Innovations for Lightweighting: Magna and Ford test carbon-fiber subframes

Tough fuel-economy bogies for 2021 and beyond are driving new approaches to materials use, as seen in these examples.

Carbon-fiber reinforced polymers are the yin and yang of automotive lightweighting. Their strength-to-weight ratio handily outperforms chrome-moly steel, heat-treated aluminum alloys and magnesium. The aerospace industry gobbles the strong, stiff and light composite for use in wing spars and plans to use it in entire primary structures (SpaceX’s next-gen heavy launch vehicle) in the future. But CFRP’s slow part-to-part cycle rates, relatively complex processing and unique failure modes have kept it from being a player in volumes of more than 150,000 units per year for automotive structural applications.

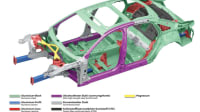

Magna International and Ford Motor Co. believe CFRP holds promise in vehicle structures—specifically front and rear subframes. The companies are preparing to test a batch of prototype CFRP front subframes they developed collaboratively over the last two years. The prototype cradle, now being installed in Ford unibody development mules, is 34% lighter than a comparable steel fabrication typically used in passenger vehicles. It is 16% lighter than a comparable aluminum fabrication.

Comprising two main pieces—upper and lower moldings bonded and riveted together, along with four overmolded body-mount bushings—the CFRP cradle replaces 45 stamped-and-joined components in a benchmarked steel subframe. The bill of materials is reduced by 87%.

“Ford challenged us with this concept, which is a continuation of our collaboration on the Multi-Materials Lightweight Vehicle project,” explained Grahame Burrow, President, Magna Exteriors. His team and Magna’s Cosma chassis group worked closely with a Ford Research and Advanced Engineering team under Mike Whitens, in the subframe design. Magna orchestrated tooling and unveiled the first ‘shots’ at the 2017 JEC World composites show.

Burrow expects subframe testing to proceed through 4Q17 when “real results from real vehicles” will be available. From an FEA perspective, “all the tests to date have performed at or better than a steel subframe,” noted Brian Krull, Magna Exteriors’ Global Director of Innovation. “We’re hoping to see those same results in physical testing.” He described the material’s NVH performance as “excellent.”

Beyond the initial CAE work, the vehicle-level phase will evaluate corrosion, stone chipping and bolt-load retention and crash performance. The project team also will develop a recommended design, manufacturing and assembly process with the experience gained during the prototype build and subsequent testing.

Subframe “perfect” for CFRP

While Magna has extensive experience in carbon-fiber components for production, including the grille-opening reinforcement for Ford’s Mustang Shelby Cobra GT500 and the hood of Cadillac’s V-series sedans, the subframe project is the largest and most complex CFRP component yet developed, according to Burrow.

CFRP has for years tantalized chassis engineers looking to take mass out of vehicle frame structures. In the late 1990s, General Motors enlisted lightweight-aircraft pioneer Burt Rutan to co-develop a CFRP ladder frame aimed at full-size SUVs and Corvette. Interviewed by the author at the time, GM R&D boss Larry Burns said the project’s cost targeting ratio was $20 per pound removed, compared with a steel frame. The prototype CFRP frame reduced mass by 200 lb (91 kg) but steel remained the industry’s chassis and subframe material of choice.

The sheet-molding compound (SMC) that is used in the Ford CFRP project is a new material that was developed by Magna specifically for structural applications, according to Andrew Swikoski, Global Product Line Director, Lightweight Composites.

“The front subframe was a perfect application for it,” he told Automotive Engineering, adding that two materials were developed for the subframe: one is a chopped-carbon-fiber SMC and the other is a continuous fiber that is strategically placed in the parts that need a boost in properties. “Both materials were under development and Ford was cognizant of that; it was one reason they brought us into this development project,” Swikoski said.

Magna purchases the carbon fiber from Zoltek, part of the Toray Group. It then compounds the material in house. Swikoski noted that CFRP has directional-strength properties that rely on the orientation and proportion of the fibers relative to the polymer. Typically, chopped carbon fiber’s potential strength is limited because the material is scattered within the final part. Continuous carbon fiber offers greater potential strength because the thousands of carbon fibers are bundled in long strands.

Scaling for high volumes

According to Burrow and Krull, the two-piece prototype cradle could potentially evolve into a single-piece molding in future development.

“Given a clean-sheet approach, if we could be alongside vehicle architects from scratch, there could be opportunity to do this cradle in a single component,” Burrow said.

“What you don’t see underneath the close-out panels are a significant number of ribs underneath to handle the load path. This was one of the great achievements in this project, the amount of ribbing that’s integral to the component,” Krull noted. “Based on the structural ribs, I think a single piece is very feasible.”

The Magna engineers admitted that driving cost out of CFRP components has taken on greater urgency, driven by the more stringent global regulations for vehicle emissions. Their company’s manufacturing expertise is helping the subframe development teams innovate solutions on the plant side.

“We were working under the constraints of the existing MMLV; the new subframe had to fit that vehicle,” Krull explained. “If we had a clean-sheet approach we could potentially bring in some new innovations that would drive ease of assembly moving forward.”

Materials experts note that compression molding helps speed manufacture of the CFRP workpiece. A two-piece (male/female) mold is pressed together, with the CF fabric and resin between the two. BMW has claimed its production methods for the CFRP-intense i3 and i8 cars enable a new part to be cycled every 80 seconds. The process, however, is a high-cost investment due to high-precision CNC machining used to make the molds.

“Our target cycle time for this technology on this type of product is the range of three minutes,” Krull asserted. “It depends on part complexity and size. Cure time depends on thickness. We have quite a bit of automation we can throw at this for the loading and unloading. That’s what Magna is really good at.

“We can scale this for mass production—100,000 to 200,000 vehicles per year is certainly in the realm of possible,” he opined. “That’s exciting for us; it takes this material out of the ‘niche’ area.”

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance