Fusing Sensors for the Automated-Driving Future

Complex processing architectures, faster networks and even more sophisticated software are vital for 100% accurate Level 4 and 5 systems.

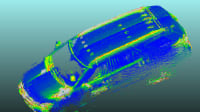

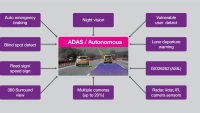

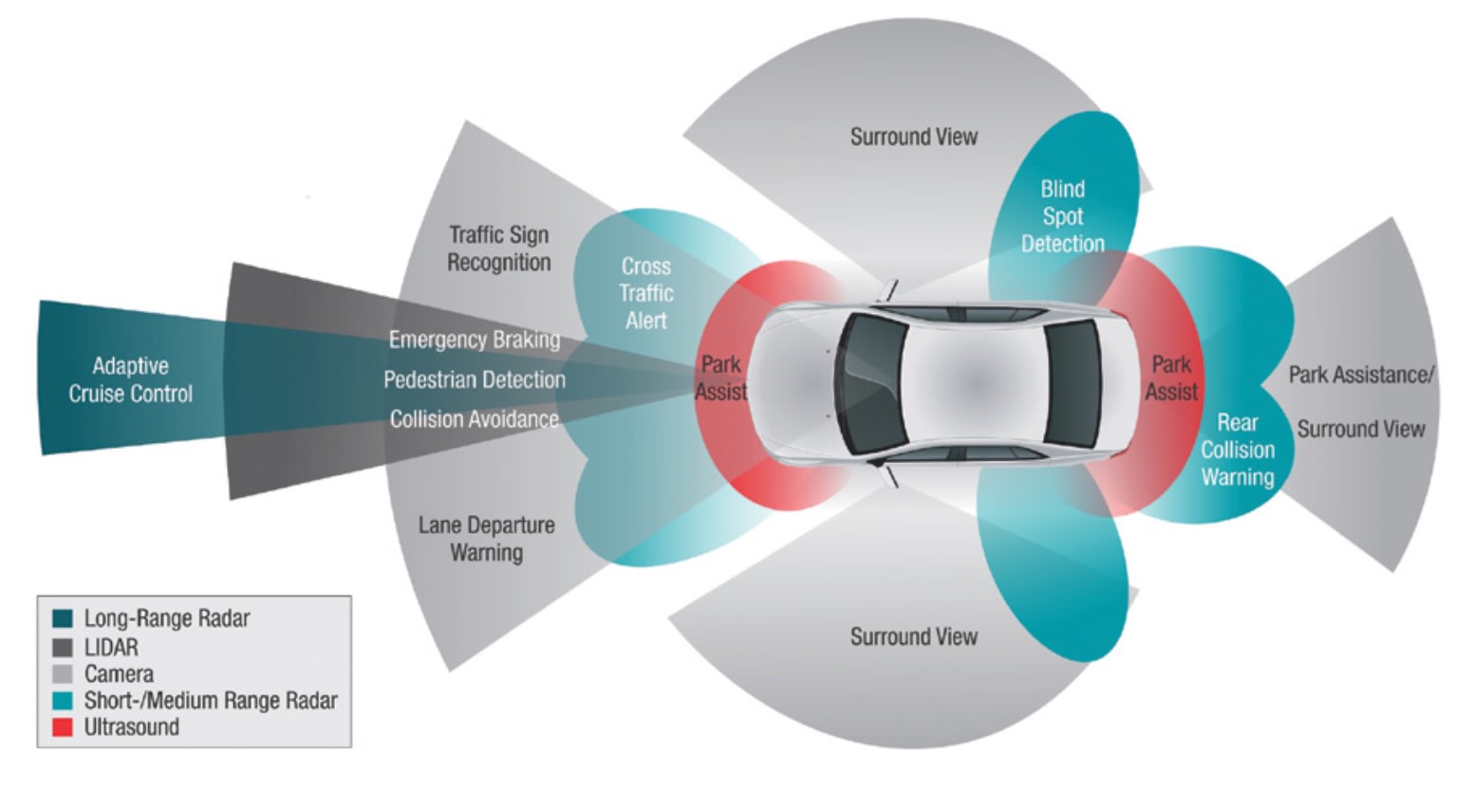

Piloted and autonomous driving systems depend on inputs from many types of sensors arrayed to create a highly accurate view of vehicle surroundings. Fusing all these inputs into a single image of each car, pedestrian and roadway marking takes a sophisticated architecture with hefty amounts of computing power and deterministic communications.

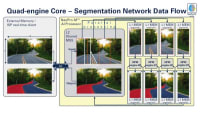

At highway speeds, combining inputs from multiple camera views is a complex challenge by itself. But different sensor types are needed to avoid errors, so vehicle controllers must blend inputs coming from multiple sensors and multiple modalities.

“Camera data comes in at 30 frames per second,” said Kay Stepper, Vice President for Driver Assistance and Automated Driving for Bosch North America. “Radar can have 20 to 50 or even 100 data sets per second, and lidar has a different time cycle all together. The first challenge is to bring all these data sets together to represent a single point in time, which requires some complex software.”

The challenge of merging multiple inputs will only get more difficult as the trek to autonomy continues. As vehicles advance to higher levels of the SAE automated driving scale, more sensor inputs will be needed. Some architectures may use more than two dozen sensors to create the 360° view needed for fully autonomous driving.

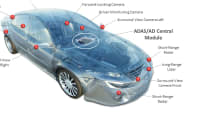

“Going from [SAE] Level 1 to Level 5, the sensor count goes from one or two up to 30 or more,” said Wally Rhines, CEO of Mentor Graphics, acquired by Siemens in early 2017. “To fuse all those inputs, you need software that lets you look at thousands of variations to get to an optimal design.”

Those programs will be complex, so techniques for continuing upgrades will need to ensure that much of the software can be reused. These programs will need to run on successive generations of hardware that will be deployed over many makes and models for years. Today, much software is written by the teams that create the hardware. Going forward, many planners want to move away from that model so it’s easier to upgrade and make changes like switching suppliers.

“Software reuse and hardware-software separation are becoming major issues,” said Paul Hansen, Editor of the respected Hansen Report on Automotive Electronics. “AUTOSAR and Automotive Grade Linux can help companies separate hardware and software so they can more easily switch vendors.”

More power

It will take a lot of computing power to collect all these inputs, analyze the data and make life-and-death decisions. The microcontrollers that have dominated electronic designs for decades will soon become one element in controllers that add graphics processors and custom devices that use parallel processing to handle images.

Many suppliers have partnered with Nvidia, which popularized the concept of graphics processors. However, Nvidia faces competition from FPGA suppliers like Xilinx and Intel, as well as mainstream automotive CPU suppliers like NXP and Renesas. They have licensed Tensilica’s programmable technology, planning to move it from infotainment applications to safety systems.

Once these devices are combined with conventional controllers, the ongoing advances in microprocessors should provide the processing power needed for successive generations.

“Graphic processing algorithms need very high-performance processors or specialized processors, which opens the market for companies known for gaming processors like Nvidia and Intel,” said Karl-Heinz Glander, Chief Engineer for ZF’s Automated Driving Team. “Devices that were used in infotainment are now going into safety applications. Given the advances tied to Moore’s Law, computing power will not be a limiting factor.”

These advanced architectures rely on real-time communications. The volume of data from sensors is a key factor that will drive a change in networking architectures, but it’s not the only aspect. Complex algorithms use concepts like occupancy grids, which consume bandwidth. Understanding where components are and routing the right data to them also increases bandwidth and timing requirements.

“The choice of bus communication depends strongly on the chosen vehicle architecture, number of sensors and fusion approaches taken. Additionally, the communication of occupancy grids and high definition maps between components, if necessary, enlarges the bus load requirements,” said Aaron Jefferson, Director, Global Electronics Product Planning at ZF. “We see a likely preference for CAN, CAN-FD and Ethernet.”

Going beyond CAN

Properly combining all the inputs to create a cohesive image requires exacting precision. Networks need to ensure that latency and other issues don’t cause timing glitches.

“CAN is no longer sufficient; you need a time triggered network,” Stepper said. “CAN-FD has time triggering, but there’s a clear migration to Automotive Ethernet because it has deterministic behavior and has the speed and bandwidth.”

Many companies plan to reduce some of these communications requirements by moving everything into a centralized controller. Most systems today use dedicated electronic control modules that don’t communicate at nearly the levels that will be needed by autonomous vehicles. That’s prompting many design teams to look at using one very powerful ECU.

“We prefer a centralized vehicle controller with a scalable architecture that goes up to SAE Level 4 and 5,” Stepper said. “Our centralized vehicle controller houses sensor data fusion and decision-making in one box.”

The ability to scale is always critical, but will be especially important as technology marches forward. Sensors improve, processors get more powerful, and engineers figure out ways to do more every year. Advances in one area typically beget progress in other fields.

“3D capabilities come from different ways to create and receive signals,” ZF’s Glander said. “As processing power increases, we can use higher and higher resolution imagers to extract more information and get wider sensing angles. Cameras are going from two to eight and even 10 mpixel resolution.”

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance