Assembling Aluminum Vehicles in Volume

Ford’s 2015 F-150 pickup pioneers high-volume mass-production of lightweight aluminum car and truck structures.

The next six months will be challenging times for Ford workers. Dearborn has redesigned its best-selling and most profitable model, the F-150 pickup truck. The tried-and-true, all-steel truck has been jettisoned for an all-new mixed-metal design that pairs an aluminum body and cargo box atop a ladder box frame that is three-quarters high-strength steel.

The new configuration means that the company’s pickup truck assembly lines will have to retain resistance spot-welding systems to make the rolling base and also install a far more complex aluminum-joining process that relies on mechanical fasteners and industrial adhesives for the upper structures.

Ford’s pioneering move to mass-produced aluminum structures — annual volume of about 650,000 units is 10 times the number of niche-market luxury vehicles made of aluminum — will require Ford assembly lines to maintain bulletproof production quality while spitting out 60 jobs per hour, a feat not yet demonstrated with aluminum bodies and boxes.

“We used our analytical tools to preview various materials for lightweighting vehicle structures,” said Peter Friedman, Manager of the manufacturing research department at the Ford Research and Innovation Center. That research helped the automaker cut hundreds of pounds of weight and enables further synergistic downsizing effects on secondary systems to improve both fuel economy and performance.

“At the same time,” he said, “we had to ensure the truck would be as tough as, or tougher than, the current model.”

Of all the materials tested and analyzed, “only certain ‘military-aerospace’ grades — 5000 series (aluminum-magnesium) and 6000 series (aluminum-magnesium-silicon) alloys — met our goals and could be produced in volume at high quality,” said Friedman.

Next, Ford worked with its aluminum suppliers — Alcoa and Novelis — to fine-tune the compositional specifications of the alloys and establish a closed-loop recycling system that could minimize costs by exploiting the large quantities of aluminum scrap.

Ford is not alone in its intentions to build more aluminum vehicles. General Motors and Fiat-Chrysler are thinking the same way. By 2025, more than three-quarters of all new pickup trucks manufactured in North America will have aluminum bodies and closure parts, said an automaker survey conducted by Drucker Worldwide for the Aluminum Association. The study predicted that the domestic car makers’ production of aluminum pickup trucks, sport-utility vehicles, and both midsize and full-size sedans will make them the biggest users of aluminum sheet in the coming decade. Aluminum body structures will account for 18% of domestic production.

Aluminum joining and fastening techniques have long been used in aerospace and military industries, but they were adopted by the automotive business only relatively recently and for low- to moderate-volume builds of cars such as the Audi A8, Jaguar XJR, and Range Rovers. Ford decided to mass-produce aluminum vehicles to meet looming fuel-economy regulations.

Plus, Friedman declared, “We have a lot of experience with aluminum joining methods.”

Assembling aluminum

In 1993 the experimental Mercury Sable AIV (aluminum intensive vehicle) program — “essentially 40 aluminum Tauruses” — used weld-bonding, which is a combination of resistance spot welding and adhesives, Friedman said. “And the first aluminum Jaguar XJ, back when Ford owned Jaguar in 2003, was rivet-bonded — rivets plus adhesives.”

Next year’s F-150 pickup “has a little bit of both approaches,” Friedman continued. “We use fasteners, both self-piercing rivets and flow drill screws, and spot welding where it makes sense. In addition, we’re using more than three times as much adhesive bonding as the previous truck — hundreds of meters of it.” Think of using both fasteners and glue like wearing a pair of pants with a zipper and buttons. Either one works alone, but both is better.

The design and manufacturing engineers’ choice of method for each joint, he explained, was determined both by in-service requirements — performance, appearance, and so forth — and manufacturability. “Let’s say that we’re trying to join a sheet part to an extruded part and we have access to only one side because it’s a close-out panel. Because of the limited access, we might use flow drill screws,” Friedman explained.

These constrained access conditions occur in 15% of the F-150 structure.

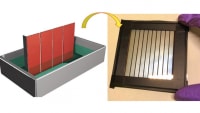

Aluminum spot welding

“Steel car structures have traditionally been resistance-spot-welded,” said Zhili Feng, Leader of the materials joining group at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ONRL). Spot welding uses two opposing electrode pincers to compress and fuse pieces of metal together, using an electrical current to create intense heat to form a weld. “You can do the same with aluminum, but you need a much more powerful electrical supply because aluminum is highly conductive and doesn’t heat up as readily as steel does, so you need more current.”

In addition, exposed aluminum creates aluminum oxide scale in air, “so you’ve got to clean the surface as they do in aerospace manufacturing,” Feng continued. “Otherwise, oxygen and hydrogen come out and get into the weld where they can cause quality issues.” Cleanliness is much more important with aluminum spot welding.

“In the last two years or so, GM patented an improved resistance spot welding process that breaks down the surface coating,” Feng said. The process replaces standard smooth electrodes with a multi-ring domed electrode. The modified welding technique works on sheet, extruded, and cast aluminum because the proprietary electrode head disrupts the weld-weakening surface oxides. GM is joining aluminum body parts such as hoods, liftgates, and doors, often eliminating several pounds of rivets.

Self-piercing fasteners

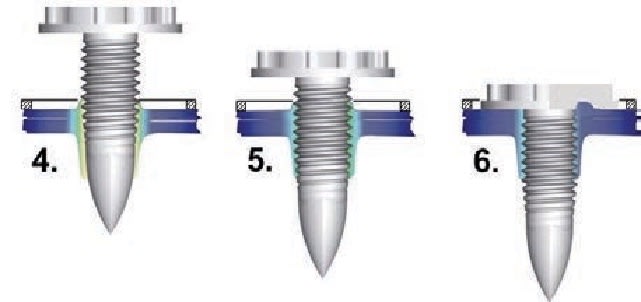

“For some products, car companies use self-piercing rivets — fasteners with sharp tips that are applied at high pressure. Then the end is folded over with a tool to form a mechanical interlock,” Feng said. Not only must thousands of rivets of various types be delivered to the proper place along the line at the right time, they must be inserted smoothly, then formed over into a perfect mushroom shape, and then inspected.

The self-piercing process can be problematic when used with higher-strength aluminum alloys, which are much less ductile and so elongate less when penetrated, he stated. “That means you have to apply high pressure, which can create micro-cracks that affect the quality of the joint.”

“There’s a lot of international research in the piercing fastener area going on right now, but exactly how to design a cost-effective process to mitigate that problem is not clear.” Stress corrosion cracking is another issue that is under wide investigation, Feng noted.

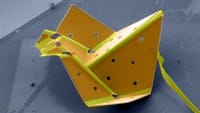

Flow drill screws enable assembly in limited-access areas. FDS flow drill screws produced by the German firm EJOT Industrial Fasteners have been used by Audi for years to build its aluminum-bodied A8 and TT cars. EJOT licensee, Semblex Corp. of Elmhurst, IL, supplies Ford with the specialized fasteners. Several other auto manufacturers are now evaluating the method for use on their future aluminum car structures. Another maker of flow drill screws is the German company Arnold Umformtechnik.

According to Lawrence Claus, a consultant for EJOT, flow drill screws are finely engineered piercing fasteners that “self-extrude” as they enter the metal being joined. The screw is rotated at high-speed during application so the sharp tip heats and pushes aside the workpiece metal. The hot, ductile metal flows to the sides of the hole where it cools to form a columnar jacket that the screw threads engage as the fastener sinks in, forming a strong mechanical joint.

Structural adhesives

The other major joining method used to assemble aluminum cars is super glue — structural adhesives. The substitution of adhesives for welds, rivets, screws, and bolts over recent decades has been so gradual it has mostly remained out of view. But it is gaining popularity in response to tough fuel-economy regulations, benefiting suppliers including Dow Automotive, H.B. Fuller, Henkel, L&L Corp., and 3M. About 27 lb (12 kg) of epoxy, urethane, and acrylic adhesives go into the typical car today, up from 18 lb (8.2 kg) a decade ago, according to ChemQuest Group, a Cincinnati, OH, consulting firm.

Adhesives can stiffen auto bodies so they won’t wobble or feel flimsy. They can damp noise and replace rivets or welds where they would show. Glue improves crash safety, durability, driving, and handling characteristics.

Another key technology for Ford’s F-150 is Alcoa 951, a pre-treatment bonding material that significantly strengthens the adhesive bonds between aluminum substrates. Alcoa 951 creates a bond that is nine times more durable than titanium-zirconium applications, according the Pittsburgh, PA-based company. When the coating is applied, its organic components link up with aluminum oxides on the surface. The molecules chemically bind the oxide to one end and the adhesive to the other, creating a strong chain. The surface treatment — ultra-thin and essentially transparent to downstream processes — has been licensed for general use on the F-150 program.

Dissimilar metals joining

Digital design models of future high-volume production cars often conclude that using different structural materials is the best way to cut costs, ONRL’s Feng noted, “but right now we do not have a lot of good options for joining dissimilar metals. The technical challenge has become a top research priority.”

Resistance spot welding doesn’t work well because aluminum has a much lower melting point than steel,” said Feng. “It has what we call metallurgical incompatibility.” He noted that “there’s a lot of international research in Europe, China, and Japan on various forms of solid-state weld-riveting. Most are focusing on non-melting processes.”

“Friction stir welding,” he continued, “is getting considerable attention for dissimilar metals joining — by Mazda, for example.” The friction stir technique uses a tool to mechanically mix the two metals without heating them to their melting points; instead, they are softened just enough to allow applied pressure to produce a metallurgical bond.

Friction-bit joining is another approach. It is based on a small, driven bit that creates a solid-state joint between metals both by cutting and by friction — something like a friction rivet. The U.S. Department of Energy is funding a four-year research effort to develop this technology by a consortium that includes ORNL, Brigham Young University, Ohio State University, and car companies.

Dissimilar metal joints, ones that connect different metals or that use a fastener that is of a different metal, always pose the risk of galvanic corrosion, said Ford’s Friedman: “We apply special barrier coatings and adhesives. The e-coated frame is painted, and in areas exposed to wet conditions we incorporate another barrier by inserting barrier material in between the joint.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...