GM Puts Its New Z06 Corvette V8 on a Different Plane

GM Propulsion hasn’t forgotten how to engineer compelling ICEs, and is readying an all-new, high-performance V8 with a race-proven flat-plane crankshaft.

Cadillac didn’t invent the V8 engine, but GM’s premium brand deserves credit for advancing that prime mover’s cause over the past century. One of the most significant strides came in 1923 in response to GM Research Laboratories head Charles ‘Boss’ Kettering’s challenge to his engineers: Rid Cadillac V8s of their inherent roughness. The result was Cadillac’s 90-hp Type V-63 V8 built with crankshaft connecting-rod journals spaced at 90 degrees instead of the more-conventional 180-degree intervals.

Although every V8 maker quickly followed suit to achieve similar gains in smoothness, that hasn’t discouraged a few OEMs – including GM – from reconsidering 180-degree cranks. The recently announced 2023 Chevrolet Corvette Z06 is the newest wave in this technological tide, with a teaser audio clip already available.

According to a highly-placed GM Propulsion source, the company’s V8 past is back. An all-new DOHC V8 earmarked for the upcoming Corvette Z06 will be equipped with a flat-plane crank to assure that the intake and exhaust events in each cylinder bank are spread 180 degrees apart. Expectations are that GM will shorten the current 6.2-L LT2 V8’s stroke to create a more powerful – and more exotically vocal – 5.5-L V8, internally coded LT6.

What’s old is new again

In 1921, GM mathematician Roland Hutchinson designed what he called a ‘quartered’ crankshaft at the company’s Dayton, Ohio, research lab. All production V8s at the time used flat, single-plane cranks that were the logical extension of four-cylinder practice. These cranks had four throws – each carrying a pair of connecting rods – lying in one plane. Such designs minimized both material and machining requirements.

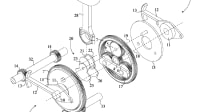

Hutchinson was inspired by Archibald Sharp’s 1907 ‘Balancing of Engines’ reference book and subsequent technical papers. To visualize the alternative 90-degree – or cross-plane – design, imagine a compass attached to the end of the crankshaft. A flat-plane crank has two throws at the north position and two aimed south. The cross-plane design has one throw every 90 degrees at north, east, south, and west positions. Both designs attach two connecting rods to each throw and their blocks have 90 degrees between cylinder banks.

The ‘rough period’ Kettering called out was vibration at a frequency equivalent to twice crankshaft speed – second-order vibration. Despite Cadillac’s practice of carefully weighing and balancing pistons and connecting rods and counterweighting its crankshafts, the shakes common to four-cylinder engines persisted when the cylinder count was doubled in a flat-plane-crank V8. The only difference was that the vibration shifted from the vertical to the horizontal plane.

Hutchinson’s ‘quartered’ crank realigned unbalanced piston motions in such a way that shaking forces were completely cancelled. As a result, cross-plane-crank V8s have enjoyed broad acclaim over the last century of use.

Flat plane benefits

What’s inspiring some automakers to reconsider use of flat-plane-cranks are the compelling advantages exclusive to such designs. They’re notably lighter and have less rotational inertia. Surrounding crankcases can be lighter and smaller. Racing-engine designers appreciate every cubic centimeter of volume saved, every gram of weight trimmed, and a flat-plane crank’s inherent ability to spin more rapidly with each blip of the throttle. Ford’s 5.2-L DOHC flat-plane-crank V8 that powered the 2016-2020 Ford Shelby GT350 Mustang was known both for its willingness to rev – redline 8,250 rpm – and its captivating exhaust snarl.

Examples of contemporary cross-plane (GM LT4 on left) and flat-plane (Ford 5.2L) V8 crankshafts showing arrangements of crank throws. (GM; Ford)

Road-car engineers, especially those at Ferrari, relish transferring these technical advancements from the track to the street. Before turbocharging and hybridization were adopted at Italy’s renowned sportscar maker, their smallish V8s employed flat-plane crankshafts to produce both exemplary horsepower and a rousing exhaust shriek. With their modest displacements, second-order shaking was less an issue.

A Ferrari V8 aural “soundtrack” is more exhilarating than those of American V8s because their smaller piston displacement allows them to rev faster to higher rpm. Also, the exhaust pulses leaving each bank of cylinders are evenly spaced.

That last attribute is key to optimizing volumetric efficiency and maximizing horsepower. In the cross-plane crankshaft 6.2-L V8 powering the 2022 Corvette Stingray, the firing order is compromised with the third cylinder in the left bank firing immediately after the first cylinder in that bank. That means there is only 90 degrees of crank rotation instead of a Ferrari V8’s 180 degrees between those two exhaust pulses. This diminishes the scavenging benefit resulting from the flow exiting one cylinder helping to draw exhaust out of the next. It’s also easier to optimize intake airflow when each cylinder bank draws a breath every 180 degrees of crank rotation.

Flat-plane LT6 only the start

With dual overhead cams, four valves per cylinder and variable intake and exhaust timing, SAE-rated output for the upcoming flat-plane-crank LT6 should top 600 hp (447 kW) at an estimated 8000 rpm and 450 lb-ft (610 Nm) at 6000 rpm. Experience gained racing the Corvette C8R powered by a flat-crank 5.5-L DOHC V8 for two seasons in the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar series has expedited development, confirms a senior engineering executive at GM Propulsion who was not permitted to speak on the record.

There’s more. Informed speculators insist there’s an LT7 engine next in line to power the 2024 or 2025 Corvette ZR-1. This twin-turbocharged variant of the flat-crank 5.5-L V8 should up the ante to at least 850 hp (634 kW) and boost torque to around 800 lb-ft (1085 Nm). And following Ferrari’s astute lead toward hybridization, two Corvette hybrids also are on the way. Second-order vibration be damned.

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance