No Hands, Lots of Brains

A hefty amount of computing power built with new hardware and software architectures will be needed when vehicles begin taking over more of the driving tasks.

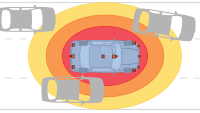

Autonomous vehicles have garnered much attention in recent months, but many technical hurdles face developers tasked with giving drivers more freedom to do other tasks. Engineers need to develop hardware and software strategies that let electronic control units synthesize and analyze data from multiple sensors quickly, then control actuators that let vehicles avoid accidents.

Many of the sensors needed for increased levels of autonomy are already in use today. But combining all the inputs from adaptive cruise control, lane departure warning, and other systems, then analyzing data in a foolproof manner, is a complex task.

Reliability, redundancy, and testing are critical obstacles to be overcome before vehicles pilot themselves. ECUs are among the many elements that must be enriched for vehicles to start becoming autonomous.

“Several technologies will need enhancements: artificial intelligence, better multi-spectral sensors, sensor fusion, and better fault tolerance including sensor and actuator redundancy,” said Brian Daugherty, Visteon’s Associate Director of Advanced Development and Intellectual Property. “Other areas include vehicle trajectory models, image recognition, system integrity, and fail-safe strategies.”

All these improvements come with a price tag. Another big challenge is to provide autonomous driving functions at an affordable system cost. Planes and trains already operate autonomously, but their cost structure is dramatically different.

“An airliner’s autopilot equipment costs more than an entire luxury car,” said Bill Riedel, Automotive Director at Analog Devices. “Yet the plane’s task is quite simple compared to what autonomous cars need to do. Airliners operate under strictly controlled conditions, not in close proximity to dozens of other moving objects, pedestrians, or distracted operators.”

Taking control

Making today’s stand-alone systems work in harmony will take a lot of computing power. Multiple inputs will have to be compared before the system can make any decisions on braking or steering. Many developers plan to perform these functions in a powerful central controller.

“There’s a trend to offload intelligence from the sensor, moving to a centralized architecture,” said Andy Whydell, Product Planning Manager at TRW Electronics. “That means sending more data to the central CPU, where fusion is done with more data so you get the most robust understanding.”

It will take a lot of computing power to collect and analyze incoming data and tell braking or steering systems how to respond. It’s difficult to get enough computing power in automotive-grade microcontrollers without creating a large, complex ECU. Engineers are examining different strategies for centralized and distributed architectures.

“A lot has to happen in the central controller; we’re going to need more computing power,” said Erik Coelingh, Senior Technical Leader at Volvo Car Corp. “It might be attractive to have some distributed computing power, but much of the processing will have to happen in the central controller.”

When computing power is distributed, the various sensor systems will do some processing before they send data to the main ECU. As vehicles migrate from semi-autonomous to fully autonomous control, the aggregate computing power will have to rise dramatically.

“Centralized intelligence does not necessarily require a separate ECU; intelligence can be in the radar or camera,” said Kay Stepper, Regional Business Manager for Automated Driving at Robert Bosch Chassis Systems Control Division. “As we move to higher levels of autonomy, you’re talking about bringing in more intelligence.”

Software structures

Software architectures are an equally critical aspect of the control technique. Design teams have to determine how to structure software. Given the real-time demands of safety programs, software must be streamlined and written so that data can be understood quickly and easily. Most of today’s safety systems don’t have an operating system (OS), but it’s likely that the main ECU in a semi-autonomous car will need an OS to manage data.

“When all these disparate systems start merging data into one box, that’s where the OS comes in,” said Andy Gryc, Senior Automotive Product Marketing Manager for QNX Software Systems. “When sensor fusion occurs, it’s definitely a place for a safety-oriented operating system that’s been proven in military equipment, trains, and medical applications.”

Operating systems will let OEMs run various programs on a single CPU. Some companies are devising strategies that let automakers scale functionality, adding more options for more expensive vehicles. One solution is to mimic current consumer trends.

“The safety-domain ECU may be analogous with smart phones, acting as a host that can run a number of apps depending on the capability of the vehicle and the functions that the OEM wants to offer,” Whydell said.

E pluribus unum

Given the many sensors needed for semi-autonomous driving, most systems will comprise equipment from several suppliers. That means developers must find ways to ensure compatibility. Architectures will have to accommodate many different data types and multiple processors.

“Open programming models will be important; people need to do development based on an open standard,” said Davide Santo, Safety and Chassis Segment Manager at Freescale Semiconductors. “We don’t think a closed model is the correct way to go. The Open Computing Language (OpenCL) was developed by a consortium. It works with a massively parallel system and lets you standardize the way you talk to different elements. It lets you maintain coherency in your design.”

Programs will have to handle many types of data. That’s not just because input will come from radar and cameras. Vision systems alone often employ different types of processors.

“As far as artificial vision is concerned, the standard architectures available today go from reduced instruction set cores to vector accelerators, but none of them are optimal for all types of calculations,” said Paolo Ruffino, ADAS Marketing Manager at STMicroelectronics. “You’ll need them both for artificial vision and autonomous driving.”

Looking forward, managers must determine how to keep this software up to date. One solution to this challenge, which also exists in infotainment and other systems, is to transmit updates wirelessly. While the approach used for cell phones eliminates the expense of dealer visits for upgrades, the risks of altering safety software makes many companies nervous.

Over-the-air updates is an area where there’s a great deal of uncertainty,” Whydell said. “Clearly, with the growth of telematics, there’s a path to be able to do over-the-air updates. For OEMs, how to allow information from outside the vehicle to have access to the central system, including the ability to overwrite software, is unsettling. Over-the-air is the least secure way to update software.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...