Lightweighting to Improve Off-Highway Emissions

Where systems engineers can gain efficiencies in off-highway equipment is agnostic, they’ll take it anywhere, and so they should, but one of the ways, often underestimated, is through the use of strong and lightweight advanced materials.

In many segments of the ground-vehicle industry, lightweighting is a hot topic, and yet the off-highway segment lags behind in terms of more eco-friendly vehicle design. However, legislative pressures are inspiring change.

Automobiles are thought to be responsible for around 12% of total EU emissions of CO2, the main greenhouse gas. In response, EU legislation has set mandatory emissions reduction targets for new cars — by 2021, the fleet average of CO2 to be achieved by all new cars is just 95 g/km, a reduction of 40% when compared with the 2007 fleet average; an engineering challenge not new to the off-highway industry.

Lightweighting is one answer to the emissions problem and the automotive industry has been quick — and able — to respond, with multiple new products and solutions. Ford has recently announced its collaboration with DowAksa and the U.S. Department of Energy to “develop manufacturing innovations in automotive-grade carbon fiber for use in future products,” and the Mercedes GLC is constructed from “a high percentage of lightweight parts, with high-strength steel and aluminum used extensively in the chassis and suspension.”

Modern steels, despite receiving less press than other solutions, remain a popular option for weight reduction. General Motors’ Chevy Malibu, for instance, demonstrates 300 lb (136 kg) of weight savings, more than a third of which comes from the redesigned body structure, which utilizes thinner, high-strength steel components in some areas.

Lightweighting engineering challenges

While lightweighting has long been a popular option for reducing emissions in the automotive sector, it continues to be less so in the design of off-highway vehicles, and there are many reasons for this. One is that the duty cycles of off-highway vehicles tend to be unpredictable because the applications the owner uses them for are so wide ranging.

One example is telescopic handlers, which are designed for pick and place operations but can be used for many diverse applications from shoveling material to driving in posts. Even if OEMs were able to design for every possible application, the resulting product would be unfeasibly expensive to produce. However, there is a balance to strike.

Farmers need products that meet all of their needs — a Swiss Army knife approach. The key is developing a vehicle that is as capable as efficient design and engineering allows and demonstrating to buyers this range of abilities. In comparison, automotive designers can work to very specific requirements. Drivers understand the limitations of their vehicles and work within them.

Another reason is the unpredictable nature of the loads themselves, due to the range of operations a single machine may be used for in its lifetime. Without predictable loads it is difficult to use simulation to accurately predict stress levels and hence to ensure that the equipment would be able to stand up to all conceivable tasks. The same is true for the unpredictability of the conditions these vehicles work in.

Due to the large variety of applications of off-highway vehicles, in the past there was very little legislative requirement for the performance of this equipment, with the exception of safety regulations in roll-over and falling-object protection systems (ROPS and FOPS). In comparison, automotive design is extensively legislated — for example, crash performance — which leads to an understanding and expectation of the loads on a vehicle structure. This is a benefit as all vehicles have to meet the same standards.

In addition, a lot of attention has been diverted away from reducing weight in off-highway vehicles due to the large amount of investment needed over the last few years in getting engines up to Tier 4 standards. These regulations, phased in over the period of 2008-15, required that PM and NOx emissions be further reduced in new off-highway diesel engines by around 90%. For many companies it is only now that they are able to free up the level of investment needed for researching and developing lightweighting. Since next-stage environmental legislation will be harder to reach, engine manufacturers, OEMs, and other system suppliers must find other ways to differentiate themselves and gain competitive advantages over rivals.

But while the off-highway sector has tended to lag behind, there are a number of ways in which it could learn from the more technologically advanced automotive industry. A tool that has been used in automotive for 20 years and which could offer learning to the off-highway sector is multi-body dynamics, an analysis tool that allows engineers to study the dynamics of moving parts and predict the forces in mechanical systems.

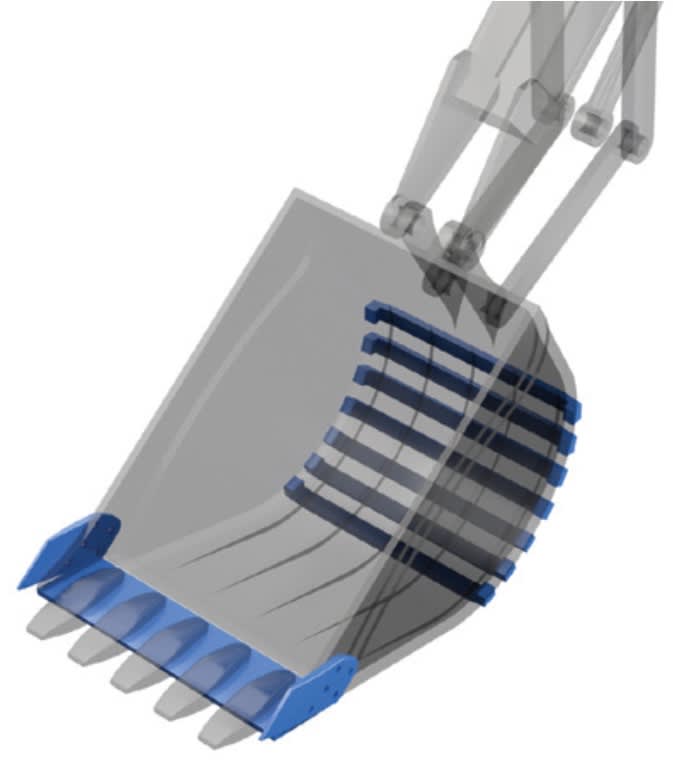

This tool is starting to be used in off-highway, but progress is slow because there isn’t yet a reliable model for one of the key parts of off-highway durability cycles — the soil-bucket interaction model. The modeling of soil is in itself a complicated process. The loading put on the vehicle by cutting through the ground is hard to calculate, and since excavators will be expected to dig a whole range of different materials — from sand to clay to rock — there is also a large disparity between the loads exerted by these materials.

A key focus for the off-highway industry as it strives to meet potentially stricter “Tier 5” emissions targets will be formulating the soil models needed to exploit multi-body dynamics to optimize the vehicle and catch up with advanced automotive models, which take into account both loads and the ride and handling of the vehicle.

The right materials

NVH (noise, vibration, and harshness) optimization is another example of an area of study that is carrying over from one discipline to the other. A key focus for the industry is designing vehicles that feel more like a car to drive, both reducing strain on the operator and offering comparable performance on all terrains, whether that’s on road between fields or off-road across them.

A recent example of this work is the new JCB Fastrac 4000 where one of the design challenges was to design a vehicle that is more comfortable for the driver. With this in mind, the chassis had to be optimized to reduce vibration, and the operator cab was completely reworked to allow for a significant increase in glazed area to give better visibility. For this purpose, optimizing the stiffness of the chassis structure was an important focus area.

The challenge with improving driver comfort and vehicle durability is to increase the chassis stiffness without adding weight to the vehicle, which would compromise meeting emissions targets. To meet these multiple and often conflicting objectives, clever design is required to improve the vehicle without adding weight. Reducing parasitic mass is a common area of study for off-highway designers.

While weight is needed in certain parts of the vehicle, either for stability or to react to digging loads, there are also areas where gains can be made. An example of this is the arm of an excavator, which can be considered as parasitic mass as its prime function is to support the loads from the bucket.

Another area is in the design of ROPS. While strength in these parts is essential for safety, most of the time it is dead weight. OEMs in the off-highway industry are working to better understand the impact of parasitic weight and how reducing 10 kg (22 lb) from the boom, for instance, would improve fuel efficiency.

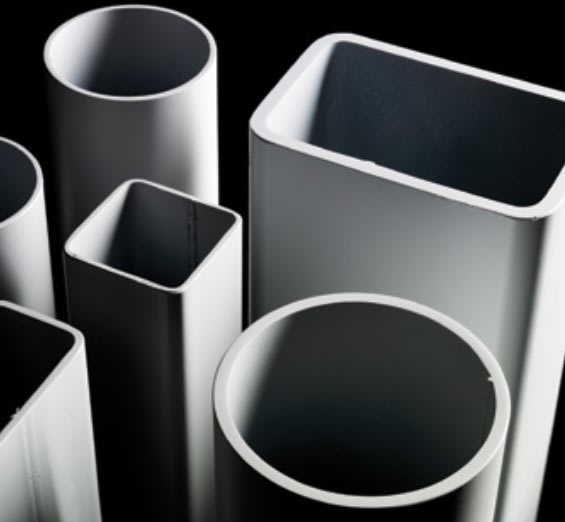

One key factor steel suppliers have been quick to recognize is that using the right material in the right place is an important way of optimizing vehicle design. While lighter, more modern materials such as carbon fiber and aluminum have their part to play, particularly when trying to reduce weight, for the foreseeable future steel will still account for 80% of the structure of off-highway machinery such as backhoe loaders.

In some cases, the steel will need to be highly abrasion-resistant steel for applications such as construction, aggregates, and quarrying. For example, steels with 400 and 450 Brinell hardness that can work at temperatures down to -40°C (-40°F) would be suitable for tough mining and quarrying conditions. Such steels could be used in thinner sections to replace conventional steels, in dump trucks and dustcarts for instance, providing an effective way of reducing weight. Also, in many applications a steel can be chosen with a low carbon-equivalent value, making it easily weldable and allowing high-strength components to be produced without changing standard weld procedures.

Manufacturing knowledge

Reducing weight in the structure is just a starting point, however, and opens up a whole host of opportunities for improving processes throughout the manufacturing cycle. As weight is reduced in the structures of off-highway vehicles, designers can in turn look to a more automotive manufacturing process, utilizing pressing and folding to reduce the amount of welding. The automotive industry uses spot welding that is high quality and well understood. In general it is the case that spot welding is independent of material grade and allows for the upgrading of steel to advanced-high-strength steel (AHSS) without any joining issues.

In comparison, the off-highway industry uses MIG welding designed to the BS7608:2014 standard — a more conservative approach. The benefits of using higher-strength steel are not reflected in an extension to the weld fatigue life.

What is needed is for off-highway manufacturers to establish a less conservative welding design environment based on understanding stresses more accurately through detailed analysis and an extensive test program of “real loading cases and joint configurations.” This deeper understanding of the weld stresses is required to fully exploit the advantages of AHSS and move toward lighter-weight structures utilizing the benefits of AHSS and lean engineering.

The steel industry itself is committed to reducing emissions and one initiative, HIsarna, has received a significant boost recently, in the form of a €7.4m funding boost from the EU. The HIsarna project is testing a new iron-production process that is being developed at Tata Steel’s IJmuiden steelworks in the Netherlands. If the technology is viable and can be scaled up, steel companies would be able to use a wider range of raw materials, including recycling materials, and the technology would lead to 20% lower CO2 emissions.

Learnings from one industry often influence development in another, and in that sense the automotive, aerospace, and off-highway industries have all benefited or been inspired in some way, big or small, from the other. With the pressure now on for off-highway OEMs to meet strict Tier 5 emissions standards, the focus on lightweighting these traditionally heavy weight vehicles will come to the fore.

This article was written for Off-Highway Engineering by Derick Smart, Customer Engineering Manager, Tata Steel.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...