Aerospace Aluminum Laser Welding: Advancing Material Performance for the Future of Flight

Between the 1920s and 1930s, aluminum started replacing wood as the primary material in aircraft construction and soon became the backbone of modern aviation. Its popularity stemmed from a combination of properties, high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and ease of forming that made it ideal for demanding aerospace applications. Throughout much of the 20th century, high-strength aluminum alloys dominated aircraft design, accounting for 70–80 percent of commercial airframes and more than half of many military aircraft. Even after the introduction of fiber–polymer composites in the early 2000s, aluminum has remained a critical material because it continues to offer the strength, lightness, and versatility needed for modern aviation.

Industry forecasts predict that commercial air travel will double in the next 25 years, which means more pollution will be released into the atmosphere. One way to help reduce these emissions is by building airplane fuselages and wings with lighter and stronger materials.

The development of aerospace aluminum alloys can be traced through several generations. First-generation alloys were mainly 2xxx (Al–Cu) systems, offering high strength but poor corrosion resistance. Second-generation alloys, built around 7xxx (Al–Zn–Mg–Cu) systems, delivered much greater strength for wings and fuselages but were vulnerable to stress corrosion cracking. Third-generation alloys refined these 7xxx systems with microalloying additions such as Zr and Cr, significantly improving toughness and corrosion resistance while providing a better balance of performance and safety. Fourth-generation alloys advanced further by combining high strength with superior damage tolerance and fatigue resistance. This group includes both improved 7xxx alloys and aluminum–lithium (Al–Li) alloys, where lithium additions reduce density and increase stiffness, making them highly attractive for modern aircraft and space applications.

Aerospace Aluminum Joining: Methods, Challenges, and Structural Integration

As aluminum is unique in aerospace manufacturing, it has required specialized joining methods across all generations of alloys. Techniques such as friction stir welding, adhesive bonding, and riveting have been widely applied to produce lightweight yet durable aircraft and spacecraft structures, but each introduces its own challenges:

First-generation 2xxx (Al-Cu) alloys are highly prone to hot cracking and the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds like Al2Cu, which weaken welds.

Second- and third-generation 7xxx (Al-Zn-Mg-Cu) alloys suffer from severe liquation cracking in the heat-affected zone, porosity from zinc evaporation, and loss of strength due to averaging during welding.

Modern Al-Li alloys (e.g., 2050, 2198, 2099), while designed for better toughness and weight reduction, still present difficulties such as lithium evaporation, porosity, and altered precipitation behavior that can degrade weld quality.

In addition to these metallurgical challenges, the joining processes themselves introduce further complexities. Each method presents its own set of limitations:

Friction stir welding requires precise heat control due to aluminum’s high thermal conductivity and low melting temperature; without it, voids, tool wear, or distortion may occur.

Adhesive bonding must overcome aluminum’s surface oxide layer, maintain strict cleanliness, and ensure longterm durability under variable thermal and mechanical loads.

Riveting, though long established, adds weight, introduces stress concentrations that can trigger fatigue cracking, and requires sealing to prevent galvanic corrosion.

Wire-feed laser welding can introduce filler material to bridge gaps and reduce cracking, but it adds complexity in process control and risks of porosity or lack of fusion if feed and energy are not precisely coordinated.

These limitations and complexity make aluminum joining across all generations of alloys highly specialized, demanding rigorous process control and inspection to guarantee structural safety and performance in flight. To meet the need for lightweight yet strong designs, many major load-bearing components such as beams, bulkheads, and wall panels are increasingly manufactured as integral structures machined from large solid blanks, incorporating grooves, ribs, bosses, and lightening holes.

Advantages and Challenges of Autogenous Laser Welding in Aerospace Aluminum Alloys

Autogenous laser welding, in which joints are formed without the addition of filler wire, has attracted significant attention for aerospace aluminum structures because of its potential to deliver lightweight, high-precision welds with minimal distortion. The concentrated energy of the laser beam enables deep penetration at high travel speeds, reducing heat input compared to conventional arc welding and limiting residual stresses. These features are especially valuable for thin-walled aerospace components, where weight savings and dimensional accuracy are critical.

However, the autogenous approach also exposes the inherent weldability problems of aluminum alloys. Hot cracking is a major concern, particularly in 2xxx (Al-Cu) and 7xxx (Al-Zn-Mg-Cu) alloys. Without filler material to modify the solidification path, the weld pool is highly susceptible to segregation and crack formation. Porosity is common due to hydrogen solubility and the evaporation of volatile elements such as Zn, Mg, or Li. Metallurgical limitations vary across alloy systems. In 2xxx alloys, brittle Al 2Cu phases often form and weaken the weld. In 7xxx alloys, welding can lead to overegging, a loss of precipitation hardening, and severe liquation cracking in the heat-affected zone. For Al-Li alloys, lithium evaporation, porosity, and degradation of weld metal properties are the main concerns.

New Novel Approach for Laser Welding Aerospace Grade Aluminum

Using fiber lasers to weld aerospace aluminum alloys across all generations, 2xxx, 7xxx, and modern Al-Li has historically been difficult due to hot cracking, porosity, distortion, and loss of mechanical properties. Most available industrial fiber lasers can be modulated from Continuous Wave (CW) to pulses in the millisecond range, which helps reduce heat, focus energy in small areas, and make welds more stable. Modulating the laser at the microsecond level provides an additional layer of precision, offering more ways to control heat, minimize the heat-affected zone, and improve absorption, especially since aluminum reflects laser energy about four times more than steel. Additional progress has come from fiber lasers with core-and-ring beam designs, which provide flexible energy distribution by directing more intensity through the core while using the surrounding ring for stabilization.

Delivering energy in short microsecond bursts reduces overall heat input, concentrates energy in a small localized area, and stabilizes the weld pool. With precise control over how energy is delivered, microsecond pulses minimize excessive thermal penetration, shrink the heat-affected zone, and mitigate challenges related to aluminum’s high reflectivity nearly four times higher than steel when using fiber lasers. Even greater improvements come from laser modulation, where the power and timing of the core and ring can be independently adjusted, enabling more strategic energy distribution between penetration and pool stabilization.

Because each generation of aerospace aluminum alloys contains different elemental compositions, they respond differently to heat and solidification. For this reason, tailored pulse shapes are necessary to manage heat flow, limit defects, and ensure stable welds. Properly designed pulses not only reduce the heat-affected zone but also balance penetration, cooling, and material stability. Independent control of the core and ring pulse shapes further improves absorption efficiency, reduces defect formation, and provides the flexibility needed to adapt welding parameters to the unique behavior of each alloy generation.

Beam oscillation adds another layer of control by spreading laser energy over a defined path, lowering stress concentrations, improving keyhole stability, and enhancing weld uniformity. Each generation of aluminum alloys benefits from a specific oscillation profile, with tailored scan width and scan frequency to match its metallurgical characteristics. Oscillation can create edge effects, where energy density is higher at certain points, but these must be carefully managed to avoid hot spots that cause defects such as porosity, cracking, or distortion. When applied correctly, oscillation places heat exactly where it is needed for reinforcement while preventing overheating, leading to better sidewall fusion, reduced porosity, and consistent weld quality.

Molten aluminum can absorb large amounts of hydrogen, which forms gas pores as the metal solidifies, one of the main causes of porosity in laser welds. In aerospace applications, hydrogen often comes from air surrounding the welding process. Using high-purity argon (Ar) shielding gas helps prevent hydrogen pickup. Careful adjustment of gas flow, nozzle design, and coverage ensures full protection of the molten pool and minimizes porosity.

Summary and Engineering Implications for Aerospace Aluminum Welding

Together, microsecond pulsing, alloy-specific pulse shaping, core-and-ring beam modulation, and controlled oscillation provide far greater precision than CW welding. These methods make it possible to successfully join even the most weld-sensitive aerospace aluminum alloys, delivering stronger, lighter, and more reliable results for critical applications.

This article was written by Dr. Najah George, Senior Director of Research and Development Photon Automation, Inc. (Greenland, IN). For more information, visit here .

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

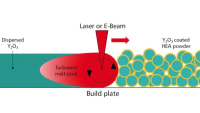

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsUnmanned Systems

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

ArticlesTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

Road ReadyTransportation

![]() 2026 Nissan Sentra Review: Putting the Pieces Together

2026 Nissan Sentra Review: Putting the Pieces Together

NewsTransportation

Webcasts

Automotive

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Automotive

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Internet of Things

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Defense

![]() SiPhog Technology: Enabling GPS‑Independent Flight for Uncrewed Aerial...

SiPhog Technology: Enabling GPS‑Independent Flight for Uncrewed Aerial...