Rethinking Architectures: From Chips to the Cloud

New concepts and strategies for controls architectures are emerging as AV boundaries expand and options skyrocket.

Creating a powerful, robust electronic controls architecture is among the most important tasks faced by those chosen to create autonomous-vehicle systems. Risk-averse developers who are devising scalable, efficient hardware and software strategies need to make tradeoffs between clean sheet designs and leveraging proven systems.

That’s only the start of the process. Adding parallel image processors to the conventional microcontroller base requires rethinking the mix of distributed and centralized computing power. Numerous suppliers will provide boxes and programs, driving a shift to open platforms. Even factors that were once trivial, like semiconductors’ power consumption, have become important.

“When you’re going to [SAE] Level 4 or higher, it can be safer, more secure and more robust if you start with a new architecture,” said Stephan Tarnutzer, Vice President, Electronics, Smart Vehicles, at FEV North America. “You can also account for higher power consumption. When you’re adding GPUs with 15-20W consumption alone, power is important. All the sensors also need power. It can be simpler to start from scratch.”

Although a new architecture always provides more freedom, engineers focused on reliability, safety and cost typically want to reuse proven technologies. In these early days of autonomy, some are using the PC’s virtual capabilities to learn how sensor systems work together to identify objects; PCs aren’t practical for production, but they help engineers create architectures that determine the right levels of distributed and centralized intelligence.

“Building an autonomous architecture would be much easier by leveraging any existing system/subsystems,” noted John Buszek, Director of Autonomous Driving Systems at Renesas Electronics. “Although, current PC servers utilized today in the autonomous space are stopgap solutions, consuming greater than 2 kW power and incurring a much higher cost than an embedded platform.

“To fully realize an autonomous driving capability, at minimum, the perception processing has to migrate to an embedded platform, fully decomposed for distributed processing,” he asserted.

Once companies establish the functional architecture for their vehicle, they move on to their technical architecture. OEMs are dealing with a number of system and software suppliers, typically building a number of partnerships to address the many facets of autonomy. That’s putting a greater emphasis on open platforms that allow carmakers to mix and match hardware and software, which will both be developed independently.

“That technical architectural approach looks at how things are connected and interface into the car,” explained Karl-Heinz Glander, Chief Engineer for ZF’s Automated Driving Team. “When hardware and software are abstracted from each other, software can be implemented by OEMs much more easily.”

When vehicles are making life or death decisions, there’s no room for failures. If electronics fail, they will typically downgrade to some sort of safe mode, often telling drivers that they must take control instead of relying on vehicle systems. Some designs include modules that watch over the sensors and CPUs.

“Many architectures are focusing on supervisory-type control, with controllers that serve no other task than to see if everything works,” Tarnutzer said. “If not, the main controller will drop down to Level 4 or Level 2 for safe operation. Supervisory controllers are not that powerful.”

Some OEMs are taking a different tack, providing redundant controllers capable of taking over if one of the domain controllers fails. This approach provides more safety but it’s more costly, because the redundant module must be as powerful as the controller it’s backing up.

Up in the sky

When system planners sketch their computing architectures, they’re no longer limited to the vehicle. Cloud computing can handle aspects that don’t require real-time responses, such as using high-definition mapping to help steer the car.

“Companies have to decide what processing they want to do on the vehicle and what processing they want to do in the cloud,” observed Scott Frank at Airbiquity.

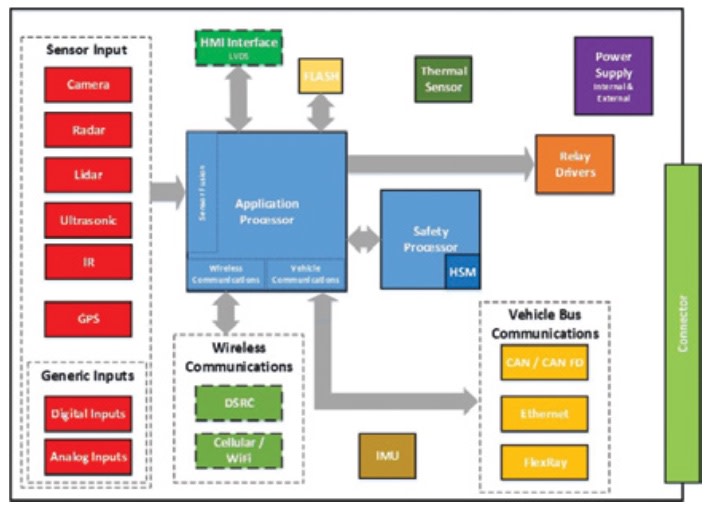

In the vehicle, that connectivity function will probably be integrated into gateways that collect data from safety systems and other controllers. These modules will typically have the capability to oversee many of the functions using input from a range of subsystems.

“We’ll probably see four or five domain controllers all coming together in a gateway,” Tarnutzer said. “Within the gateway, there will be a connectivity module for going to the cloud for things like data and over-the-air updates (OTAs).”

Designers typically obsess over factors like sensor resolution, processing requirements and power budgets, but they can’t ignore considerations like memory requirements. Flash memory sizes on microcontrollers have soared in recent years: Renesas’ RH850, for example, packs up to 16 Mbytes, but some designers think there’s need for more.

“Current CPUs have plenty of flash—from a pure execution standpoint, they have enough memory,” Tarnutzer said. “But I still see the need for external memory on the circuit board. It’s for data storage like high definition maps and some storage for OTA updates.”

Parallel Paths

After decades of dominance, conventional CPUs are going to be complemented by parallel processors. Graphic processing units (GPUs) popularized by Nvidia will be needed to handle image processing and artificial intelligence. Field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) provide an alternative path. Both alternatives have their tradeoffs.

“In general, GPUs and FPGAs will be chosen based on preference,” Tarnutzer said. “Some companies will jump on the Nvidia bandwagon, others will say GPUs suck too much power and cost too much, while FPGAs consume less power and can offer better cost. The question is whether FPGAs can be as efficient and powerful as GPUs.”

The selected technologies will be part of a computing hierarchy that includes a range of computing techniques. The computational workload for autonomy is daunting. At the same time, factors like power consumption are becoming more important as electronic content rises and electrified powertrains address range anxiety.

“For the most part, GPUs, CPUs and programmable devices like hardware accelerators or dedicated intellectual property within a ‘system on chip’ complement each other in various tasks,” Renesas’ Buszek said. “Each has its own advantages and disadvantages depending on the application/algorithm intended to be executed. For example, the major bottleneck, especially if artificial intelligence and deep learning is needed, is camera data processing. The programmable devices tend to show way better performance per watt than a GPU or CPU.”

Image processors will have to combine input from cameras, radar and lidar to create a single picture of vehicle surroundings. Sensor fusion is no simple task; data comes in at varying speeds and one sensor may see something that another misses. In just a few milli-seconds, the controllers must determine what’s actually there and decide whether it’s a threat. That takes a lot of computing cycles.

“All the sensors come from different backgrounds in history, so they all have different cycle times,” said Kay Stepper, Vice President for Driver Assistance and Automated Driving at Bosch North America. “You need to look at processing power and network speed when you’re doing fusion. The challenge is that the controller needs to make decisions based on a number of complete data sets that come in each second.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...