Supersonic Spy Drone

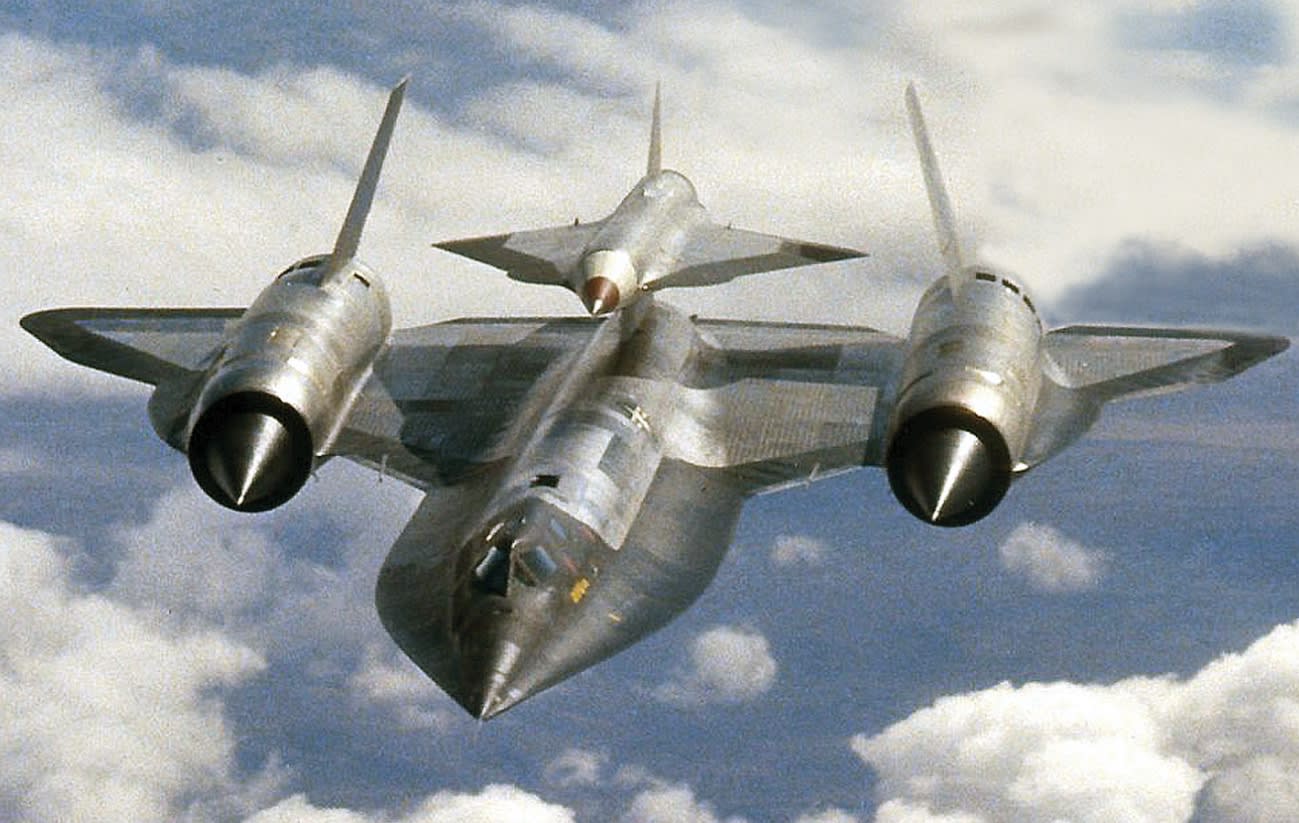

To light off its ramjet engine, the 2,300-mph D-21 needed a blindingly-fast launch platform. Enter the Lockheed A-12.

When is that wild thing coming out? It would be a reasonable question for an average reader to ask after looking at a picture of the futuristic D-21 drone, a windowless aircraft with a sharp cone-shaped nose, a delta-shaped wing-fuselage structure and a single vertical tailfin. Code-named ‘Tagboard’ during its CIA- and Air Force-funded mid-1960s development by Lockheed’s secretive Skunk Works advanced-projects group in Burbank, Calif., the D-21 was intended to answer a question that was driving U.S. national security officials mad: How was the Chinese military progressing in its effort to build and test nuclear weapons?

Flying a spy plane over China’s remote testing facility at Lop Nor was considered far too risky after a camera-equipped U-2 spy plane piloted by Francis Gary Powers was shot down on a mission over the Soviet Union in 1960. Thus, momentum quickly built for the idea of building a much faster, high-flying aircraft with no crew onboard at risk of capture or death. The U-2’s subsonic speed made it too vulnerable to increasingly lethal surface-to-air antiaircraft missiles.

The new spy aircraft would have to be capable of flying at speeds of Mach 3.3—or around 2,300 mph; Lockheed’s engineers drafted plans for what became the D-21. Its powerplant was a mechanically simple ramjet engine built from special high-temperature alloys by Marquardt Corp., then located in Van Nuys, Calif. A limitation of high-speed ramjets is that they must be accelerated to well past the speed of sound before combustion can be established and exhaust ejected through a divergent nozzle at the back of the engine, creating thrust. The pointy nose managed supersonic shock waves to keep airflow orderly on its way to the engine’s inlet duct.

How to get the D-21 up to the speed of sound: the A-12 Oxcart, a Mach 3.2 Lockheed spyplane that was an early version of the celebrated SR-71 Blackbird then well along in its development.

Mounted atop the Oxcart, the D-21 could be fired up and sent on a programmed route to the desired imaging target. The drone’s payload was contained in a belly-mounted ejectable pallet stuffed with a high-resolution camera, film, an inertial guidance system, self-destruct and communication equipment, a parachute and other necessities.

Modified with a pylon supporting the drone between its twin tails, the aircraft was referred to as the M-21, with the letter M signifying “mother,” as in mother ship. Three successful test flights were conducted over the Pacific Ocean off Point Mugu on the California coast. The M/D-21 combination took off from the secret Area 51 test base at Groom Lake in the Nevada desert.

On the fourth test flight in 1966, with Lockheed test pilot Bill Park at the M-21’s controls and Ray Torick in the rear seat serving as launch-system operator, the D-21’s ramjet started up and the drone began lifting off from the mothership’s back. Then the drone rolled to the right, smashing one of the M-21’s tailfins and causing the plane to pitch up sharply and break into two pieces. Park pushed the aircraft’s control stick full forward to bring the nose back down, with no result.

It was then that he realized there was no more airplane remaining aft of the cockpit.

“I always said that as long as things inside the aircraft were better than they were outside it, we should stay inside,” said the late Mr. Park in an interview several years ago. “I quickly decided that things inside were rapidly getting worse and it was time for us to eject.”

Both crewmen parachuted to a splashdown in the ocean, where Park was rescued, but Torick’s flight suit filled with water and he drowned. Torick’s death caused Lockheed to abandon the hair-raising drone-launching method and two B-52 bombers were outfitted to carry a pair of drones under their wings. A rocket booster was fashioned to get the drones up to launch speed where their ramjets would ignite. Four operational missions — with mixed results — were completed in this fashion before the remaining ramjet drones were retired and given to museums or stored at the famous “boneyard” at Davis Monthan Air Force Base outside Tucson.

The audacious supersonic drone program, with its hot-rod ramjet, was so far out on the bleeding edge of the possible that it outpaced any existing technology to support it.

Stuart F. Brown is an award-winning technology writer based in Albuquerque, New Mexico, specializing in aviation, advanced manufacturing, transportation and science.

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance