Leading the Attack on Engine Pumping Losses

Cylinder deactivation delivers real-world fuel economy gains, helping vehicles to meet and exceed their sticker numbers. That’s why the downsized/boosted guys now want it on their engines.

Powertrain engineers talk about the advantage of having more “knobs to turn” — technologies that work synergistically to reduce fuel consumption and help increase vehicle efficiency. For the past decade, direct injection and turbocharging have been a popular “knob” for enabling downsized gasoline engines to perform like larger-displacement ones while consuming less fuel. Meanwhile, cylinder deactivation has helped big engines deliver surprisingly good economy, while keeping deep reserves of torque available when the driver’s right foot demands it.

Until recently, the technologies have mostly remained separate in the powertrain planners’ toolbox. Their adoption has sometimes raised debate as to which is the most effective in terms of real-world fuel economy, unit cost, and performance. But the stringent CO2 emission demands of Euro6, U.S. 2025 CAFE, and new Asian regulations have engineers searching for solutions that leverage both.

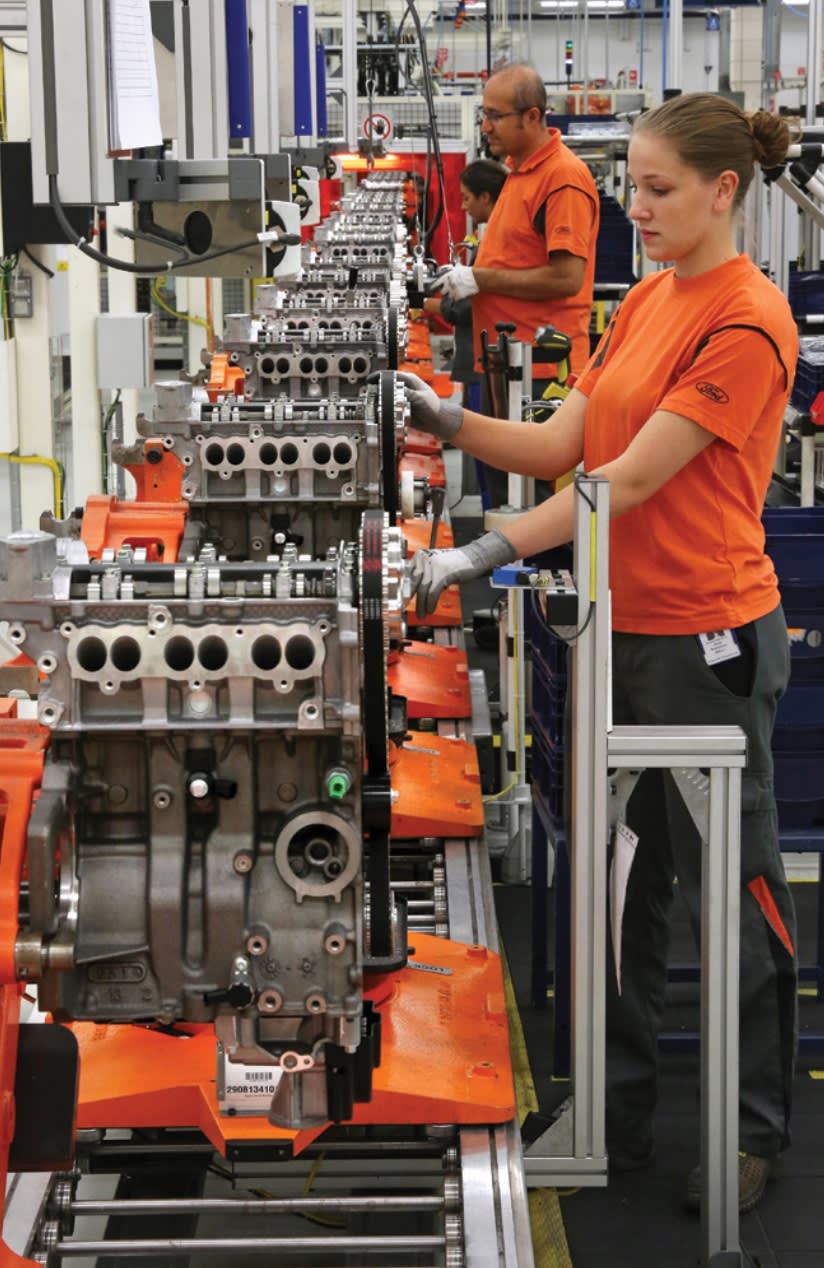

Ford, which has staunchly built its powertrain portfolio around the EcoBoost strategy, appears poised to jump into the cylinder-deactivation race where GM, Honda, FCA, Mercedes, and VW Group are already running. At the 2015 Vienna Motor Symposium, Ford’s Global Powertrain R&D Director, Dr. Andreas Schamel, announced two approaches to cylinder deactivation focusing on the 1.0-L EcoBoost triple, effectively turning it into a 666-cm3 twin. Schamel’s team, which collaborated with Schaeffler Group on the project, concluded that “even highly downsized engines can benefit from a cylinder deactivation strategy, with fuel consumption reduction gained in various global drive cycles — and under real conditions.”

Volkswagen has at least a four-year lead on Ford in this segment. In 2012 it introduced the first high-volume turbocharged engine with cylinder deactivation. The 1.4-L TSI shuts off two of its four cylinders under low- to mid-load (1400 to 4000 rpm) situations. On the NEDC driving cycle, VW’s complex Active Cylinder Technology reduces the 1.4 TSI’s fuel consumption by 0.4 L/100 km — a CO2 equivalent of 8 g/km — with potential for 1 L/km reduction in certain driving conditions.

“The single biggest thing you can do to an engine to make it more efficient is reduce its pumping work — and cylinder deactivation is a huge knob for us to turn here,” explained Jordan Lee, Global Chief Engineer and Program Manager for Small Block Engines at GM.

Dedicated technology enablers emerge

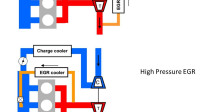

Pumping work, and the efficiency losses it incurs, is the effort required to move air into and out of the cylinders, with the throttle plate being a major restriction. “It’s like trying to run a marathon while breathing through a straw. Take the straw out and your efficiency improves,” Lee said.

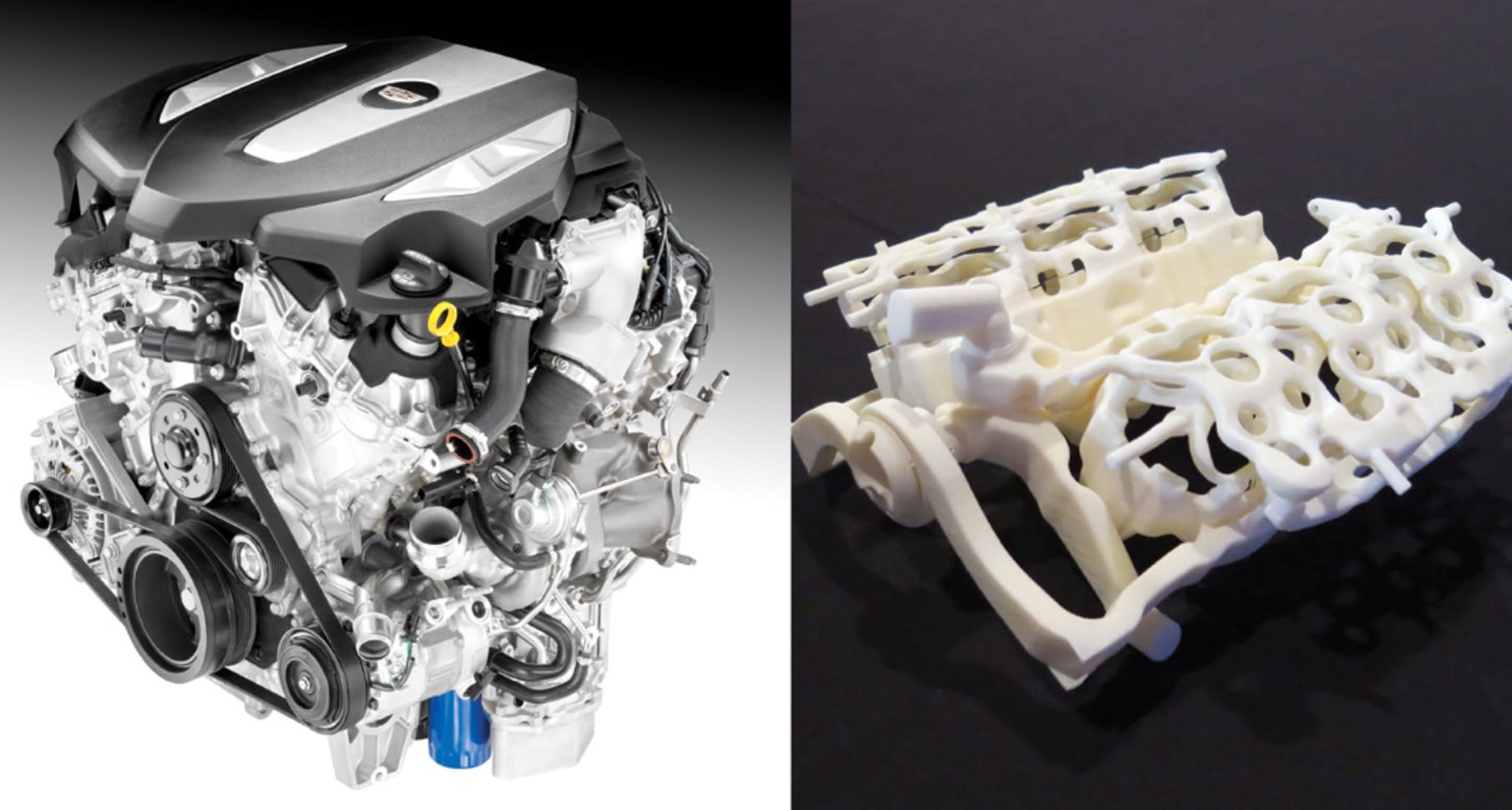

GM, with the most experience and sheer volume in this field, has refined its Active Fuel Management (AFM) system to be a key factor in raising the real-world fuel efficiency of its full-size trucks and Corvette. At the vehicle level with the Gen5 V8s, customers have seen up to 15% fuel economy gains in trucks, and up to 22% on the Corvette, compared to non-AFM engines. The OHV V6 and V8s using AFM are joined by an all-new DOHC V6 family — the 2016 3.0-L twin turbo (LGW) and 3.6-L naturally aspirated (LFX) DOHC V6s — that were designed from a clean sheet to optimize AFM operation.

“The V6 combustion systems were developed so we could run as much as possible in 4-cylinder mode; the torque available in 4-cylinder mode is what drives how much AFM you can use,” noted Ameer Haider, Assistant Chief Engineer. “We added a cam carrier between the cylinder head and block and incorporated most of the hydraulics in that package. That gave us a very compact solution and kept the hydraulics and the lines at the shortest possible length, for faster response time.”

There’s also a variable-displacement oil pump, similar to that on the Gen5 V8. “Consistency of oil pressure, temperature, and viscosity are critical for cylinder deactivation, as is system voltage,” Haider noted. Some GM owners’ blogs have reported excessive oil consumption on earlier Gen4 AFM engines; Lee noted this is a concern “because when the cylinder’s deactivated there’s a vacuum in that cylinder and oil splashes up from underneath and can get sucked past the piston rings. With Gen4’s we were a little nervous about that.” Improvements to the Gen5 family, including the new oil pump, have eliminated oil-consumption concerns, he asserted. Honda also has experienced excessive oil-consumption issues with its V6 Variable Cylinder Management system.

GM’s new AFM for DOHC architectures uses a Type 2 valvetrain with Eaton roller rocker mechanisms. Minor improvements in the lifter technology and overall system robustness were made in the Gen4 to Gen5 evolution, according to Wai Nguyen, a GM valvetrain design engineer. And systems suppliers are responding with innovation to the increase in global engine programs slated for cylinder-deactivation.

Interest in 3-cylinder engines, for example, influenced Eaton’s development of Dynamic Cylinder Deactivation (D-CDA), designed for engines with an odd number of cylinders using Type 2 valvetrains. In a triple, the D-CDA mechanism deactivates each cylinder every second combustion cycle, effectively creating a 1.5-cylinder engine and avoiding the vibration and irregular torque characteristics that triples suffer when deactivated to twin-cylinder operation. Eaton claims the D-CDA enables expanded deactivation bandwidths, up to 50% of engine load and 4000 rpm.

9 ms response times coming

Engineers stress the importance of matching engine displacement to vehicle mass at the outset of a new program. This development tenet will certainly influence Ford’s 1.0-L cylinder-deactivation applications as it has VW’s and the others. The larger and heavier the vehicle, the more frequently a smaller boosted engine will run in boost mode where it uses a lot more fuel. That was one of the drivers behind Ford’s investment in an aluminum-intensive truck platform, and it’s a reason why some F-150 EcoBoost V6 customers have groused in owners blogs about their light-metal trucks’ real-world fuel economy vs. the sticker numbers.

“The downsized boosted engines can get good fuel economy in performance applications where they predominantly run lightly loaded,” explained Rick Davis, GM’s Global Spark Ignition Combustion Technical Specialist. “They can do a good job in reducing pumping work because of their being downsized. But as soon as you try to run high loads — particularly mountain driving or trailer towing — the efficiency goes away. Once you get into the boost regime and face knock limitations and compression-ratio limitations, the efficiency tradeoff is not there.”

Davis said one useful way to overlay the technologies is to compare fuel consumption on an equivalent-torque basis. He acknowledges that at very light loads the downsized boosted unit shows benefits in fuel economy, but at higher load regimes the advantage disappears. Adds Lee (who admits the F-Series with the twin-turbo 2.7 L is fun to drive): “You have to really train yourself to drive it in ‘fuel economy mode’ in order to get good economy.”

From an overall vehicle-systems standpoint, a nice feature of an engine with cylinder deactivation is that its fuel economy isn’t necessarily optimized with the smallest displacement. A larger-displacement engine with deactivation can offer superior economy and performance because it can operate in half-cylinder mode a higher percentage of the time. And in terms of vehicle integration, it’s important to design the platform with cylinder deactivation in mind so that vibration modes and intake and exhaust noises are dealt with at their root.

And the next frontier for cylinder deactivation? New control strategies such as that being developed by Tula Technologies offer great potential (see sidebar). System response time will continue to improve, noted Nguyen — “It’s critical when you try to push the envelope in how much you want to operate in AFM mode,” he said. Currently GM’s solenoids can respond to AFM signals in 20 ms; the next-generation system now in development will feature 9-ms response time.

“By making the solenoids’ reaction even faster, we can go into and out of the different operating modes even more quickly,” observed GM Senior Staff Engineer Jeff Hodson. Added Jordan Lee: “We can’t divulge all the new technology but I can say we’re looking at expanding the operating range of AFM significantly.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...