Virtual Casting Improves Powertrain Design

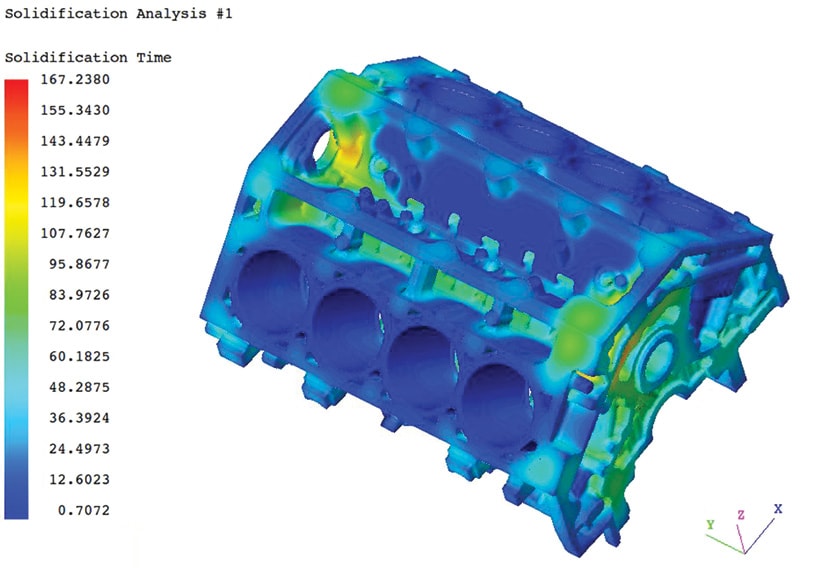

As designers continue to look for ways to cut weight and increase performance, casting simulations are helping optimize designs through faster, more accurate predictions of the casting process used to create key components.

CAE (computer-aided engineering) is proving to be a vital part of the engineering process in casting. “We would not contemplate making even a simple casting today without first analyzing it using simulation,” explained Ted Kahaian. Prototype Engineering Manager of Tooling and Equipment International (TEI). The company specializes in prototype casting as well as supplying tooling for high-volume production. CAE as a tool is helping meet the challenge of taking weight out of parts such as engine blocks and heads as well as other powertrain parts.

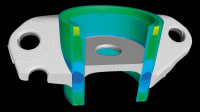

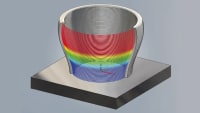

To help design castings for lighter, ever more complex parts, TEI is turning to CAE for more accurate prediction in their design-for-manufacturing process. Visualizing data is a unique capability over physical prototypes. There is only so much data and design direction an engineer can get from a physical test of a casting. Simulation allows an operator to see temperature profiles and histories, fill velocities, solid fractions, and solidification rates at any point in the part.

Visualizing results is one thing, trusting that the data composing those visualizations is another. Can they trust the data they are seeing? Kahaian says yes. Correlation and validation with measurements from physical tests — along with comparisons to other simulations — gives TEI confidence in the results.

Nevertheless, building some physical prototypes is still necessary. What has evolved is an iterative process between simulation and building physical prototypes for a final design. However, each year TEI is accomplishing more with simulation. “Just two or three years ago, I would say we could accomplish 70% of the final design with simulation alone,” explained Kahaian. “Today, in 2015, that is closer to 90%.”

Enablers for adopting simulation as core competence

In fact, casting simulation is becoming so integral to its work that TEI stopped contracting out simulation work and brought it in-house. A number of trends facilitated this. Universal use made it easier to amortize the cost of owning the capability. Computers themselves are now powerful and cheap. So, TEI easily affords performing complex fluid dynamics as well as solidification, and analysis.

“We can buy some computers from our local mall and run our models without much trouble,” reports Kahaian, “We do not need high-performance computing clusters.” While some complicated models may take several days of clock-time to compute, he reports that 85% of their simulations are done in less than a day.

Perhaps the most important trend is the ease of use. “You do not need an engineering degree to run this software,” said Kahaian, explaining that only basic computer competency and knowledge of casting processes are needed. Knowing how to make a consistent mesh, choosing a stable time-step, understanding order of error in the discretization, and other arcane ‘computational engineering’ language is not needed, he said. “If an operator can import a geometry file, within a matter of minutes the software will generate a compatible mesh and within a few hours you can be watching your casting in a simulation loop and see how your casting will fill and solidify,” Kahaian said.

Improving CAE software to make it even easier to use remains a major challenge, according to Ken Siersma of EKK, makers of EKKcapcast, the software TEI uses. At this stage, the challenge is in the process itself rather than interfaces with the computational methods. A complete casting simulation follows a defined process. First, users create a computational mesh from data derived from a CAD (computer-aided design) file. Then, they attach specifications of material properties and define initial conditions to simulate the flow of molten metal into the casting or tool. After that, the software predicts solidification.

“There has, however, been a bit of a steep learning curve with the software, so in recent years we’ve been focusing on making it easier to use,” said Siersma. EKK recognizes that its typical customer might not be a trained ‘computational engineer.’ The result of their work so far? “[Our users need only] a good background in castings and an interest in using simulation software,” he said. “We can teach the user how to use the software, but we can’t teach the user how to make castings.” Users also need some experience in using CAD software. He reports future improvements will include tighter integration between the different modalities, making the simulation data move easily from fluid prediction to heat-induced stress analysis.

Powertrain castings unique?

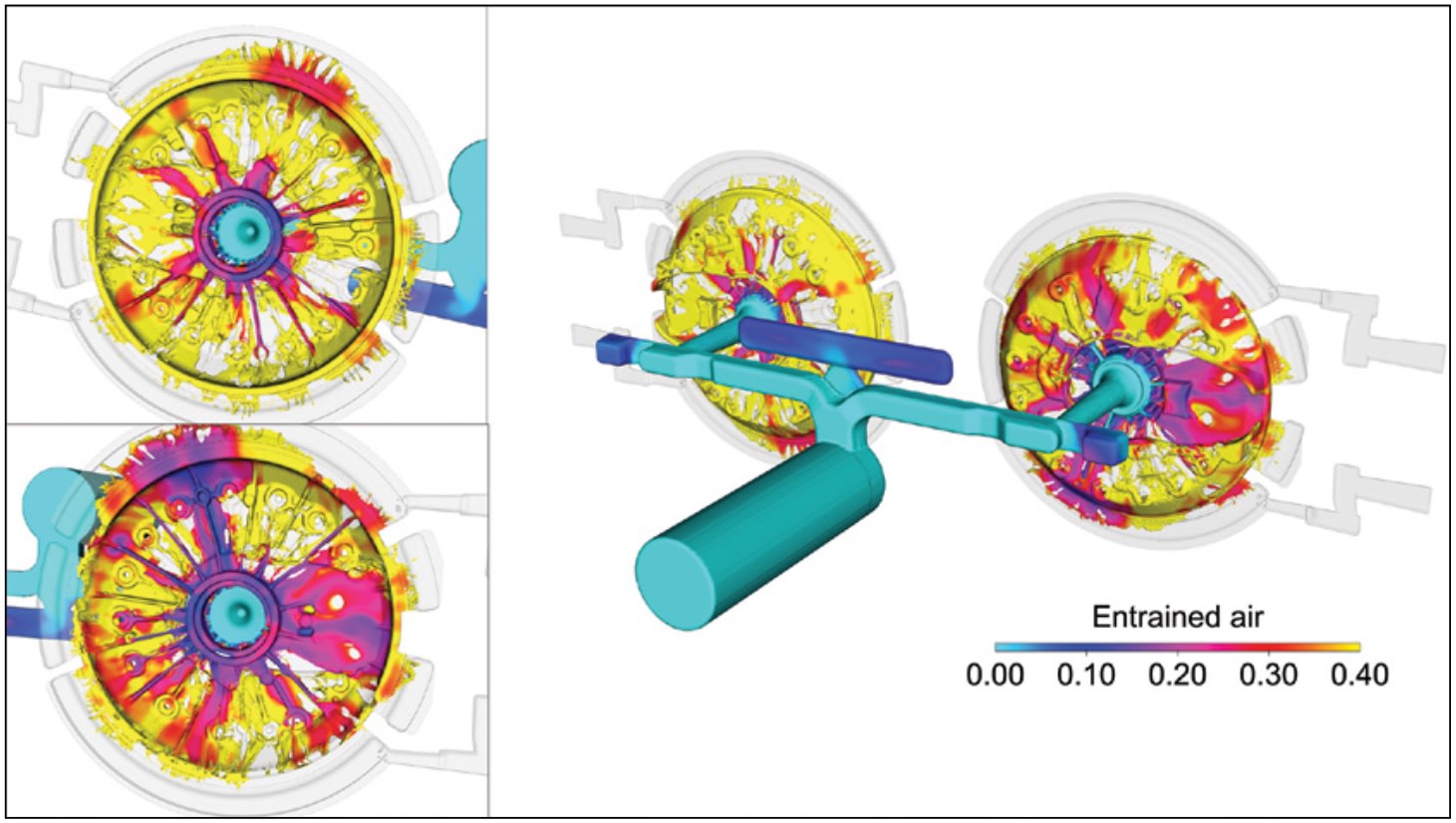

Siersma notes that powertrain parts have many of the same problems as any other casting. “Porosity is perhaps the biggest issue in castings,” he explained. Engineers evaluate the simulated casting solidification pattern and tweak it so that the last place to solidify is either not in the casting or in a low stress area of the casting. One issue to look for is shrink porosity as the casting solidifies. These voids occur in the last place it solidifies if it is inside the casting. Filling porosity is also important, with trapped air or bad filling patterns in the gating leaving voids. Sometimes those two problems can work together to make the problem worse.

“You also have filling-related issues such as oxide formation and early solidification, along with warping of parts and stresses that develop as a part cools,” explained David Souders VP Sales, Support & Marketing of Flow Science, the provider of the FLOW-3D CFD software that includes a casting module. “With powertrain components, of course, you’re dealing with parts that are under a lot of stress and in a difficult environment. Making the parts durable and defect-free is, perhaps, more critical than with many other parts in an automobile.”

“Today’s [powertrain] designs call for thin-walled castings, which are complex and computationally intensive to simulate,” he said. A fine mesh is required to resolve the thin walls, increasing the computational load. He also pointed out that casting simulations are ‘free surface’ problems, requiring computing the moving interface between a gas (air) and a liquid (molten metal), adding further computational complexity.

“We are addressing these issues by working to improve the speed of our solver and by offering customers the ability to move to high-performance computing (HPC),” Souders said. HPC offers customers the use of multiple compute nodes to share the work and provide results more quickly without losing the accuracy and reliability of a coarser computational mesh. “We are also constantly focused on the ease of use, both on the front end, making the setup process simple and intuitive, and the back end, enabling the extraction of key data and its presentation easier,” he said.

While offering an easy-to-use mode, their software also offers flexibility for knowledgeable power users. A number of parameters and the method used by the solver can both be tweaked. The user can select explicit computation for more accuracy or implicit computation for more speed, or a mix of both.

A faster computer is not enough, according to Dr. Konrad Weiss, founder and CEO of RWP, makers of WinCast expert. “You have to rewrite the algorithms to take advantage of these new computers with 64 bits and multiple cores,” he explained. He also noted that graphics cards have much faster calculation speeds than those of the general processor. “We use the GPUs for even faster computation and more accuracy.”

At the same time, he noted a limit as to how much accuracy is enough. “Within a degree centigrade is sufficient for most foundry applications,” he said, while WinCast expert provides precision within 0.001 of a degree centigrade.

Growth of capability, new applications

Weiss also sees variations in how people use the software. While most large automotive firms use it early in the design stage, small to medium companies continue to use it as a forensic tool when something goes wrong.

He feels that automotive powertrain parts present a unique challenge when it comes to NVH. “Powertrain parts are normally high strength, but they also need to be silent,” he said. “We combine casting simulation with acoustics” including combining frequencies modeled as eigenvectors (eigenfrequencies) with the mechanical properties predicted from casting to get the ideal part.

He also views material optimization as an important evolving use of casting simulation. “Saving even a small amount of weight is important and is becoming a key point for our customers who are suppliers,” he said. They find significant value in shaving 10 g (0.35 oz) off of a 6 kg (13 lb) part and use WinCast expert to develop new processes, achieving specific mechanical properties in specific areas of the casting.

“They use our software to try different approaches to get these specific mechanical properties, even developing new processes,” he explained. This includes applying different heat treatments post-casting as well as new ways of casting the part.

The future is more than technical, as he sees it. “While we can improve accuracy — and we must — we also need to worry about the total lifetime of a component,” he said. This means combining technical simulation with cost data to optimize the total value of a part. “A technically good part can be too expensive. We need to continue investigating the cause and mitigation of defects, but now we must combine the technical with cost to provide full optimization.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...