Achates Powers toward Production

A potential ICE game-changer, the Achates OP engine is being tooled up for production at one OEM while a new 2.7-L triple for light-truck demonstrations enters the build phase.

Nothing short of a game-changing technology has any chance of disrupting the world’s combustion-engine mainstream, it is generally believed. Felix Wankel’s rotary came the closest, carving out a successful niche at Mazda after GM spent millions tooling up for, then killing, its own high-volume rotary program in the 1970s. Now comes Achates Power, the San Diego technology company that has brought its opposed-piston, 2-stroke, compression-ignition engine to the brink of production after 13 years of careful and relentless development.

At January’s 2017 Detroit auto show, Achates’ top engineers made two promising announcements. First, one of the company’s nine global OEM customers has begun tooling an engine plant for serial production of an Achates ‘OP’ engine. While no details or timing were provided, Achates’ current customer base includes applications for passenger-vehicle, light and heavy commercial vehicle, military and marine/stationary power. The engine programs span a broad range of fuel strategies and configurations — from 50-hp (37 kW) single-cylinder units to 5000-hp (3768-kW) twelve-cylinder monsters aimed at stationary and marine use. Development also includes a gasoline compression-ignition program (see sidebar).

Achates CEO David Johnson also reported that a new 2.7-L 3-cylinder diesel unit — each OP engine has two pistons and con rods per cylinder, driving two geared crankshafts — is entering the build phase. A batch of engines will then start clocking dyno time in preparation for light-truck on-road demonstrations and customer evaluations in 2018. Turbocharged and supercharged, the 2.7-L will be capable of delivering 270 hp (201 kW) and 479 lb·ft (650 N·m) at crankshaft speeds comparable to current-production light-duty diesel engines, he said.

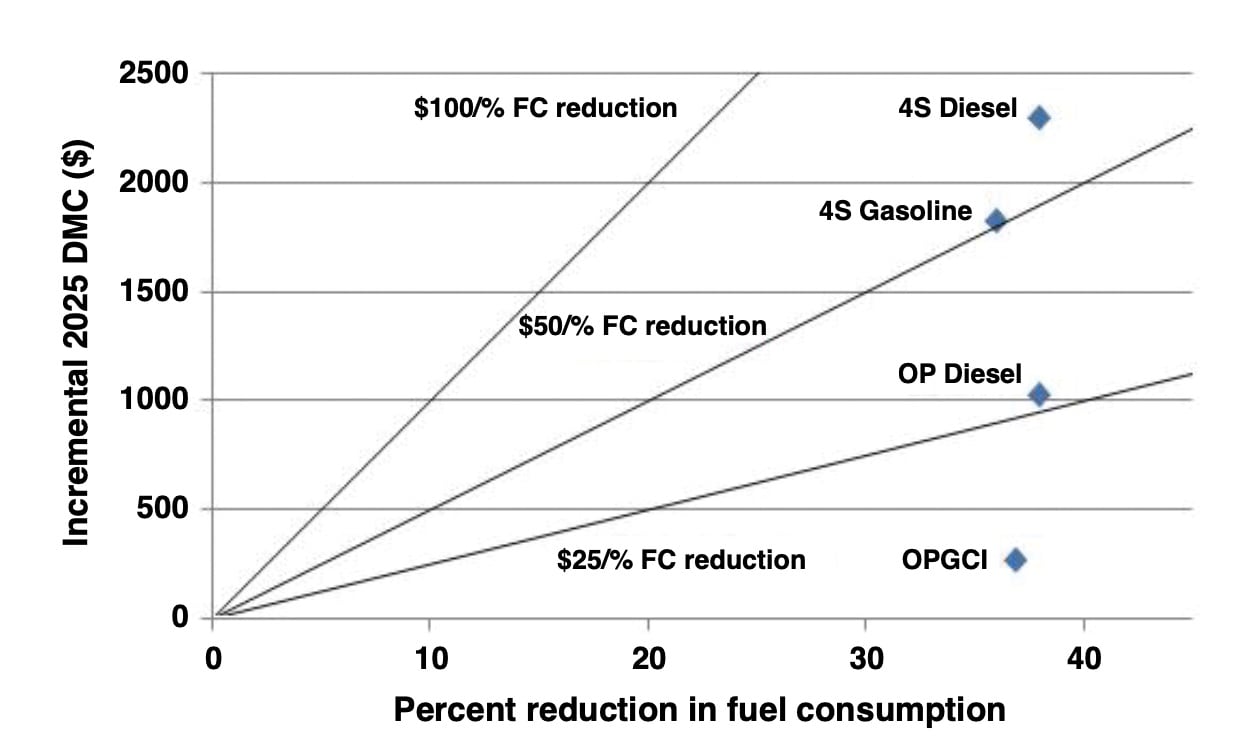

The demo units, their fully-dressed package volume and mass equivalent to that of Ford’s 2.7-L Ecoboost V6, will be installed in full-size pickups and/or SUVs — the market segment Achates is promoting for its volume, profit and CAFE-impacting potential, Johnson explained. The 2.7-L “will be fully measured and characterized and will achieve 50% improvement in fuel economy versus downsized, turbocharged, spark-ignited gasoline engines today.” It will also be 30% more efficient than the best incumbent passenger-vehicle diesels, he said.

Johnson quoted a 37-mpg (unadjusted) CAFE number for the engine; 2025 U.S. regulations call for vehicles with a 65-70-ft2 ‘footprint’ to deliver 33 mpg. City/highway/combined EPA fuel economy for an Achates-powered base truck calculates at 25/32/28 mpg.

“We’ll have a ‘CAFE-positive’ vehicle,” he asserted. Johnson, a veteran of GM’s global diesel engineering and Ford truck product planning before joining Achates Power in 2008, also is confident the 2.7-L six-piston OP diesel will meet the federal Tier3 GHG fleet average of 0.03 g/mile NMOG + NOx with minimal tradeoffs in BSFC. Upcoming Euro6 standards also are achievable he said.

Development work conducted with Johnson Mathey, Emitec and other aftertreatment-system suppliers project the OP engine’s aftertreatment-cost burden to be 30% less than current-production light-duty diesels, according to Johnson. Smaller catalysts (with less precious-metal content) are required due to the OP’s comparatively low engine-out NOx emissions.

Particulate formation is inherently reduced due to the OP’s injection environment, the engineers claim. Two injectors per cylinder, fed by a 2000-bar common rail, spray fuel across the cylinder bore perpendicular to piston travel towards top-dead center. Fuel droplets therefore “do not impinge on the combustion chamber wall, dramatically reducing soot formation. As we run, test and measure our engine, we find its soot production to be low. We have tremendous datasets [regarding PM] with our diesel,” Johnson explained. He expects, though, that Achates’ gas and diesel engines will at some point require PM filters.

Traditional 4-stroke gasoline ICEs are least efficient during low-speed/low-load operation — the region where most drivers spend most of their time. Rondon noted that Achates’ OP engine has demonstrated its ability to minimize the efficiency drop at low loads; where traditional 4-strokes’ pumping comes from their systematic “suck-spark-bang-wheeze” cycling, the OP’s supercharger, currently an Eaton unit, provides independent cylinder charging. It can be adjusted to supply precisely the amount of air needed per quantity of fuel injected, providing what Rondon calls an advantage over the incumbents in low-load/low-speed running.

The operating characteristics, inherently good primary balance and steady-state emissions profile also lend themselves to hybrid applications; Johnson noted that Achates has a study underway for a small-displacement (600cc-700cc per cylinder) range extender.

“Our opposed-piston engines are the most cost-effective, fuel-flexible, power-and-torque-dense solution for OEMs to meet the CO2 and fuel economy regulations of the next decade, without having to change the world’s fuel infrastructure,” Johnson told Automotive Engineering in December 2016 during a visit to his company’s headquarters.

$1000/unit cost savings

The industry’s expanding interest in Achates Power OP developments includes work with Cummins on the U.S. Army TARDEC Advanced Combat Engine, a single-cylinder demonstator, plus programs with Fairbanks-Morse and the ARPA-e OPGCI project with Delphi and Argonne noted in the sidebar.

The engineering team’s enthusiasm continues to grow with each week of testing and development. “There was a time when I joined Achates Power that I didn’t know if the technology would work or not,” Johnson admitted. “Now, I have absolutely no doubt we’ll get into volume production. When we started, top powertrain engineers from major engine companies said to me, ‘You’ll never be able to achieve good combustion with this engine.’ So we went to work on that. We solved that problem and patented the solutions and demonstrated them. We did the same with NVH.” Achates currently owns 120 patents on the OP engine with another 200 pending.

Company founder Dr. James Lemke saw significant advantages in the basic OP 2-stroke design that has powered aircraft, ships and military vehicles since the 1930s. He believed that clean-sheet re-engineering and application of the latest technologies could boost the OP’s historic attributes — low heat rejection, high expansion ratio, lean combustion and reduced pumping losses — and reinvigorate the engine for 21st century propulsion duty.

For background, see SAE Technical Paper, “An Analytical Assessment of the CO 2 Emissions Benefit of Two-Stroke Diesel Engines,” Alok Warey GM R&D, et al, http://papers.sae.org/2016-01-0659 .

Many factors contribute to Achates’ claimed $1000 to $1500 per-unit cost savings for its OP engines versus comparable current LD gas and diesel engines, explained Fabien Redon, Vice President, Technology Development. Bill-of-material advantages are significant because there are no cylinder heads, gaskets, camshafts or valvetrain. Along with head machining, the head(s) and valvetrain typically account for 15-20% of the cost of a 4-stroke base engine. This more than offsets cost of the OP’s second crankshaft and supercharger, Redon said.

Compared with a state-of-the-art V6 with supercharger, the 2.7-L Achates OP’s BoM is more than 60% smaller, enabling an approximate 10% cost reduction, he noted.

Engine assembly is simplified and there is minimal “all new” in the manufacturing process, the majority of which is shared with incumbent ICE production. The Achates’ long stroke-to-bore ratio (typically 2.2:1) helps deliver strong output-torque characteristics that may lessen the need for 10-speed transmissions now emerging in the industry.

“Our fuel maps for both the gas and diesel engines are similar — and they’re much flatter than those of other light-duty diesels, so we don’t need all those [transmission] speeds,” Johnson surmises.

And without a cylinder head, the OP rejects less heat to the coolant. The resulting lower radiator and fan loads mean those components can be reduced in size. A powertrain-engineering expert contacted by the author for comment, who is familiar with Achates’ technology called the 2.7-L project “quite viable in virtually every metric to this stage.”

Oil consumption no issue

Like countless classic piston-port 2-stroke motorcycle engines, the Achates OP has its intake and exhaust ports in the cylinder walls — but with the intakes at one end of the cylinder and exhausts at the other. The ports are opened and closed by the piston motion, enabling “uni-flow” air scavenging. But the piston-port design also was the Achilles’ heel of those historic engines, contributing to excessive oil consumption as the piston/ring assembly drags the oil film past a port with every piston reciprocation. The term “oily mess” was probably coined by the black-coated Detroit Diesel 6-71 engines that powered every GM city bus.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...