Machine Learning Unlocks Secrets to Advanced Alloys

An MIT team uses computer models to measure atomic patterns in metals, essential for designing custom materials for use in aerospace, biomedicine, electronics, and more.

The concept of short-range order (SRO) — the arrangement of atoms over small distances — in metallic alloys has been underexplored in materials science and engineering. But the past decade has seen renewed interest in quantifying it, since decoding SRO is a crucial step toward developing tailored high-performing alloys, such as stronger or heat-resistant materials.

Understanding how atoms arrange themselves is no easy task and must be verified using intensive lab experiments or computer simulations based on imperfect models. These hurdles have made it difficult to fully explore SRO in metallic alloys.

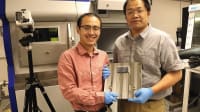

But Killian Sheriff and Yifan Cao, graduate students in MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering (DMSE), are using machine learning to quantify, atom-by-atom, the complex chemical arrangements that make up SRO. Under the supervision of Assistant Professor Rodrigo Freitas, and with the help of Assistant Professor Tess Smidt in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, their work was recently published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Interest in understanding SRO is linked to the excitement around advanced materials called high-entropy alloys, whose complex compositions give them superior properties.

Typically, materials scientists develop alloys by using one element as a base and adding small quantities of other elements to enhance specific properties. The addition of chromium to nickel, for example, makes the resulting metal more resistant to corrosion.

Unlike most traditional alloys, high-entropy alloys have several elements, from three up to 20, in nearly equal proportions. This offers a vast design space. “It’s like you’re making a recipe with a lot more ingredients,” says Cao.

The goal is to use SRO as a “knob” to tailor material properties by mixing chemical elements in high-entropy alloys in unique ways. This approach has potential applications in industries such as aerospace, biomedicine, and electronics, driving the need to explore permutations and combinations of elements, Cao says.

A Two-Pronged Machine Learning Solution

To study SRO using machine learning, it helps to picture the crystal structure in high-entropy alloys as a connect-the-dots game in a coloring book, Cao says.

“You need to know the rules for connecting the dots to see the pattern.” And you need to capture the atomic interactions with a simulation that is big enough to fit the entire pattern.

First, understanding the rules meant reproducing the chemical bonds in high-entropy alloys. “There are small energy differences in chemical patterns that lead to differences in short-range order, and we didn’t have a good model to do that,” Freitas says. The model the team developed is the first building block in accurately quantifying SRO.

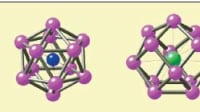

The second part of the challenge, ensuring that researchers get the whole picture, was more complex. High-entropy alloys can exhibit billions of chemical “motifs,” combinations of arrangements of atoms. Identifying these motifs from simulation data is difficult because they can appear in symmetrically equivalent forms — rotated, mirrored, or inverted. At first glance, they may look different but still contain the same chemical bonds.

The team solved this problem by employing 3D Euclidean neural networks. These advanced computational models allowed the researchers to identify chemical motifs from simulations of high-entropy materials with unprecedented detail, examining them atom-by-atom.

The final task was to quantify the SRO. Freitas used machine learning to evaluate the different chemical motifs and tag each with a number. When researchers want to quantify the SRO for a new material, they run it by the model, which sorts it in its database and spits out an answer.

The team also invested additional effort in making their motif identification framework more accessible. “We have this sheet of all possible permutations of [SRO] already set up, and we know what number each of them got through this machine learning process,” Freitas says. “So later, as we run into simulations, we can sort them out to tell us what that new SRO will look like.” The neural network easily recognizes symmetry operations and tags equivalent structures with the same number.

“If you had to compile all the symmetries yourself, it’s a lot of work. Machine learning organized this for us really quickly and in a way that was cheap enough that we could apply it in practice,” Freitas says.

This work was performed by researchers from MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering (DMSE). For more information, download the Technical Support Package (free white paper) below. ADTTSP-10242

This Brief includes a Technical Support Package (TSP).

Quantifying Chemical Short-range Order in Metallic Alloys

(reference ADTTSP-10242) is currently available for download from the TSP library.

Don't have an account?

Overview

This document discusses the characterization and quantification of short-range order (SRO) in complex concentrated alloys, particularly focusing on the limitations of traditional methods that rely on first nearest-neighbor Warren-Cowley (WC) parameters. The authors argue that these methods fail to capture the many-body nature of chemical bonds and the electronic nearsightedness in condensed systems, which necessitates a more comprehensive representation that includes (n + 1)-body terms, where n is the coordination number of the central atom.

The study introduces a motif-based approach that utilizes graph representations of local chemical environments and a message-passing algorithm to account for the connectivity among nearest neighbors. This method allows for a more nuanced understanding of how different atomic arrangements influence physical properties, as demonstrated through examples involving chromium (Cr) surrounded by nickel (Ni) and cobalt (Co) atoms. The authors highlight that even small variations in local motifs can lead to significant differences in properties such as local lattice distortion and probability density.

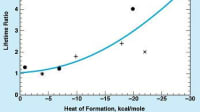

To quantify SRO, the document employs a generalized definition of entropy, specifically the Shannon entropy, to compare the probability distributions of motifs in thermally equilibrated systems versus random solid solutions. This approach reveals that certain motifs are significantly more common in equilibrium, indicating the presence of SRO. The authors emphasize the importance of evaluating spatial correlations among motifs to fully describe SRO, which is linked to thermodynamic principles.

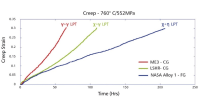

Additionally, the document discusses the characteristic length scale of chemical fluctuations, defined as the radial distance at which motifs become uncorrelated. This length scale is crucial for understanding the impact of SRO on material properties, particularly in high-entropy alloys. The findings suggest that as temperature increases, the fraction of atoms exhibiting short-range ordering decreases, reinforcing the need for simulations that accurately capture these effects.

Overall, the document presents a comprehensive framework for understanding and quantifying SRO in complex alloys, highlighting the interplay between local chemical motifs and macroscopic material properties. This research has significant implications for the design and optimization of advanced materials in various applications.

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance