Microbullets Reveal Material Strengths

In the macro world, it’s easy to see what happens when a bullet hits an object. But what happens at the nanoscale with very tiny bullets? A Rice University lab, in collaboration with researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and its Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, decided to find out by creating the nanoscale target materials, the microscale ammo and even the method for firing them. In the process, they gathered a surprising amount of information about how materials called block copolymers dissipate the strain of sudden impact.

The goal of the researchers is to find novel ways to make materials more impervious to deformation or failure for stronger and lighter body armor, jet engine turbine blades for aircraft, and for cladding to protect spacecraft and satellites from micrometeorites and space junk.

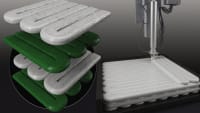

The researchers, led by Rice materials scientist Ned Thomas and Rice research scientist and lead author Jae-Hwang Lee, were inspired by their observations in macroscopic ballistic tests in which a complex multiblock copolymer polyurethane material showed the ability to not only stop a 9 mm bullet but also seal the entryway behind it.

“The polymer has actually arrested the bullet and sealed it,” Thomas said, holding a hockey puck-sized piece of clear plastic with three bullets firmly embedded. “There’s no macroscopic damage; the material hasn’t failed; it hasn’t cracked. You can still see through it. This would be a great ballistic windshield material. “We want to find out why this polyurethane works the way it does. Theoretically, no one understood why this particular kind of material – which has nanoscale features of glassy and rubbery domains – would be so good at dissipating energy.”

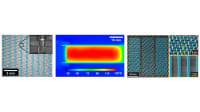

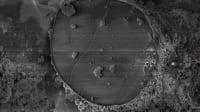

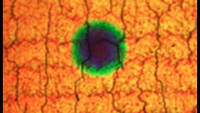

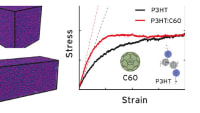

One problem, Thomas said, is that cutting the polymer to analyze it on the nanoscale “would take days.” The researchers sought a model material that would react similarly at the nanoscale and could be analyzed much faster. They found one in a polystyrene-polydimethylsiloxane diblock-copolymer. The material self-assembles into alternating 20-nanometer layers of glassy and rubbery polymers. Under a scanning electron microscope, it looks like corduroy; after the test, the disruption pattern from impact can be clearly seen.

The results showed several expected deformation mechanisms and the unexpected result that for sufficiently high velocities, the layered material melted into a homogeneous liquid that seemed to help arrest the projectile and, like the polymer, seal its entry path. The copolymer also behaved differently depending on where the spheres hit. The material showed the best ability to dissipate the energy of impact when spheres were fired perpendicular to the layers, Thomas said.

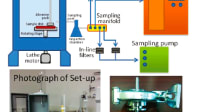

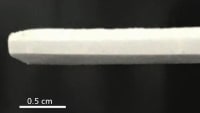

Testing their ideas took special equipment. The research team came up with a miniaturized test method, dubbed the laser-induced projectile impact test (LIPIT), that uses a laser pulse to fire glass spheres about 3 microns in diameter. The spheres sit on one side of a thin absorbing film facing the target. When a pulse hits the film, the energy causes it to vaporize and the spheres to fly off, hitting speeds between .5 and 5 kilometers per second. Since the kinetic energy scales with velocity squared, the factor of 10 in speed translates to a factor of 100 in impact energy, Thomas said.

Lee calculated the impact in real-world terms. The spheres strike their target 2,000 times faster than an apple falling one meter hits the ground, but with a million times less force. However, because the sphere’s impact area is so concentrated, the impact energy is more than 760 times greater. That leaves a mark, he said.

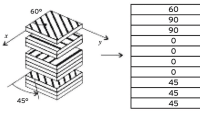

The team tested their materials in two ways: horizontally, with the impact perpendicular to the micro grain, and vertically, straight into the layered edges. They found the horizontal material best at stopping projectiles, perhaps because the layers reflect part of the incident shock wave. Beyond the melt zone in front of the projectile, the layers showed the ability to deform without breaking, which led to improved energy absorption.

“After the impact we can go in and cross-section the structure and see how deep the bullet got, and see what happened to these nice parallel layers,” Thomas said. “They tell the story of the evolution of penetration of the projectile and help us understand what mechanisms, at the nanoscale, may be taking place in order for this to be such a great, high-performance, lightweight protection material.”

Thomas would like to extend LIPIT testing to other lightweight, nanostructured materials like boron nitride, carbon nanotube-reinforced composites and graphite and graphene-based materials. The ultimate goal, he said, is to accelerate the design of metamaterials with precise control of their nano- and microstructures for a variety of applications.

View the video below.

Transcript

00:00:01 well this particular piece of polymer is a polyurethane and it's interesting because it's got three 9mm slugs that have been shot into the backside and have been arrested inside that polyurethane and there's no macroscopic damage the material hasn't failed it hasn't cracked even you can still see

00:00:23 through it so this be a great ballistic windshield material and what we wanted to do is find out why this particular poly Ane works the way it does experimentally it works and theoretically no one understood why this particular kind of material which actually has nanoscale features of glassy and rubbery domains uh would be so good at dissipating energy what we

00:00:45 did was to work with model material a polystyrene polymethyl Cy oxane polymer which has glassy and rubbery components just like the polyurethane does but we can uh control its micro structure at the Nano scale and form parallel layers that are only 20 NM a piece thick and these things form a parallel stack and it's a sort of an ideal starting morphology and then instead of shooting

00:01:12 a 9mm slug into it we decided to uh miniaturize the bullet if you like so we're shooting a silic sphere that's only 3 microns in diameter human hair is about 50 microns in diameter so this is like more than a tenth smaller than the diameter of a human hairir so we have sort of a micro bullet that we're shooting into into a nanoscale structure and then after the impact of the bullet

00:01:34 we can go in and cross-section the structure see how far and how deep uh the bullet gut and in fact see what happened to these nice parallel layers of glassy and rubbery domains they they sort of tell the story of the uh evolution of the penetration of the projectile and help us understand on at the nanoscale What mechanisms are taking place in the material in order for this

00:01:55 thing to be such a great uh high- performing lightweight uh ballistic prote material in the microscopic image you are looking at the actual uh projectile projectile is tiny tiny tiny so each side is about 3.7 Micron diameter silica bead so on the microscope you can aim the projectile and then after aiming we can shut the laser pulse by the laser pulse the

00:02:22 projectile can move toward the sample the goals of the research is to be able to develop met better materials lightweight materials for protection and of course body armor for soldiers would be one um turns out that the turbine blades on engines also have very highspeed impacts from say hail or sand that gets into a a jet turbine engine uh and satellites uh up orbiting the Earth

00:02:47 uh there are micr meteorites up there very small projectiles going very fast and occasionally these impact the satellite and poke holes in it so being able to develop lightweight materials that have Superior resistance to these sort of uh I would say extreme uh Dynamic conditions where the velocities are uh kilometers per second lightweight is is

00:03:08 really a big deal if this was a piece of Steel uh it wouldn't perform as as well as the polyurethane and it would be seven times heavier

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance