Steel Stands Tall

Mobility’s longtime incumbent material maintains its star status for vehicle structures through constant innovation—and a collaborative development model.

In 2014, just before Ford shook the industry with the introduction of its aluminum-intensive F-150, Ducker Worldwide released a study for the aluminum industry. The report predicted that the light metal would dominate the North American light-truck segment in the next new-model development cycle. Some seven out of ten pickups in the next round were going to be AL-intensive, the study opined. A tidal wave appeared to be building.

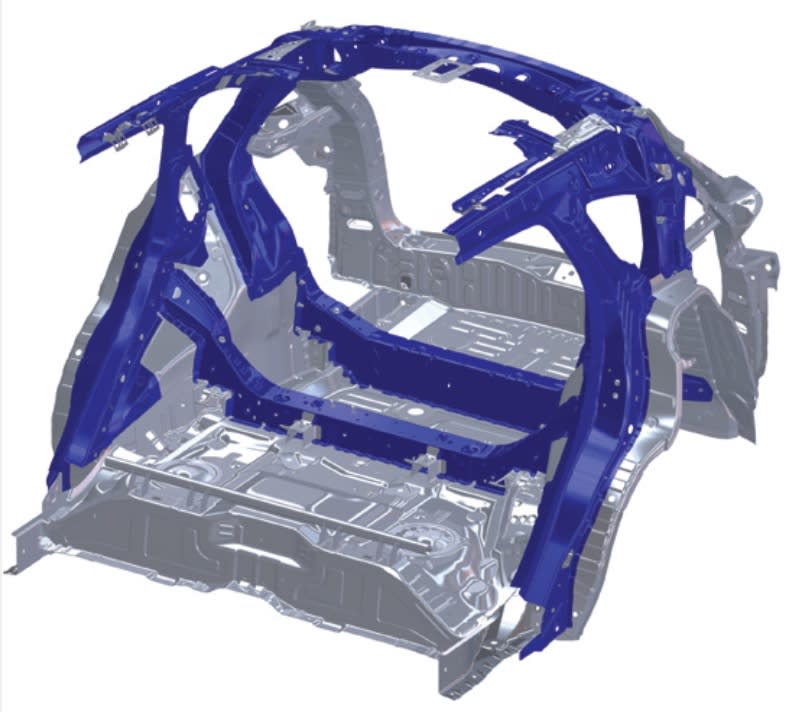

Five years later, not a single pickup has entered production with an AL-intensive cab and bed. While Ford changed over the body structures of its all-new 2018 large SUVs to aluminum, steel rules the midsized 2019 Ranger. In the enemy camps, the 2019 Chevrolet and GMC Silverado and Sierra 1500 and their brawnier HD cousins continue GM’s mixed-materials strategy for pickups and SUVs. FCA’s Ram and Jeep brands have stuck mainly with steel structures; the new JL-series Jeep Wrangler changed to aluminum doors (and hinges), hood, fenders and windshield frame, utilizing Alcoa’s new C6A1 high-form alloy and its 6022 and A951 alloys.

Also contributing to Wrangler’s shedding up to 200 lb (91 kg) is its magnesium rear swing gate—FCA’s reprise to the feathery (and not cheap) Mg lift gate used on the current Pacifica minivan. Underpinning each of these trucks are ladder frames representing the ultimate in finite-element-optimized high-strength steel, with a few AL crossmembers.

“We’ve migrated from the idea that we need a single-material-intensive vehicle” into an engineering mindset of “the right material, produced the right way and engineered into the right part of the vehicle,” observes Dr. Alan Taub, professor of Material Science & Engineering at the University of Michigan.

Case in point: Rivian’s pioneering R1T electric pickup slated for 2021 features a main cab structure tailored for reduced mass and crash safety using various high-strength-steel grades, with aluminum closures. Even the luxury carmakers are following suit. Tesla abandoned the AL-intensive route used on its Models S and X in planning its high-volume, lower-priced Model 3 and Model Y, both of which have significant steel content. Audi has switched from an AL-intensive strategy on its uni-bodies to the mixed-materials pathway (even for its new eTron electric vehicle) that is becoming universal across the industry.

“The environment around mass reduction has changed from aluminum-intensive to mixed materials—that’s certainly what automakers are telling us,” notes Dr. Jody Hall, VP of the automotive market for the Steel Market Development Institute. She and Dr. Taub believe steel’s inherent value compared to light metals and carbon composites, along with the steel industry’s aggressive development of new, stronger grades suitable for vehicle use will continue its reign as the “core” material for body structures and chassis systems — for the next decade at least.

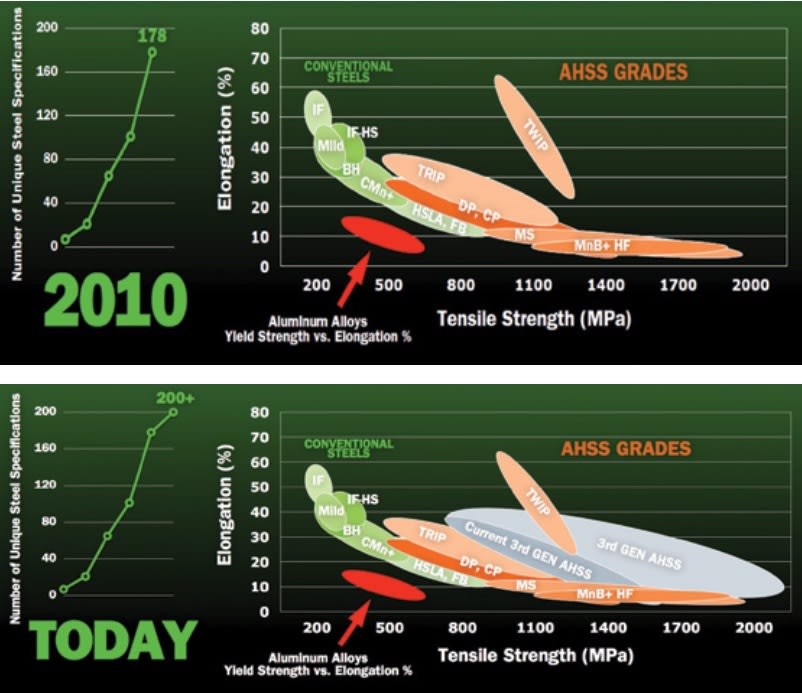

A look at the accompanying chart shows the growing number of steel grades based on their strength and elongation. Ranging from about 200 MPa to 2,000 MPa, the bandwidth is significantly wide for that of any single metal. “You’d have to use a reinforced composite to match steel’s strength range,” Dr. Hall asserted, “but the cost to achieve that changes to many times that of the base material. There’s no other material ‘system’ that delivers steel’s range of performance at such a high value.”

‘3rd-Gen’ material blitz

Steel’s appeal to development engineers has been the industry’s continuous innovation-by-collaboration model that began in the 1980s when steelmakers had to defend against a major assault on automotive skins by the plastics industry. “We work with them an industry instead of as individual steel companies,” Dr. Hall explained. “They show us their designs and we work with them to achieve them in a more cost-effective manner.

“That’s not saying individual steel companies don’t work with automakers on their needs, but when we do it as an industry, it’s really appreciated by the customers,” she said. “Because we’re all trying to do more with fewer resources. It’s a very efficient way of getting results, in terms of resources and timing. We’ve been working this way for decades and it continues to pay off.”

The most advanced high-strength (AHSS) and ultra-high-strength (UHSS) steel grades will offer 2,000 MPa tensile performance. The so-called “3rd Generation” AHSS was launched commercially in 2018, from major producers ArcelorMittal, AK Steel and Nucor. The products are a response to OEMs’ requests for more elongation/ductility for a given strength.

“Part of the reason for this request is they didn’t want to use as much press-hardened steel as they do now,” Dr. Hall explained. “They want to use their current infrastructure to stamp, at room temperature, the more complex geometries they couldn’t get with some of those AHSS. They’re looking at reducing cost in their stamping lines.”

Because of the lead times in validating any new material for automotive use, the roll-out of the 3rd-Generation grades will happen gradually through 2023, when the new grades will enter production vehicle programs in significant volume. Experts note that press-hardened steel will remain available because it enables body engineers to achieve complex geometries with high strength. Honda has engineered it into the A-pillar design of its NSX supercar, in order to minimize the pillars’ cross section and thus improve driver visibility, and uses 1,500-MPa grade for the inner and outer door rings of the RDX.

Aluminum alloys are lower in formability for the same strength levels; this hurts AL applications “because geometry adds a lot to the performance and can help with mass reduction — the more geometry you can get into a part enables thinner sections in many cases,” Dr. Hall said.

While many may think that future EVs, both autonomous and non-, will be constructed of aluminum and carbon fiber, steel has a major role to play in the propulsion revolution. In an EV, the actual impact of lightweighting actions is reduced compared with combustion-engine vehicles of comparable size.

“When you lightweight a conventional vehicle’s body and chassis components, which make up roughly half the vehicle’s mass, you achieve maybe a .2 mpg improvement; it’s incremental,” Dr. Hall explained. “If it’s a battery-electric vehicle, the improvement would be far less. The [body-structure weight-reduction] gains don’t justify the expense.” EV battery pack structures, however, are a major growth area for aluminum, Tier 1 suppliers tell AE.

“Everybody assumes that we’ve innovated as much as we can, because steel has been around in vehicles for well over 100 years,” Dr Hall quipped. Automotive body structure engineers know how wrong that assumption is.

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance