A Rebel’s Guide to Chassis Engineering

Herb Adams didn’t invent modern American car handling, though he was present at the creation. Back in the muscle car’s glory days in the mid-1960s to early ‘70s, Adams enjoyed several enviable engineering assignments at General Motors. One was assuring that Pontiac’s Firebird Trans Am was a markedly better performer than its platform mate, the Chevrolet Camaro Z/28. After that mission was accomplished for the 1969 model year, Adams applied lessons learned from a Trans Am road racing program to Pontiac’s Super Duty 455 production V8.

The result was one of the last and arguably the best-ever pony cars, the Firebird Trans Am SD-455, whose speed, power, and handling eclipsed anything offered by Porsche, Corvette and Jaguar during that period.

After a dozen years at GM, Adams had enough of big-company bureaucracy so in 1973 he left to design and engineer sports and racing cars as an independent. To share the knowledge he acquired, Adams published Chassis Engineering, a book that quickly became the high-performance handling expert’s essential primer and is still considered a “bible” by engineers in this discipline.

Having spent more than a half-century developing cars, Adams recalled the days before powerful computers and sophisticated software arrived to facilitate fast, accurate structural analysis. “Because we had neither CAD nor Finite Element Analysis, we had to improvise the design process with the tools at our disposal: pencil, paper, scissors, knives, cardboard, and model airplane cement. I call that science CEA — for Cardboard Element Analysis.

“We created 1/12-scale models of our structural concepts using cardboard or thin sheets of balsa wood in only a few hours,” he said. “By bending and twisting the resulting model in your hands, it’s easy to distinguish a good design from a bad one. While this technique yields no stress data, it does quickly reveal the most fruitful design directions long before the full-scale prototype stage.”

Increased stiffness, lower mass

While collaborating with a Shelby Cobra replicar manufacturer, Adams discovered why such cars have a well-deserved reputation for evil handling. The typical steel ladder frame is reasonably strong in bending but lacks torsional stiffness. Adding wider tires increases the forces fed into the frame, accentuating the need for adequate torsional stiffness.

“We knew that thin materials, such as sheet steel, have little resistance to bending but they’re extremely strong when loaded in shear,” he noted. “So, our goal was to replace the typical Cobra ladder frame with a tubular backbone design with most of the internal panels loaded in shear. Using CEA, we configured the cowl and rear cross members to transmit suspension loads to a large-section tubular backbone separating the driver from the passenger.”

In doing so Adams and his client achieved three gains: lower seating positions, higher torsional stiffness, and reduced weight. The final 300-lb (136 kg) frame provided an exemplary 13,000 ft·lb/degree torsional stiffness. “That’s a 10-fold increase over the original ladder frame’s stiffness combined with a 200-300-lb overall weight savings,” he explained. (In contrast to the original ladder design, Adams’s frame included the cowl and floor panels.)

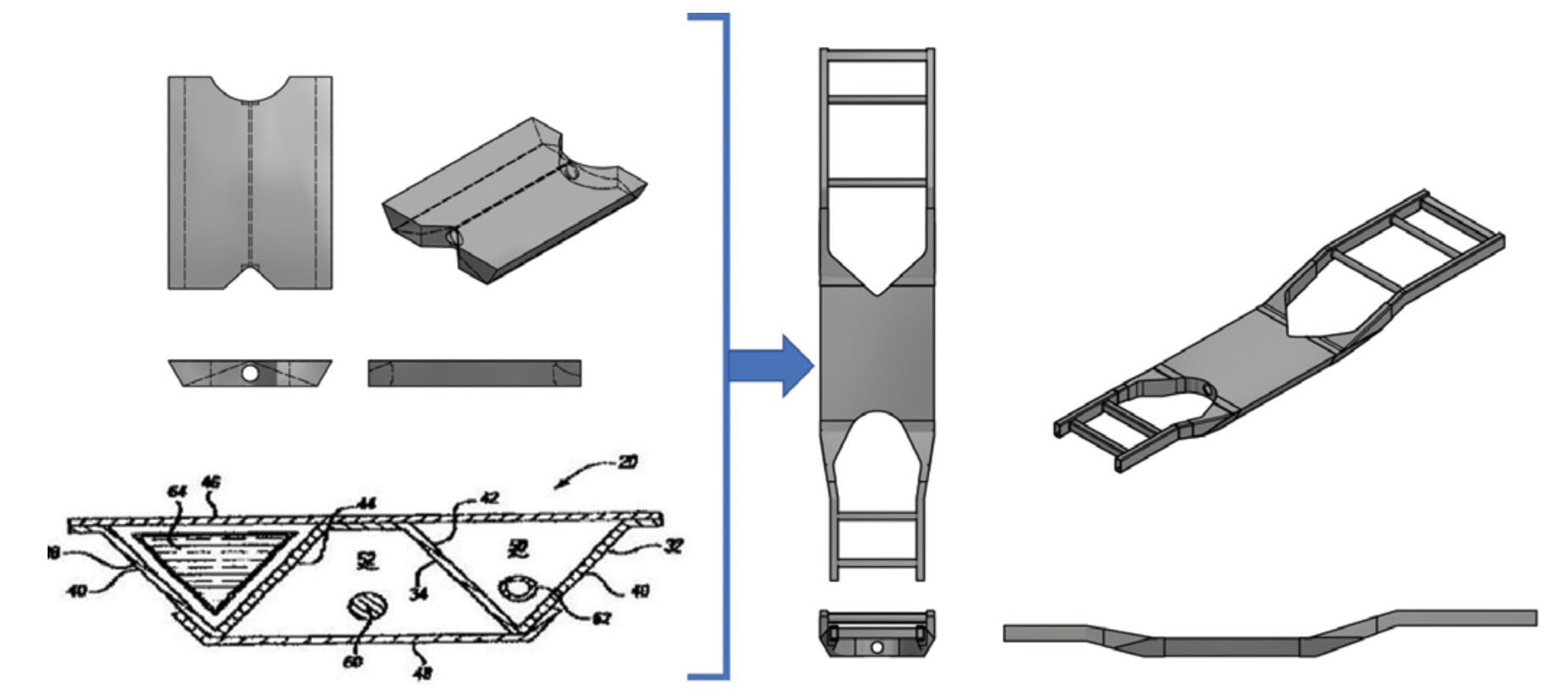

While the large tubular center section worked nicely in two-seat sports roadsters, that configuration doesn’t package well in other body-on-frame vehicles such as pickup trucks, motor homes, and trailers. Using CEA, Adams discovered that smaller tubes with a triangular cross-section also exploit the desirable shear-loaded-skin phenomenon. The eventual result was U.S. Patent 8534706 B2, issued in 2013, for what he calls the Adams Torsional Truss (ATT).

The inventor explains: “Three triangle-section longitudinal tubes are joined with two shared inner walls to form the center section of a frame that occupies about the same space as a conventional ladder frame,” he said. “Since the members are hollow, each could conceivably be used to contain fuel, exhaust pipes, and the vehicle’s prop shaft. The shear-loaded top panel could also serve as the cabin floor, saving additional weight.”

The panels of this sheet-metal-based torsion box can be roll-formed and joined using common welding methods or screwed in place when access to an inner cavity is required. “With an ATT serving as the center member, any desired front and rear section can be added as separate modules,” Adams said.

ATT for pickups, EV structures

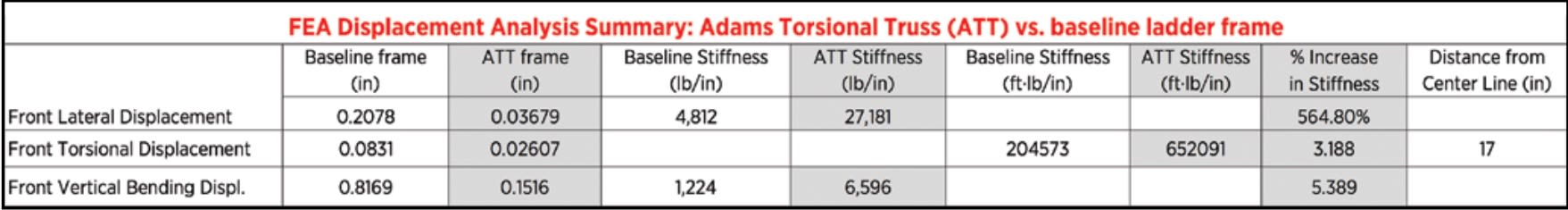

Instead of relying solely on CEA to prove his ATT theories, Adams hired David Valencia, a young Farmington, Michigan, engineering student, to conduct an FEA of his design. Using Autodesk Inventor’s Algor multi-physics software, Valencia compared ATT with a ladder frame consisting of two 3 x 6-in (76 x 152-mm) and 3 x 8-in (76 x 203-mm) longitudinal rails braced with nine cross members.

Three different load situations were studied: front lateral, front torsional displacement, and vertical bending.

The analysis revealed that ATT reduced maximum stress by 3% to 33% while increasing stiffness by 3.19% to 5.39%. The ATT design consisted of 0.060-in-thick (1.5-mm) A36 sheet steel throughout, yielding a 40-lb (18-kg) mass savings over the ladder frame; see chart.

Point proven, Adams could advance his cause by investigating alternative materials and metal gauges to optimize cost, mass, and performance. He believes that retaining a hybrid design — an ATT center section joined to conventional ladder front and rear sections — is the quickest way to bring this technology to market.

With improved fuel economy an ongoing design imperative and manufacturing costs a constant concern, Adams believes his ATT approach would prove valuable to suppliers and OEMs. He is encouraged by two recent developments — the move to aluminum for pickup cabs and beds, and battery-electric vehicles with a floor structure serving double duty as the battery enclosure.

And while Adams’s stone-simple and straightforward CEA has no potential as a revenue producer, this throwback technology could be a handy (literally) educational tool. Why not supplement the on-screen lessons learned by today’s engineering students with a hands-on feel for a design they’ve created using cardboard, scissors...and model-airplane cement?

Top Stories

INSIDERDefense

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

Road ReadyTransportation

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Power

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Connectivity

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Transportation

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Aerospace

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance