Making Sense of Autonomy

Industry offers a range of sensors that will free humans from many tasks while also improving reliability, though devising strategies that meet demanding requirements without breaking the bank is no easy challenge.

Fully autonomous vehicles are just a sliver of the industry, but semi-autonomous technologies are paving the way for mainstream adoption. Strategies for sensing the vehicle’s surroundings will play an important role in the advance of piloted and driverless vehicles.

A range of sensors are being used to feed the controllers that make driving decisions. These sensors must provide enough information to ensure that automated braking and steering decisions are always perfect.

Devising strategies that meet this demanding requirement without breaking the bank is no easy challenge. Many design teams are moving forward incrementally, coming up with semi-autonomous systems that lighten the workload for drivers.

“Collision awareness provides a level of automated functionality that helps avoid collisions, but at a lower cost than a fully automated system,” said Jeff Wuendry, Industry Applications Specialist at SICK. “Damaging a single tire on a mining vehicle can cost more than $30k and this doesn’t include the losses in vehicle productivity, repair time, and safety reviews. Collision-awareness systems prevent costly accidents without the premium for fully automated solutions.”

Sensitive and smart

Sensor counts are spiraling upward as autonomous controls strive to collect enough information to identify objects with 100% certainty. Processing all this information similarly requires more computing horsepower. System developers need to meet demands with architectures that are cost effective yet still make good decisions that maximize safety.

One aspect of this challenge is to determine whether to package small, inexpensive processors into sensors or embed more powerful CPUs in sensor packages. That impacts networking requirements as well as overall computing needs.

“The computation power of sensors or sensor systems will increase,” said Carola Pfeifle, spokeswoman for Daimler AG’s Mercedes-Benz Trucks. “The challenge with raw data is the total amount of information that has to be processed and transferred into ECUs. A good system architecture helps to provide the optimal detail level of information to the features.”

Sensor makers are responding with multiple packages, letting users match their processing and pricing goals. This diversity is being augmented by declining prices, making it easier for system designers to get to market quickly with products that meet specific user requirements.

“The computing capability of sensors is either reducing the price of sensor manufacturing and development or increasing the sensor’s functionality,” Wuendry said. “From a sensor manufacturer’s perspective, the market is asking for both and the sensor manufacturers are able to provide more sensor options because development cycles continue to shrink.”

Leveraging the strengths of different types of sensors is becoming more common. Using a camera’s ability to discern shapes and radar’s proficiency in any weather or lighting conditions helps avoid false positives. Synchronizing these inputs can reduce sensor counts, but it requires more intelligence.

“Fusing data from multiple sensors takes a lot of computing power and memory,” said Don Remboski, Vice President of R&D and Innovation at Dana Holding. “Microcontrollers are getting cheaper by the day, so today it’s plausible to do things that were impossible a few years ago.”

Software obviously plays a critical role in system capabilities. Programmers continue to devise more ways to reduce the operator’s workload. Some feel that artificial intelligence can help systems adapt as workers perform repetitive tasks.

“There’s some machine learning,” said Mark Versteyhe, Manager, Advanced Powertrain, at Dana Corporate Research. “When a human uses a joystick to execute a difficult task, the machine recognizes patterns and can repeat them, the system can even improve efficiency.”

Frugal is the watchword

When OEMs increase the level of autonomy, they usually increase the number of devices that tell digital controllers about the vehicle’s surroundings. That move isn’t made without a major effort to ensure that cost and reliability don’t rise.

Reliability is more of a concern than with other semiconductor devices since sensors must interact with the real world. Micro-electromechanical devices have small moving parts that can be damaged in harsh environments.

“We assume that the total amount of sensors for autonomous features will rise,” Pfeifle said. “We will introduce new sensors or sensor principles if the overall failure rate will decrease and not increase anymore.”

One way to control this growth is to make sensors perform multiple tasks. That’s already being done, but engineers want to use sensors to see even more deeply into vehicle operations, using safety sensors to monitor mechanical components.

“You want to get dual use from the sensors,” Remboski said. “Antilock brake sensors now feed information to braking and traction-control systems. You can also understand component performance by analyzing vibration. Similarly, you can analyze problems in drivelines by analyzing vibration when you use the sensors’ maximum capabilities.”

Design teams are also looking at sensors that augment or replace the cameras and radar now used on many off-highway vehicles. Radar can see through the dust and fog common in many environments, but it doesn’t have good resolution and can’t identify objects. Cameras meet those requirements, but have trouble in dirty and dusty environments.

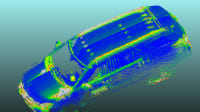

Lidar uses lasers to overcome many of the obstacles that hinder radar and cameras. It can provide range, depth, and resolution while peering through rain, snow, and fog. It’s been used in a range of high-end defense and mining vehicles and is being examined for more mainstream applications.

“An important application is looking for objects in non-ideal situations in industrial off-highway applications, for example, in the mining, agriculture, and construction industries,” Wuendry said. “While camera systems can be overwhelmed by particulates in the air like dust, lidar is not easily hampered by these conditions.”

However, cost is currently lidar’s Achilles heel. It’s been difficult to justify this expense except in very demanding applications. However, suppliers are racing to bring costs in line for off-highway equipment, partially because it will help them address the large passenger-car market.

Startups are also eyeing this arena. For example, three-year-old Quanergy is working with Joy Global Mining, which is using Quanergy’s mechanical technology as the startup moves toward a digital system.

“Our first-generation system, which is mechanical, broke the $1000 barrier when most Lidar systems went for between $30,000 and $80,000,” said Louay Eldada, Quanergy’s CEO. “Our solid-state systems will be at $250 when we start sampling at the start of 2016. The third-generation system will only cost $100.”

Diagnostic data

Adding sensors and processing power has benefits beyond driving vehicles along their chosen path. They can be combined to give operators and maintenance technicians more information. When drivers aren’t constantly controlling the vehicle, they’ll probably pay less attention to its performance.

“We focus on creating vehicles reliable enough to take on the mission when the driver isn’t totally in the loop minute to minute,” Remboski said. “Vehicles need to do more self-diagnosis and even self-healing. If there’s no driver, how do you detect a flat tire or a sticky brake?”

Sometimes, information about potential problems will be displayed on operator screens, other times it will be sent to remote maintenance staffs. It’s more challenging to send data remotely, since components, on-vehicle networks, and wireless links are all potential failure points.

“Our OEM customers are demanding higher levels of communication reliability and immediate notification if the communication may be compromised,” Wuendry said. “The difficulty in these situations is the inability of the sensor or the controller to know which device is at fault and then communicate that information through a different path.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...