The Economics of Materials Selection

Cost per pound of reduced vehicle mass is helping to drive innovation in steel, aluminum and carbon composites.

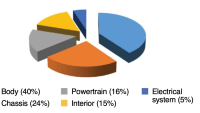

"We’ve entered an era where true weight reductions in vehicles are occurring,” noted Dr. Alan Taub, professor of Material Science & Engineering at the University of Michigan. “There is no new vehicle launch that doesn’t talk about a 5-10 percent reduction in curb weight because it’s now clearly a part of fuel economy. And while the gains are still coming from powertrain improvements and the introduction of partial and full electrification, about 15 percent of fuel-economy improvements today come from vehicle weight reduction.”

His rule of thumb: Decreasing vehicle weight by 10% yields a 6% improvement in fuel economy.

At the 2019 Society of Plastics Engineers’ ANTEC conference, Dr. Taub, formerly GM’s head of R&D, presented a review of the three major materials groups—steel, aluminum, and composites—that he expects will predominate in vehicle body structures (increasingly in a mixed-materials play) going forward.

“If you’re chief engineer of a new-vehicle program, your job is to deliver the targeted fuel economy at the lowest possible cost,” he noted. “You follow a plot that says, ‘dollars per miles-per-gallon improvement.’ Depending on the OEM, that cost is about $2 to $2.50 per pound saved. Materials suppliers who can deliver that are going to get on the program.”

STEEL: The biggest dynamic in vehicle body materials planning today is the replacement of low-carbon steels with a growing portfolio of high-strength steel grades. Steel remains the Big Kahuna in vehicle structures, and the new grades deliver significantly greater strength (and thus better crash safety) than previous grades, with reduced mass, for a minimum of about $.50 per pound — "very cost effective,” Taub said.

Not long ago, body engineers thought 300 MPa [megapascals, a measure of tensile strength] was the limit for stamping steels. Today, stamping 800 MPa material, or even higher grades, is common. These ultra-high-strength or advanced high strength steel (UHSS and AHSS) grades offer greater strength enabling reduced weight — the stronger the material, the thinner it can be made for the same application. But the new grades above 1,000 MPa are difficult to stamp at room temperature. They require hot forming (also known as press hardening) — a complex operation that heats, shapes, and quenches the sheet while it’s in the die.

Press-hardening adds cost, but those grades are “still well below that $2.00-$3.00 per pound saved threshold,” Dr. Taub explained. He said the steel industry is developing 1,200 to 1,400 MPa products that are sufficiently ductile to be stamped at room temperature—with even stronger grades to follow.

“The high-strength steels we used to say were limited to 10-to-15 percent weight reduction will soon be capable of delivering up to 25 percent reductions,” he told the plastics engineers.

ALUMINUM: Because it’s not as ductile as steel, manufacturers can’t yet stamp aluminum sheet in the same extreme shapes as steel offers, Dr. Taub noted. But the industry “has gotten much better at forming parts out of aluminum. And it has solved the joining problem that put it at a disadvantage to steel spot-welding,” by adopting mechanical fastening and even new processes to spot-weld aluminum to steel.

With a density that is 2.5 times less than comparable steel, “aluminum has quickly become the weight-saving material of choice for closures, where it’s now being delivered at below $2.00 per pound saved,” Dr. Taub said.

But the fundamentally higher cost of making aluminum, due to the energy-intensive nature of refining bauxite, continues to make it a premium-priced play. In addition, the industry is beginning to reach the limit of its rolling-mill capacity—which may cause restrictions of material availability. According to Dr. Taub, “OEMs developing new vehicles with extra aluminum content must team up with one of the aluminum companies to build up that capacity in rolling.”

Those challenges aside, F-150 is on track for record sales, “and more OEMs are talking about additional aluminum content on vehicles,” Dr. Taub reported.

COMPOSITES: “So far, we know that the lightest-weight vehicle we can make is in carbon-fiber composite,” stated Dr. Taub, who is also senior technical advisor at the American Lightweight Materials Manufacturing Innovation Institute.

Making carbon fiber the material of choice for automotive structures faces numerous challenges. While many OEMs and Tier 1s are committed to working on it in low volume projects, BMW has walked away from its multi-million-dollar venture with SGL Carbon that spawned BMW’s novel i3 and i8 models—built on a supply chain that stretched from Germany all the way to northern Washington state.

“I am a believer that the end game in automotive primary body and chassis structure will contain significant carbon-fiber composites — it’s the material that can give us the most weight savings,” Dr. Taub said.

So, what’s it going to take to get there?

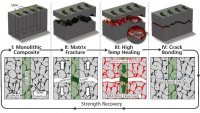

First, carbon fiber must meet all impact standards—difficult for a super-stiff material that fractures under extreme impact rather than deforms like metals. “The good news is we’ve learned how to model it, and it now gives higher specific energy absorption,” he noted.

Then there’s the molding time to produce a part—still a nagging issue. According to Dr. Taub, composites researchers are working to get the largest part of the vehicle — the floorpan—down to less than 1 minute in the mold. “We’ve reduced that process from eight minutes seven years ago to about four minutes today, and the one-minute cycle is starting to look possible,” he told the SPE audience. “We’re still looking for that instant cure.”

The next technology shift likely will be to thermoplastic-resin carbon fiber composites that offer the same structural properties with much-reduced molding time.

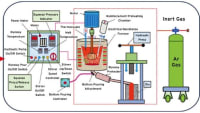

Cost of the material’s precursor, as well as the process used to convert it into high-strength carbon fiber, are also the focus of materials scientists and process engineers. “There is lots of work going on to reduce costs in all areas — we’ve gone from $20 per pound to $10 per pound, and we’re moving toward $7,” Dr. Taub reports. He adds that closed-loop recycling for the material still needs to be established: “That’s the end game for composites. I believe they can win eventually on every other single item including cost and cycle time.”

The mobility industry has migrated from single-material-intensive vehicles (i.e., F-150) to the concept of right material, produced the right way and engineered into the right part of the vehicle. “Now, the design engineers can go into ANSYS or whatever tool they use and select their material of choice; the component engineers can make that part in complex shapes, while the manufacturing engineers handle the multiplicity of materials and forms,” Dr. Taub noted. “And the joining engineers? They’re the ones everybody is investing in.”

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance