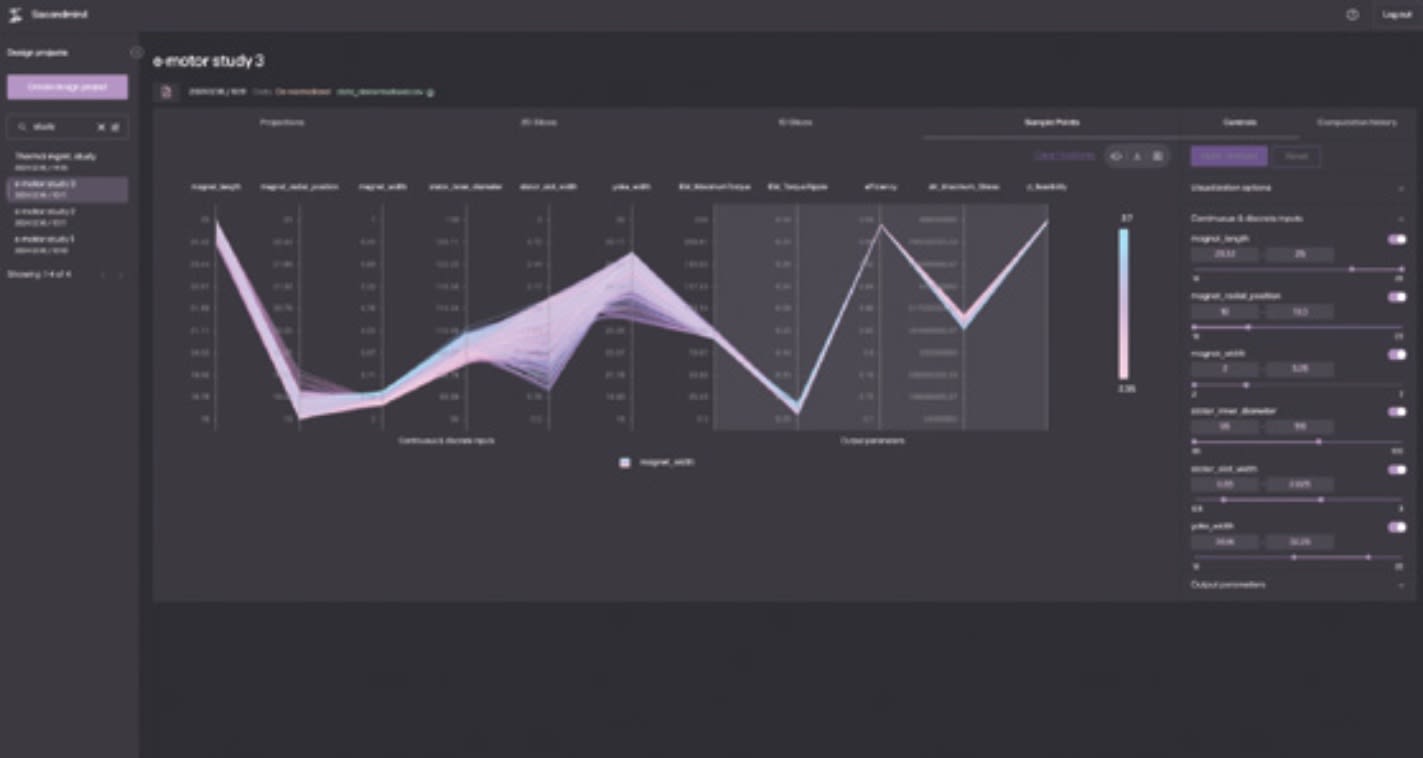

In practice, this means the engineer spends less time grinding through routine runs, and more time making the kinds of design decisions that move a program forward. Working Secondmind enables the identification of all the feasible designs that meet the engineer's requirements, while the engineer uses the intuitive visualization tools, applying their judgement, domain knowledge, and creativity to choose the best path.

Defining the feasible solution space

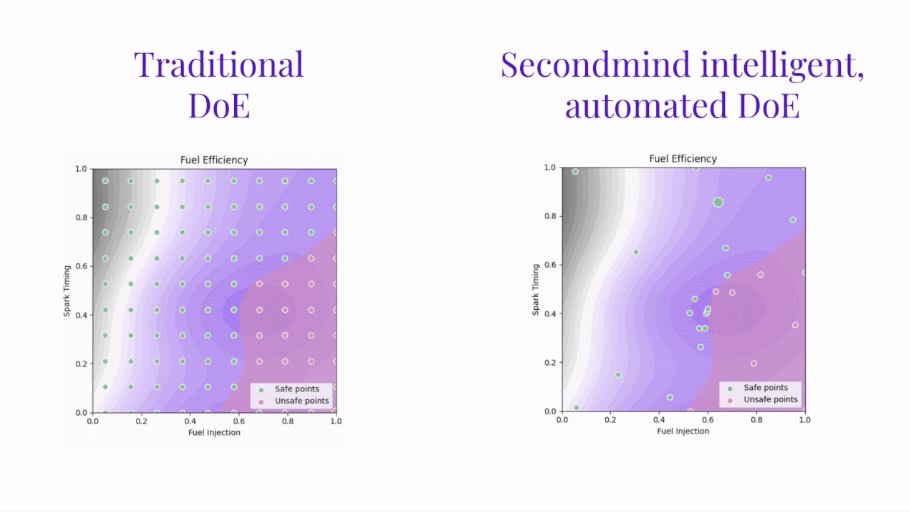

What does this human-machine partnership look like in practice? One clear shift is in how engineers frame the problem. Traditional workflows encourage a point-based mindset: identify a handful of candidate designs, simulate them, and hope that one comes close enough. But with dozens of interacting variables, this approach often narrows the field too early.

Probabilistic ML changes the game by allowing engineers to model the entire feasible region. Instead of asking “which design point is best?”, engineers can ask “what does the full landscape of viable options look like?” so they can apply a set-based design methodology. Engineers can now discover multiple promising solutions – and understand the trade-offs between them.

By quantifying uncertainty, engineers also gain an honest appraisal of what they don’t yet know – something that traditional simulation workflows tend to obscure. This awareness leads to more robust designs and fewer surprises when hardware is eventually built.

The economics of fewer, smarter simulations

Every engineering leader has felt the pinch of simulation budgets. The fully absorbed cost of a single CFD or FEA run may be hundreds of dollars.

The intuitive response is to push for more efficiency – streamline end-to-end workflows, optimize solvers, reduce mesh density, trim runtimes. These measures help, but they don’t break the bottleneck. The real lever is choosing the right simulations to run in the first place.

Probabilistic ML does precisely that. By using active learning, it identifies where the uncertainty in the design space is greatest and selects new simulations that will add the most relevant information. Instead of 2,000 brute-force runs, a team might need only 400 carefully targeted ones and yet gain better insights.

The economics are compelling. Fewer runs mean lower compute bills and reduced licensing needs. But there’s also a human dividend. Engineers spend less time setting up and post-processing repetitive runs, and more time on creative, higher-value activities such as interpreting results, proposing novel geometries, and guiding program decisions.

The time saved translates directly into faster development cycles. Compressing simulation workloads can bring forward physical prototype builds or eliminate one iteration entirely. A more thorough understanding of the design space also helps different teams, working on different aspects of a design, to collaborate more effectively.

Design space exploration vs. calibration

The “curse of dimensionality” is not confined to one corner of the vehicle development workflow. It appears both in system design and in calibration, albeit wearing different masks.

In calibration, engineers work within a defined system – say, a low-emissions diesel engine. Their task is to create control maps that give optimum torque and fuel consumption performance. Here, high dimensionality arises from the sheer number of interacting control parameters. To test every permutation of the many different variables over the entire operating speed range could take months of test cell time and burn thousands of liters of reference fuel.

The underlying difficulty is the same in both design and calibration: too many variables and limited time and budgets to test every permutation of variables. Intuition helps within familiar domains, but falters when engineers push into new architectures, unfamiliar fuels or novel materials. The same probabilistic ML approach becomes valuable in both contexts.

Integration into existing workflows

A common fear when new engineering software is proposed is that it will require abandoning established toolchains and proven processes. Engineers have invested years in mastering and benchmarking CFD, FEA, 1D modelling environments, and bespoke in-house codes. Methods teams have built scripts, libraries, and workflows that orchestrate these tools to provide results that they can have confidence in. Nobody wants to throw that away.

The reality is that ML-driven design space exploration does not replace these tools. It sits above them, orchestrating their use more intelligently. The integration principles are straightforward:

- Inputs are tool-agnostic. If variables are defined consistently, the ML layer can absorb results from any solver or test rig without having to go through a rigorous and time-consuming re-evaluation required for new tools.

- Workflows remain iterative. Instead of launching 500 runs in one batch, engineers launch smaller, targeted batches. The ML model intelligently and automatically updates after each wave, pointing the way to the next.

- Engineers remain firmly in the loop. The software suggests, but humans decide.

This architecture reassures methods teams, because it preserves their hard-won toolchains while making them more productive. It also reassures simulation engineers, because it elevates their role. Rather than being “simulation jockeys” pushing buttons, they become explorers of a vast design space, supported by a guide that points out where the most interesting regions lie and where uncertainty is highest.

Over time, organizations that adopt this approach see a subtle but important cultural shift. Simulation is no longer seen as a bottleneck, but as a strategic enabler.

Case example: exploring cooling strategies

Consider a battery pack thermal-management project. The design team must ensure that every cell stays within a tight temperature range under a wide variety of load and ambient conditions. Traditional simulation might involve evaluating dozens of liquid cooling plate geometries, routing options and pump specifications. Even with parameter reduction, the combinations can number in the thousands.

The brute-force approach is impractical. Engineers would need to pick a handful of candidate designs and hope their intuition guided them towards viable options. Inevitably, many potentially strong designs would remain unexplored.

The Secondmind Active Learning approach works differently. After an initial set of simulations, the ML model identifies where its predictions are most uncertain. It may, for example, be confident about performance in mild climates but uncertain about behavior in cold-weather extremes. The next batch of simulations targets those weak spots.

With each cycle, the model’s understanding of the design space improves. Engineers can visualize not just which designs pass or fail, but the shape of the feasible region as a whole. Multiple cooling strategies emerge, each with quantified trade-offs in cost, weight, and performance.

The benefit is not just efficiency – although fewer simulations are run. The greater value is confidence. When the time comes to build a prototype, the team knows they have explored the design space thoroughly, not just skirted its edges.

From intuition to quantification

Engineering has always relied on expert intuition. The ability of experienced engineers to “feel” which parameters matter most is hard-earned and invaluable. But as systems grow more complex, intuition alone is no longer enough. The interactions between dozens of variables exceed human capacity to reason unaided.

Probabilistic ML does not replace intuition, it extends it. Where intuition is strongest, the model can confirm and quantify. Where intuition is uncertain, the model can highlight risks or opportunities. The net effect is a cultural shift from arguments based on gut feel to discussions grounded in quantified evidence.

This shift reshapes internal dialogues. Simulation and test teams align better on which prototypes to build. Engineering and product management can frame trade-offs with clear visualizations of cost, weight and performance regions, reducing conflict and accelerating agreement.

The importance of this cultural transition is also being recognized beyond individual companies. Initiatives such as the NAFEMS (National Agency for Finite Element Methods and Standards) ASSESS are driving collective thinking on how simulation, data and machine learning can transform engineering practice.

Looking ahead

The trajectory is clear: vehicle engineering problems are not getting simpler. Meeting Euro 7 emissions, designing for hydrogen combustion, optimizing EV range and charging behavior – each raises the dimensionality bar higher.

General-purpose AI won’t solve this. What’s needed is engineering-grade machine learning: methods that respect the scarcity and cost of simulation data, integrate with existing workflows, use existing validated and proven simulation capabilities and provide clear, explainable guidance.

Simulation-first design transformed engineering once. The next transformation is simulation-with-ML – a design paradigm that enables engineers to explore broadly, decide confidently and innovate faster.

For those ready to adopt it, the reward goes beyond lower costs or faster cycles. It’s the ability to manage complexity at a scale where competitors stall – turning simulation from a constraint into a competitive advantage.

Nick Appleyard is vice president of sales and business development, Secondmind, and wrote this article for SAE Media.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsAutomotive

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

ArticlesAR/AI

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

Road ReadyDesign

Webcasts

Semiconductors & ICs

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Power

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

AR/AI

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility