Women in Vehicle Engineering

Females have made significant progress cracking the predominantly male domain of automotive engineering. They’re now chief engineers, VPs, even a CEO. But why are there still so few of them?

Cindy Hess rocketed through the Auburn University College of Engineering in just three years. Graduating as an electrical engineer in 1977, she turned down job offers from aerospace giants Boeing and General Dynamics to join Chrysler Electronics as its first-ever female engineer. In 1981, she was assigned to the automaker’s Highland Park, MI, complex.

“I was the sixth woman within a workforce of about 6000 engineers at Chrysler at the time,” she recalled. “And it’s incredible when I think about what we had to endure to do our jobs in those days.”

It wasn’t just the condescending and sexist overtones punctuating regular conversations that bothered the rookie Hess, who grew up among nine siblings, was treated as “one of the guys” during college, and eventually rose to Chrysler’s Vice President of Small Car Engineering and later, VP of Corporate Quality. For a 20-year-old female engineer during that era, the auto industry’s work environment could alternate between hostile and downright frightening.

“I’d often have to visit remote corners of the old buildings to pick up components for use in our prototype builds,” she said. “The parts cribs were located in a dimly lit area, and when I arrived, the men in charge would make a ‘whoop-whoop’ noise like animals. When I asked for my parts, they’d reply ‘Is that all you want, honey?’”

Their comments typically degenerated further, but Hess remained undaunted until the men ended the ritual, laughed, and handed over the requested items. “It still amazes me how anyone working for the same company as me could talk to me that way,” said Hess, now retired after a 30-year engineering and consulting career.

Two decades later, at Ford, MaryAnn Wright was prepared for a design review of a new Lincoln model developed by her team. Recently promoted to chief engineer of the program, Wright was ready to brief her boss, a Ford vice president, on the technical changes in each area of the car. She was particularly excited to report how they had collaborated with Jaguar, which Ford owned in the late 1990s.

“When he arrived, we walked toward the car and I began to tell him about its powertrain,” Wright recalled. After a few steps, the VP stopped, spun toward Wright, and looked her “up and down.” He then declared: “Girls get to talk about colors. They do not talk about powertrains,” and marched on ahead.

Wright, who is currently Vice President of Engineering and Product Development at Johnson Controls Power Solutions, stopped in her tracks. She was “literally floored” by the blatant disrespect shown to her by a top manager, particularly in front of colleagues who were nearby.

More recently, in 2013, a group of American auto writers was in Asia attending a new-vehicle reveal. The trip included a visit to the host company’s technical center where, in a meeting with engineering leaders, the U.S. group was served tea and snacks by a few conservatively dressed young women. One of them, it was later learned, was a graduate mechanical engineer. “This may be as far up the ladder as she’ll go here,” one of the company’s U.S. PR execs lamented privately.

16% and counting

In the 92 years since Marie Luhring joined Mack Truck as the first female automotive engineer in the U.S. and held similar distinction as a member of the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), women have faced countless hurdles in their quest for professional equality. Today a growing number of them are attaining leadership positions in what is still a heavily male-dominated field.

“It’s really exciting that there are now women at all levels of engineering management, where when I started 25 years ago, you’d only find us in the younger ranks,” observed Stacey DelVecchio, Vice President of Product Development and Technology at Caterpillar, and 2014 President of the Society of Women Engineers. “We’ve now got role models across the industry,” she noted.

The roster of female engineers who moved into top leadership positions before General Motors CEO Mary Barra’s groundbreaking 2014 promotion is comparatively modest but encouraging. In recent years, it includes Ford of Europe’s chief operating officer, Cummins Inc.’s VP of engineering, GM’s senior VP of global quality, Volvo Cars’ vehicle-safety chief, and Nissan North America’s recently retired senior VP of research & development. And there are more women serving as vehicle chief engineers, technology directors, and engineering managers than ever before.

But collectively they number less than one in five within the vehicle industry — at a time when acute competition and regulatory pressures are intensifying demand for fresh product development, technical, and research talent. Ford Motor Co., considered by professional-development experts to be one of the leaders (along with GM) in hiring and cultivating female engineers, currently has about 17% women in its engineering work-force, according to Felicia Fields, Group Vice President for Human Resources and Corporate Services.

“Our data over the last 10 years tells us that availability of female engineers has tracked at about 16% of the entire engineering pool, so we’re running slightly ahead of that,” Fields said. At GM, women engineers represent about 20% of the automaker’s U.S. engineering population and about 16% globally — its largest functional group of women employees, according to the company.

[OEMs closely guard their engineering-resource data, and no reliable independent metric exists to determine which one employs the most female engineers. Automotive Engineering sent formal requests to the world’s major automakers asking for their percentage of female engineers for this article; some offered a narrow snapshot such as their percentage growth over time. Others chose not to respond.]

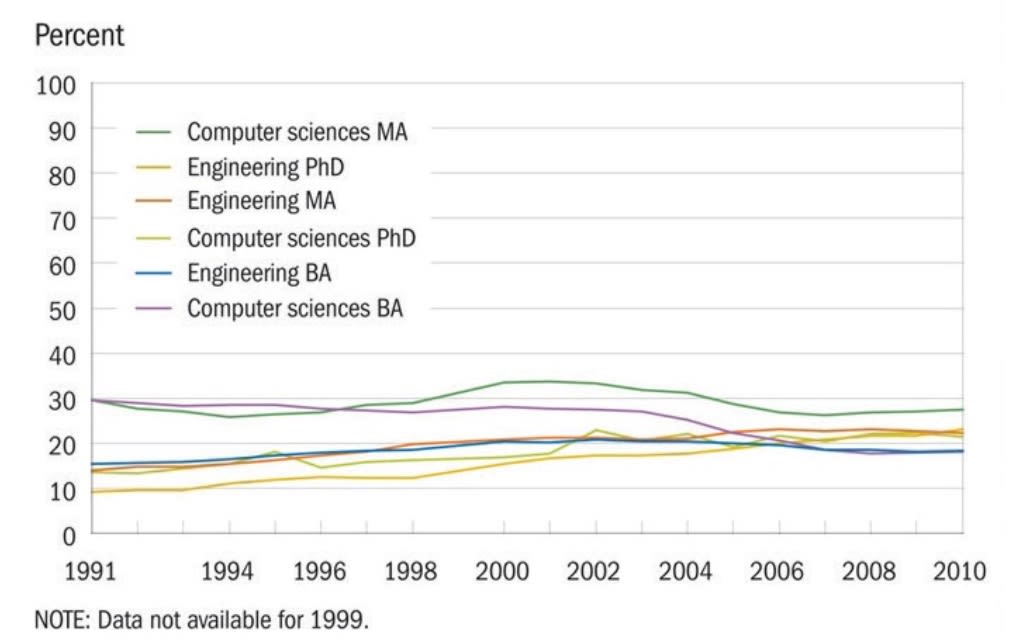

With the pipeline of available female engineers rich with talent, but trending flat since 2004, Caterpillar’s DelVecchio ponders, “With our successes thus far, why aren’t the numbers changing?” The answers are complex, varied, and indicate a critical need for the auto industry to do more to expand the pipeline and improve the work environment.

Narrowing the gap, slowly

Ongoing challenges continue to impede progress, say the more than two dozen human-resources experts, workforce researchers, and engineers interviewed for this article. First, they see the U.S. Detroit Three automakers and their North American suppliers as being in the vanguard of hiring and promoting female engineers since the 1970s, while their European and Asian counterparts (particularly the latter) have been outpaced due to various traditional cultural and societal factors, including a slower acceptance of women working outside the home.

“The work-life issue is why I think you’re seeing Europe and Asia lagging the U.S. industry,” observed Laura Sherbin, Executive Vice President and Director of Research at the Center for Talent Innovation (CTI), a New York-based non-profit think tank and co-author of a recent study on women in the science, engineering, and technology (SET) fields. “It’s because it’s institutionally accepted for women to be at home.” Women in Germany in particular, she noted, traditionally take long maternity leaves and have a difficult time getting back into the workforce. They are also more likely to interrupt their careers to care for others.

“It’s hard for them to have three jobs — parenthood, doing the housework, and having a professional career,” explained Dr. Heidelinde Holzer, the first female to hold a lead position (head of component integration) in BMW’s powertrain group. She added that “not as many women in Germany are entering vehicle engineering as we want, but they are coming.”

Government fiat is playing an active role in this trend. Since 2010 the European vehicle industry has heightened its efforts to hire and promote female engineers, among other positions, following the European Commission’s announcement that it would consider “targeted initiatives” — quotas — to boost gender diversity in corporate management. German automaker responses have varied. BMW, for example, established “target ranges” for gender across its workforce, with an eye toward increasing the role of women in leadership positions. Volkswagen’s Head of Powertrain Development, Dr. Heinz-Jakob Neusser, said his company has “programs supporting the female employees, but there is not a quota where we are regulating it.” Speaking with AE at the 2014 Geneva Motor Show, Neusser noted that “women represent 30-40% of engineering graduates from German universities, but there is not yet a clear trend in hiring. It’s in different areas — design engineering and also in the Electrical and Quality departments, not so much traditional mechanical engineering. When they are good, we take them.”

Asked if VW has academic programs like STEM curricula to steer girls and young women who excel in math and science into engineering, he said “We are working with the industry to find solutions.”

Japanese and Korean OEMs acknowledge they still have a long way to go in raising the number of women engineers working in their home-market facilities, even as the Japanese watched their country’s overall female employment rate rise to a record 62.5% in 2013, according to Goldman Sachs’ May 2014 “Womenomics 4.0” report. It’s actually quite rare for auto writers to encounter female engineers while reporting in those countries, but standouts are slowly emerging. An example of what HR leaders hope will be a typical career path is Chika Kako, who joined Toyota in 1989 as a materials engineer and soon began working in vehicle interior and exterior development. In 2001, she was posted to Toyota’s Europe R&D center, the company’s first female employee to work overseas in R&D. Recently, she became the first Lexus chief engineer, heading the CT200h hybrid program.

While traditions regarding gender roles have been an obstacle to building a balanced engineering and technical culture at home, the Japanese auto industry is pushing to narrow the gap across its North American operations. Nissan’s North American Technical Center in Michigan, for example, has increased its number of female engineers by 50% in the past decade. And its female engineering management — an extremely rare breed in Japan — has risen by 30% since 2009, the company claims. The good news is the Japanese auto industry is using its North American base to spearhead a wave of female-engineer gains in body engineering, interiors, electronics and software, safety-systems engineering, NVH and manufacturing engineering, and human-machine interface development.

One of many examples is Annie Boh, a graduate aerospace engineer working on vehicle aerodynamics and acoustics at Honda R&D Americas. Boh, a 12-year Honda veteran, oversees the critical task of minimizing wind-noise sources on the vehicle exterior during new product development, spending many hours in the wind tunnel and with analysis tools. The major companies also are engaging U.S. and Canadian universities, and elementary and secondary schools to help grow their personnel pipelines.

Workplace climate a key to retention

The issue of retention is serious for women in SET professions globally. In 2008, a CTI Athena study showed that women were dropping out of the SET fields including automotive engineering despite a robust talent pipeline. Over time, 52% of highly qualified women working for SET companies quit their jobs for a variety of reasons including hostile work environments, isolation, and a lack of clarity regarding career paths, according to the study.

Last February, CTI published a follow-up to the 2008 study, expanded to include Brazil, China, and India. It focused on identifying positive changes SET women had experienced since the 2008 report and offered solutions for what had resisted change. The new study, called Athena 2.0, found plenty of promise in the past five years. Women have become the majority of SET college graduates in key global regions (51% in North America, 46% in Europe and the Middle East, and 30% in Asia). An overwhelming majority of SET women are dedicated to their professions and love their work.

But the research found that significant numbers also said they feel “stalled” in their careers — and are likely to quit their jobs within a year (i.e., 32% in the U.S., 20% in India). Their stated reasons aren’t much different from those that Cindy Hess faced in the 1980s, though not as overt. They included unspoken male-biased workplace cultures that present potential roadblocks for women to get their ideas across and impede their paths to leadership roles. There is also a lack of female professional networks within organizations, the study found.

In the U.S., decades of involvement by government, industry, and academia to help open the traditional “boy’s club” and narrow the gender gap leaves female engineering leaders frustrated with the slow pace of progress. Women comprise more than 20% of engineering school graduates, according to a compelling 2011 University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee study, yet only 11% of practicing engineers are women. A related project aimed at understanding factors related to women engineers’ career decisions surveyed over 5500 female engineering graduates. Twenty percent of those surveyed found workplace climate, rather than family reasons (8%), to be a significant factor in their decisions to leave the profession, or simply not to enter it after graduation. Conversely, workplace climate also was cited as being a factor in current engineers’ job satisfaction and intention to remain in engineering.

According to Dr. Nadya Fouad, one of the study’s authors, one-third of the women surveyed who did not pursue engineering after graduating said it was because they perceived the field as being inflexible, or the culture as being nonsupportive of women. Other recent research, including a 2011 report by the American Association of University Women, noted other factors including few female mentors and faculty along the education pathway, and even wildly erroneous stereotypes that women aren’t as capable in the STEM disciplines as men.

Salary also can be a factor in both attracting and retaining new engineers, and females in the mobility-engineering field face an average salary deficit of between 8% and 12% compared with their male counterparts (across the automotive, off-highway, and aerospace sectors), according to the 2014 SAE Mobility Engineering Salary Survey.

Snarling with the ‘alpha dogs’

A recent quote from a female Stanford University engineering graduate brought back memories to Denise Gray, the Vice President of Powertrain Electrification at global engineering consultancy AVL List.

“Just walking into the classroom is one of the biggest hurdles for women entering this [engineering] field,” the Stanford grad recalled. “You go in and you’re the only girl in there.” The image evoked Gray’s long-ago experience at Detroit’s famous Cass Technical High School, “where it was only me and one other girl” in Cass’s specialized pre-engineering curriculum, which led Gray to an E/E degree at Kettering University and a master’s at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Gray, who is building a network for female engineers within AVL, also laughs when she recalls her experience among the all-star team of primarily male, often high-strung engineers who held core positions in GM’s original Chevrolet Volt program, while Gray was GM’s Global Director of Energy Storage Systems. “Those guys were sometimes called ‘alpha dogs’ by one of my female former colleagues,” Gray noted. “But neither of us were deterred by that environment. My mantra was always to do a really good job, and prove that you’re working hard for the sake of the whole team. When you do that, eventually those ‘alpha dogs’ will come around and accept you.”

It’s all about having the right attitude. And being few among many can have advantages, according to Beth Ardisana, CEO of ASG Renaissance, whose services include executive talent searching, talent management, and staffing. A former Ford vehicle development manager, the scrappy Ardisana entered the auto industry in the 1970s (“my brother was insanely jealous”) with a mathematics degree and years of experience building and racing cars and hydroplanes. She eventually served on the President’s Task Force for Implementation of Alternative Fuel Vehicles and the Natural Gas Vehicle Coalition board.

“I had an exciting job in a great company. There were some hard parts to it, no doubt, but there wasn’t a moment during my time there when I didn’t think I was getting a fair deal because I was a woman. What I found was you have to distinguish yourself,” she said.

At a time when management “were all men wearing the same blue suit, I was a woman. Of course, more visibility can be a double-edged sword — every mistake you make is elevated,” Ardisana said. “But I had more opportunity for no other reason than because I was different.”

She is optimistic that the flat line that has represented the number of women in engineering will eventually turn north, “because in this current era there’s a huge group coming up. So there’ll be more and more of us.” But Ardisana sees a bigger challenge that goes beyond just attracting women to the auto industry. That is, the industry needs to attract engineers, period.

The first matter is how to increase the number of people in STEM education and the number of graduating engineers. Then the auto industry needs a major, perpetual campaign to make engineering look more attractive, interesting, and fun. “Women have to see how engineering impacts what they care about,” noted Ardisana. She admitted that the new era of vehicle electrification has attracted engineers, chemists, and scientists, but not in the numbers she once envisioned. “We have good-paying, interesting jobs, but it’s important that people think what we do is important,” she said.

“There’s really nothing in the public eye that shows what engineers do and why we’re so vital,” observed Sue Cischke, the veteran Chrysler and Ford engineering executive whose promotion to Group Vice President of Sustainability, Environment, and Safety Engineering was among the first top-level promotions Ford CEO Alan Mulally made upon his arrival at the automaker in 2006.

While a board member of the University of Michigan College of Engineering Advisory Council, Cischke often struggled with why female engineer graduation rates hovered at 12-15%. “I still wonder why this is happening,” Cischke told AE, “but I think the real issue is women who are strong in math and science tend to see medicine or law as more appropriate professional roles. They don’t view the auto industry as ‘high tech,’ yet we’re more high-tech than many of the quote-high-tech sectors.”

Engaging more girls and young women with STEM programs will help grow the available “pool” of female engineers. Even small improvements to a workplace culture can have positive effects on the recruitment and retention of all employees, not just women. Such changes in the future could help make Felicia Fields’ short-term goal — having at least 20% women across Ford’s (and perhaps the industry’s) engineering groups — a reality within 10 years.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...