Aluminum Prepares for Its Next Big Leap

Ford’s F-Series blockbuster was just the beginning. New Micromill processes now in pilot phase aim to bring vastly stronger and more formable and recyclable light-alloy materials at higher capacity, says Alcoa’s Mike Murphy.

Mike Murphy will never forget the day in 2011 at Ford World Headquarters when the aluminum industry won its biggest automotive prize: the blockbuster deal to supply the new aluminum-intensive F-Series trucks. Murphy stood nearby while his boss, Alcoa CEO Klaus Kleinfeld, co-signed the supply contract along with Ford CEO Alan Mulally.

“Everyone there recognized the historic event that was taking place that day,” Murphy, who is Alcoa’s VP Commercial Global Automotive, recalled. “And when the signatures were finished, we laughed when we saw what Mulally had written next to his name: ‘Have fun!’”

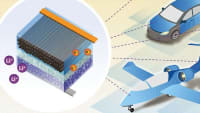

That advice was hardly whimsical for Alcoa, which has created over 90% of the aluminum alloys used in commercial airliners and helped Audi pioneer aluminum body structures 20 years ago, but has never had to deliver product at Ford’s staggering annual volumes and 60-jobs-per-hour rate. Having been engaged with Ford on the F-Series project since 2009, however, Murphy’s team was already working up contingencies for even higher-volume scenarios.

“We evaluated very carefully whether we could commit to sheet capacity beyond the Ford levels, should demand arise. And at a high level the answer is yes, without apprehension,” Murphy told Automotive Engineering. “For Alcoa, we’ve made it clear that if that additional business were to occur, the next significant investment would be a micromill-based investment.”

Micromill in Alcoa parlance is spelled with a capital M. It’s a major leap forward in many ways from traditional aluminum-sheet manufacturing, which requires a lot of floor space and is extremely capital intensive. By comparison, the Micromill is a continuous-rolling process that requires about 25% of the floor space of a conventional mill.

“We go from molten metal in the furnace, rapidly cooled, and immediately the metal comes out of the furnace in sheet form,” Murphy explained. “Then it goes into a hot mill where it’s rolled to gauge and rolled up into a coil. That’s it. Then you’ve got the downstream [heat-treat] process. But what the conventional mill does in about 20 days, the Micromill does in about 20 minutes.”

The innovation’s in the process. The microstructure of the aluminum sheet is entirely different than that of a direct-cast (DC) product, Murphy said, with significantly greater performance attributes.

“The product is 40% more formable than the traditional alloys and 30% stronger, which we think will make it highly competitive with the current aluminum-sheet products including our own. It meets automotive surface-quality standards. But more importantly, we think it has potential to even more rapidly displace steel in certain parts.” Alcoa claims that automotive parts made with its Micromill material will be twice as formable and 30% lighter than those made from high-strength steel.

The Micromill processing technology is flexible, enabling plants to transition between rolled products for automotive, industrial, and packaging markets. Murphy said Alcoa has completed customer-product trials at its recently announced Micromill pilot operation near San Antonio and is in the process of qualifying the material for next-generation automotive platforms.

A 6000 alloy to replace 5000 series?

The Micromill can make virtually any sheet product including automotive 5000- and 6000-series alloys. “Currently we’re introducing samples to customers, in applications on parts that are hard to form such as door and liftgate inners,” Murphy noted. “We’re asking them to use it for something they wouldn’t think they could use it for. Three to six months from now we’ll have a lot of feedback. But the preliminary responses have been very encouraging.”

The material’s higher strength attribute means it can be downgauged by up to 30% from a currently-used steel grade, which means a lighter-weight component or assembly.

While the 5000- and 6000-series are automotive’s aluminum workhorse alloys, Ford body structure engineers specified some tailoring of the material’s performance characteristics to the F-Series applications. The game-changer was Alcoa’s A951 surface treatment (also licensed to other companies) that gave Ford the assurance that the trucks will meet stringent durability requirements.

“We’ll prove the Micromill is a different animal in terms of heat-treat, too,” Murphy said without further detail. “We think 6000 series, which is heat-treatable, will continue to be the workhorse, but with the Micromill we’ll be able to provide unique, application-specific variations of 6000.

“Secondly, our customers source the non-heat-treatable 5000 series typically for its forming characteristics as well as its strength attributes — for use in door, liftgate, and sliding-door inners. Now imagine a product in the 6000 family,” he hinted, “with even better formability than 5000.”

The new alloy Murphy indicated is in development won’t have to be segregated, post-production, to achieve a maximum scrap value. For F-Series, Ford had to invest in a closed-loop process that segregates 5000 and 6000 material for post-production recycling which returns the material to the same engineering specification as the original. Most 5000- and 6000-series scrap in automotive stamping plants currently gets co-mingled and typically ends up in castings.

Facing the mixed-material future

Because the Micromill layout is relatively compact, Alcoa’s strategy is to locate it in close JIT proximity to the assembly plant it will serve. One key requirement, however, is a supply of molten metal. “Ideally the solution is to put the mill next to a smelter,” Murphy explained. “Our long-term vision is to locate next to the assembly plant where the coil goes out our door, into the assembly plant where it’s stamped then goes right into the body shop.”

But despite their excitement for the Micromill’s potential, Alcoa planners accept the reality that the majority of automotive programs will continue to be based on a mixed-material strategy. “The ability to bond or weld dissimilar metals will be more important in the future,” Murphy said.

“I anticipate the future for us will be tweaked alloys and tempers, but all vehicles are not going to be AIVs [aluminum-intensive vehicles]. So we’re absolutely aligned with multi-material designs,” he said. “For example, it’s very critical for us to understand how aluminum interacts with steel and carbon fiber,” part of a collaborative research project Alcoa is involved in with the U.S. Department of Energy.

And what of the super-tough 7000-series alloys that some body engineers speak of in reverent tones? “It [7000] utilizes our aerospace knowledge,” Murphy said. “It’s difficult to form but significantly higher strength than current materials. And although it probably is not our vision that cars of the future will be 7000-series intensive, we think it has a place for specific components.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...