DSD Helps ‘Balance the Books’ for Buying Electric Truck Technology

In the discerning world of truck operations, where procurement decisions must be based on total cost of ownership (TCO), the case for moving to environmentally sustainable electric powertrains for heavy commercial vehicles that demand high initial capital outlay and bring concerns over range limitations, yet lower running costs, is a constant conundrum. But it may be solved via a new simulation system that matches powertrain characteristics to specific applications of an operator to achieve “significant” cost savings without compromising required range.

Developed by UK company Drive System Design (DSD), its chief engineer Mike Savage explained the whys and wherefores of the system: “We have pioneered a simulation process called ePOP (electrified Powertrain Optimization Process), in which the electrified powertrain is optimized for cost and range as a complete system, rather than focusing on individual elements.”

Traditional tools and processes used to design and optimize powertrains are time-consuming and fragmented, he claimed, with results that are often constrained by subjective views or an unconscious bias towards “known solutions.” He said that whatever the improvements in individual technologies, such as the motors or battery packs, the maximum benefit would only come from using a fully considered system-level approach that would lead to more competitive truck operations.

Isolating the optimal configuration

DSD’s ePOP permits what Savage described as “exhaustive” investigation of alternative electric powertrain options for any particular application. To demonstrate this, the company completed a study for a 13-tonne single rear axle truck, during which more than 4,000 powertrain permutations were evaluated to isolate the optimal configuration.

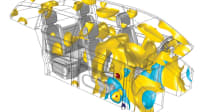

Savage explained that the key enabler in the process is the characterization of subsystem and component designs by their major properties, allowing the building of complete powertrain variants for simulation: “ePOP rapidly generates the necessary input data (masses, efficiency maps, etc.) for each electric powertrain subsystem for a range of topologies and layouts. It is this speed of data generation that permits the simulation of such a large number of powertrain configurations, which are then compared through intelligent cost functions and trade-off algorithms.”

Interestingly, what Savage described the “rigor” of the ePOP approach meant that unexpected and counter-intuitive solutions are often exposed, which might otherwise have been discounted or just overlooked. In that case, changing to a more expensive, more efficient e-motor permitted a significant reduction in battery pack size while maintaining the desired range, because across the drive cycle the more efficient e-motor drew less energy from the battery pack, which could therefore be reduced in capacity. He cited a similar effect sometimes being observed when introducing multi-speed transmissions in order to downsize the e-motor: “In each case, the overall result is a lower cost for the total powertrain and a reduction in weight.”

Detailing DSD’s new system, Savage stated that the process compares different specifications for the powertrain which are derived by computing the vehicle resistive power during a range of operational use cases, calculated using models based in MATLAB/Simulink from MathWorks. The vehicle model uses road-load equations to account for the vehicle inertia, rolling resistance, aerodynamic drag and gradient to calculate the power and torque required at the wheels, verified against measured data.

“Based on the vehicle’s functionality, hypothetical targets provide a basis from which the power and torque required are calculated, for example using top speed targets, minimum gradeability and minimum range required,” said Savage. “Actual range is then determined by calculating the energy consumption during the drive cycle, in which the vehicle is subjected to a range of accelerations and decelerations, based on the battery capacity and opportunities for energy recuperation through regeneration.”

The vehicle specification and targets are not only inputs to the vehicle model, but also used to intelligently define and limit the range of powertrain subsystems to be analyzed, he stressed. The selected powertrain combinations are simulated to analyze the performance of the electric vehicle and the range over drive cycles of interest. ePOP models subsystems and components to create input data for a range of inverter, e-motor, and transmission variants, tailored to the requirements of the application. The process generates each subsystem’s characteristics, required for the vehicle simulation and cost functions.

Cost vs. range

“As ePOP has generated each subsystem specification itself, sufficient data is known about the subsystem and its constituent components to determine relative cost estimates. The information provided (early in the design process) by adopting an analytical system approach gives the user the ability to understand and leverage the complex trade-offs that exist between the main powertrain components,” stated Savage, adding that an accurate assessment of cost versus range allows the user to explore the design alternatives and determine the best powertrain for the given application.

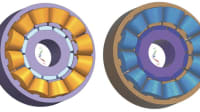

Experience with the ePOP approach has shown that drive cycle energy consumption must be optimized, rather than outright peak efficiency, Savage stressed. In the case of different e-motor magnet topologies, with different efficiency map characteristics, the transmission influences the optimum selection. Two-speed transmission variants can be utilized to take advantage of peak efficiency but require further optimization to outweigh associated costs, such as the extra ratios and shift system.

“Though the process has a broad range of applications, the trade-offs are specific to a particular vehicle type and its usage,” said Savage. “This avoids ‘one size fits all’ design solutions and leads to a powertrain that is genuinely optimized for its intended purpose. The key to successful application is a thorough understanding of the operational use cases in order to specify power and torque appropriately. An optimized powertrain can then be identified that maximizes energy efficiency at minimal cost.”

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance