Clearing the Air on 2025 GDI Engines

Tim Johnson, Sc.D., a global expert on vehicular emissions technologies at Corning, previews the next round of emissions control regulation that includes particle filters for gasoline units.

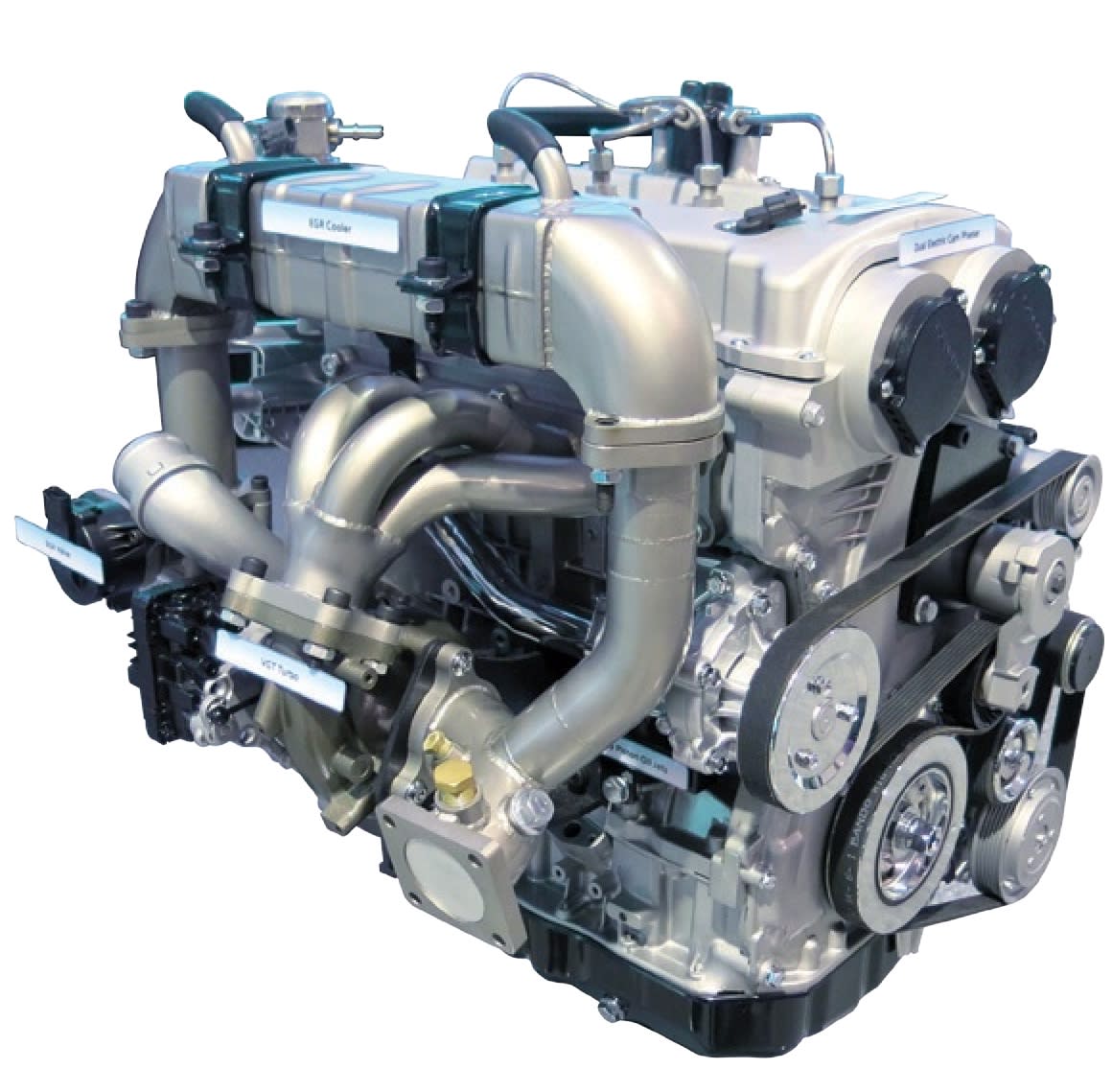

Powertrain engineers who attended this year’s SAE International High-Efficiency Engine Symposium and World Congress heard one message loud and clear: Don’t bet against the internal combustion engine. In particular, the gasoline ICE continues to bob, weave, and counterpunch against heavy regulatory actions that some feared would knock it out of the ring.

Technical innovation is not only keeping the gas engine alive, but also improving and evolving it as the benchmark power source for light-duty vehicles. Recently we discussed its status and likely future with Timothy Johnson, Director – Emerging Regulations and Technologies for Corning Environmental Technologies, part of Corning Inc. An SAE Fellow and prolific contributor to the industry’s technical literature, Johnson is one of the most insightful experts in his field. Excerpts from our conversation follow.

With all the upswing in activity in combustion-engine development, there’s clearly much promise for the gasoline ICE. Are you surprised at the pace of R&D?

I agree. I think the industry’s getting less risk-averse, and you could see that in a lot of the advanced-combustion presentations at this year’s SAE Congress. You don’t have a small ‘sweet spot’ [range of optimized operation] on the engine map anymore. That ‘sweet spot’ is enlarging. Look at the various dedicated EGR approaches, such as what Achates Power was showing in diesel. And Mark Sellnau (Engineering Manager of Advanced Powertrain Technology at Delphi Powertrain) was showing a large and potentially growing sweet spot on the engine map for the Delphi-Hyundai GDCI (gasoline direct-injection compresssion-ignition) engine.

You don’t need a hybrid to operate more in that zone, although hybridization is another benefit for the ICE. You can extract much of the benefits of running in the ‘sweet spot’ with an 8- to 10-speed transmission.

As we move toward lean combustion strategies, what are the drivers behind particle filters for GDI engines?

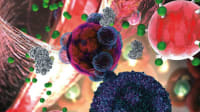

Information continues to emerge on the health effects of even gasoline engines, and there’s a trend worldwide looking at particle matter. Preliminary evidence shows that ultrafine particles are more hazardous than the intermediate-size ones. If you look at the PM2.5 fraction (particle size less than 2.5 micron), the PM0.1 (to pick an ultrafine fraction) likely represents the majority of the health effects of the whole PM2.5 fraction.

In the U.S. we need strong health monetary benefit on a tailpipe regulatory level, but not on the NAAQS (National Ambient Air Quality Standards) levels which guide everything. But when you start regulating industry, benefit/cost ratios are needed for that regulation. And to get those ratios we need epidemiology studies. We need to know mortality rates as a function of the pollution level, and have enough of those studies so we can statistically derive a benefit of reducing that pollutant.

Are those studies going on now?

They are, and the Health Effects Institute ruled about a year ago that there isn’t enough epidemiology data on particle number, or ultrafines in general, to promulgate a regulation on industry. They believe the PM2.5 regulation, for the time being, captures the toxicity of ultrafine particles. Now in Europe, they’re not held to this standard or level of requirement. European regulators have enough latitude that directionally, if they see health effects or issues, they can be proactive and implement the regulation.

In the toxicology — the biological studies where you take a look at exposure to animals and to humans; in many cases, you do cell biology studies — the toxicity of particle number, of very fine particles, is very well established. You can clearly see how these particles penetrate the blood/ air membrane. The studies are becoming quite convincing that there is an effect — but this hasn’t yet transcended into the epidemiology.

New advanced-combustion engines will have future implications in this area?

Sure. What causes the particle number in the cylinder are stratified charges, where there is a high concentration of fuel relative to the air. You end up with remnants that aren’t fully burned and the remnants can form solid carbon-based particles. So in any stratified charge you have the risk of a high particle-number emission, even though the particle mass might be very low.

For years the discussion was on particle mass. Then particle number (PN) was introduced as a regulatory metric.

Yes. It all started in Europe because of the toxicology. PN is a more reliable metric for low particulate levels, as you can have a lot of these very fine particles but they have very low mass.

[Editor’s note: A tighter particulate-matter mass measurement was introduced with the Euro 5/6 legislation. In addition to the 0.005 g/km mass-based limits, the law also introduces a 6.0 x 1011 particles/km emission limit for spark-ignited vehicles, which is identical to the diesel limit and applies from the start of Euro 6c on Sept. 1, 2017. Until then, manufacturers can choose to certify to a limit of 6 x 1012 particles/km. The European Commission recognizes the current drive cycle does not capture all operating conditions, so it is working to establish a real-driving emissions (RDE) test procedure for PN testing.]

How is this impacting future GDI engine aftertreatment technology?

Well, GDI engines are an effective way of meeting the CO2 and market requirements. However, they inherently have much higher PN emissions.

Depending on engine architecture and approaches, the PN limit can be met in certification and dynamometer testing but cost is a consideration. A gasoline particulate filter (GPF) is a robust and cost-effective solution. However, the new RDE regulation in Europe will drive additional emissions needs. The European Commission is requiring all RDE PN solutions to be as robust as the filter. Approach will depend on how tight the RDE regulation will be. We are now seeing, and will see, much more GPF applications to meet these needs.

[Editor’s note: Mercedes-Benz’ new lean-burn 2.0-L four-cylinder gasoline engine is a bold move in this technology area. Currently available in the E250 Coupe and CLA 250, it is a member of Mercedes’ BlueDIRECT family of gasoline engines that will power A-, B-, and C-Class models. The engine features external high-pressure EGR and operates in homogeneous or lean-burn stratified modes, depending on operating conditions.

Looking out to 2025, what’s your view of what the typical GDI light vehicle will have in terms of exhaust aftertreatment —and the cost in that technology suite?

In the U.S. we’re talking about a regulation that’s 80% tighter than today’s. This Tier 3 regulation is roughly an order-of-magnitude tighter than Euro6. So if we can maintain cost in the emission control system that may be a very aggressive target for us to hit. I would anticipate small-increment cost increases to meet a LEV 3 or U.S. EPA Tier 3 target on GDI engines, vs. Tier 2. I’d estimate they’re probably low double-digit increases in cost. But if I were to put on my logic hat and look at history, I think costs have a good chance of being maintained.

We’ll have different approaches — different catalyst systems, substrates, engine management strategies, and so on. One guiding element is the EPA Tier 3 cost projections. They are looking at nominally $70-$100 per vehicle. But the EPA is notorious for overestimating cost projections.

As the engineers get on it and start optimizing, and we get the entire industry moving in that direction with calibration and catalyst formulations, I see that as a ceiling on which we can improve quite significantly.

The U.S. regulation we have today will likely not force particle filters on GDI engines. The 2025 time frame in California could do it, but that’s 11 years from now. A lot can happen in that time frame. We are going to see GPFs in Europe in the 2017 time frame. But whether or not those filters will be on U.S.-market cars when they’re imported from Europe remains to be seen.

What emerging engine trends are you watching?

I think we will see more lean-burn gasoline engines, as the incremental cost of CO2 reductions relative to stoichiometric GDI engines could be very attractive. Most of the cost will be in lean-NOx reduction, especially in the U.S.

I always bet on technology.

Me too! You’re going to lose if you bet against it.

Transcript

No transcript is available for this video.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsAutomotive

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

ArticlesAR/AI

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

Road ReadyDesign

Webcasts

Semiconductors & ICs

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Power

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

AR/AI

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility