Inside the Bolt EV

While the new battery deserves credit for the car’s +200-mile range, systems optimization, careful motor design and proprietary CAE tools were equally important.

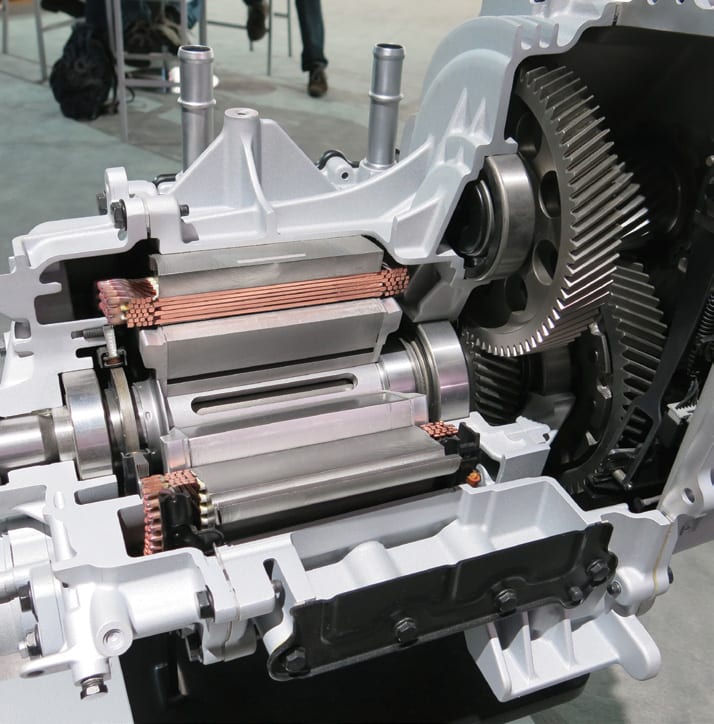

Cutaway propulsion systems displayed at motor shows attract engineers faster than free beer and pizza. So perhaps it wasn’t surprising when Matthias Mueller, the newly-promoted chairman of Volkswagen Group, and his five-man entourage charged into the Chevrolet stand during the 2016 Detroit auto show.

“Hier ist es,” (here it is) said Mueller’s assistant, pointing to the 2017 Bolt EV propulsion module unveiled earlier that day. The dark-suited VW execs huddled closely around the cutaway property, its traction motor and large helical gearset in full view through the artfully milled aluminum case. One of Mueller’s lieutenants — who may have studied the Chevy module already — listed some design high-lights while Mueller listened attentively. A fellow carrying a notepad made a technical sketch while another snapped close-up photos.

Within ten minutes they departed. The author and Steve Poulos, GM’s veteran chief engineer of electric-propulsion systems, stepped back to the cutaway. We picked up our own discussion from before the interlopers arrived.

“That’s not the first competitor to visit us today,” Poulos noted. “We knew we’d get some interest.” Such understatements from the engineering team a year ago foreshadowed numerous awards to come for the newly-minted Bolt EV, including 2017 North American Car of the Year. As the first production battery-electric vehicle to deliver more than 200 mi (322 km) range at a price less than $40,000, the Bolt EV proves the strategic collaboration between GM Global Propulsion and LG Electronics Vehicle Components is an EV development force. The LG Corp. group was established in 2014 to co-develop the Bolt powertrain and other subsystems. Much of their triumph has been credited to the Bolt’s

battery pack, featuring a new nickel-rich Li-ion NMC chemistry which gives greater heat tolerance without impacting battery life, according to Bill Wallace, GM’s director of global battery systems. Larger cells with more surface area deliver a 40-kW gain over the previous Spark EV pack. Nominal energy is increased more than 3X, from 18.4 kW·h on Spark EV to more than 60 kW·h for Bolt, with only a doubling of battery mass.

It’s a significant increase in both gravimetric (Watt-hours/kg) and volumetric (kilowatts/L) energy (see table). Its high thermal mass — the pack weighs 959 lb/435 kg — means temperature swing during operation is single-digit minimal. There isn’t much wasted heat, which helps improve the amount of energy recuperated during the Bolt EV’s “single-pedal” lift-off deceleration and regen braking. Automotive Engineering editors call it “the small-block V8 of battery packs.”

Motor design details

But systems optimization of the battery, e-motor, gearing power control and thermal management is the bigger story behind Bolt EV, Poulos noted.

“We looked at numerous ways to optimize the motor to achieve peak [97%] efficiency,” he said, “because the more efficient we make the motor, the less battery we need to carry to achieve our 200-miles range.” Designed in-house at GM, the motor program found the ideal magnet location in the rotor to break up frequencies and squeeze out as much torque density as possible.

The neodymium iron boron (NdFeB, or NIB) magnets are placed deep within the rotor in a two layer ‘V’ arrangement, assymetrically between adjacent poles to minimize torque ripple and radial force. A double-layer arrangement of magnets and barriers offers design flexibility and boosts motor performance at higher speed. The bar-wound stator construction is a GM e-motor trademark that provides high slot-fill, improved thermal performance and higher efficiency, the engineers said.

Poulos’s team also realized the permanent-magnet motor needed to spin significantly faster than that of the Spark EV to produce the power needed for the larger, heavier Bolt and its much-higher performance targets. The new motor’s 8,810 rpm peak is nearly twice as high as that of the Spark motor. It runs on slightly lower current for more efficiency. Peak torque is less than the Spark motor but axle torque is higher due to a higher (7.05:1 vs. 3.87) final drive ratio.

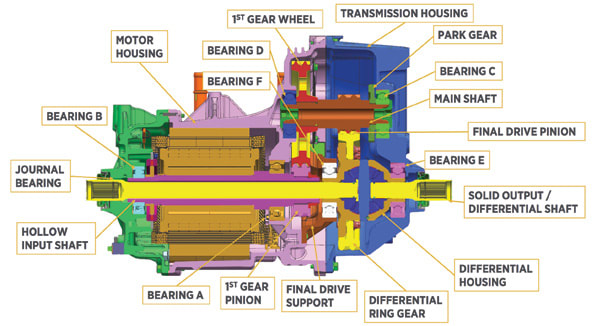

That helped reduce the propulsion unit’s weight (167 lb/76 kg, most of which is the 150-kW motor) and package volume. The drive unit’s compact design allowed it to be located precisely in the vehicle centerline, which enabled identical-length axle shafts. The result was minimized torque steer, reduced integration cost and greater manufacturing efficiency.

Additionally, the single-speed gear-set architecture created advantages in the park system loading. Also, the split lines between the end cover and motor housing and between the motor and gearbox housings increase structural rigidity. This in turn enables the motor assembly to be manufactured as a separate stand-alone unit and allows motor-compartment maintenance without disassembling the entire drive unit.

GM’s unique analysis tool

The lubrication system in this electronic-automatic propulsion device is a combination of pressurized and gravity feed/flow. It uses a 12-V variable speed pump mounted outside of the transmission housing. The low-pressure pump will only run when out of Park or Neutral and vehicle speed is detected. The 12-V pump also helped optimize filter position and minimized ATF volume inside the drive unit, which helped reduce cost, mass and drag/spin losses, Poulos noted.

Key to the propulsion system meeting and in some ways exceeding its design targets was a proprietary CAE program, said Poulos. “We input all the different maneuvers we want to design this motor to do — various drive cycles, climbing a grade, 0-60-mph acceleration, passing maneuvers, etc. — to generate thousands of points on the torque-speed map.”

Without the unique analysis tool, the thousands of combinations would require far more time to sort out. The program then breaks the map into zones and prioritizes them according to their importance to the car’s performance. It then generates a ‘center of gravity’ for each representative point.

“Then we do a Design of Experiments and a whole series of design variables and it gives us the optimum,” explained Poulos, who is now chief engineer of GM’s fuel cell activity. “We keep adding these points until the data converges into an answer that doesn’t change.”

Added Tim Grewe, GM director of general electrification, “It’s a very powerful technique we developed internally to ensure we have no more iron, copper, size and mass than we need to meet our performance requirements.

“From a customer-pleasing point of view, this program goes way beyond the cycle, which we also weighed into the calculation to determine what to optimize,” Grewe said. “It tells us quite precisely that we’ve optimized the motor for every drive cycle without compromising something that disappoints the customer.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...