New Rules Shuffle the F1 Deck

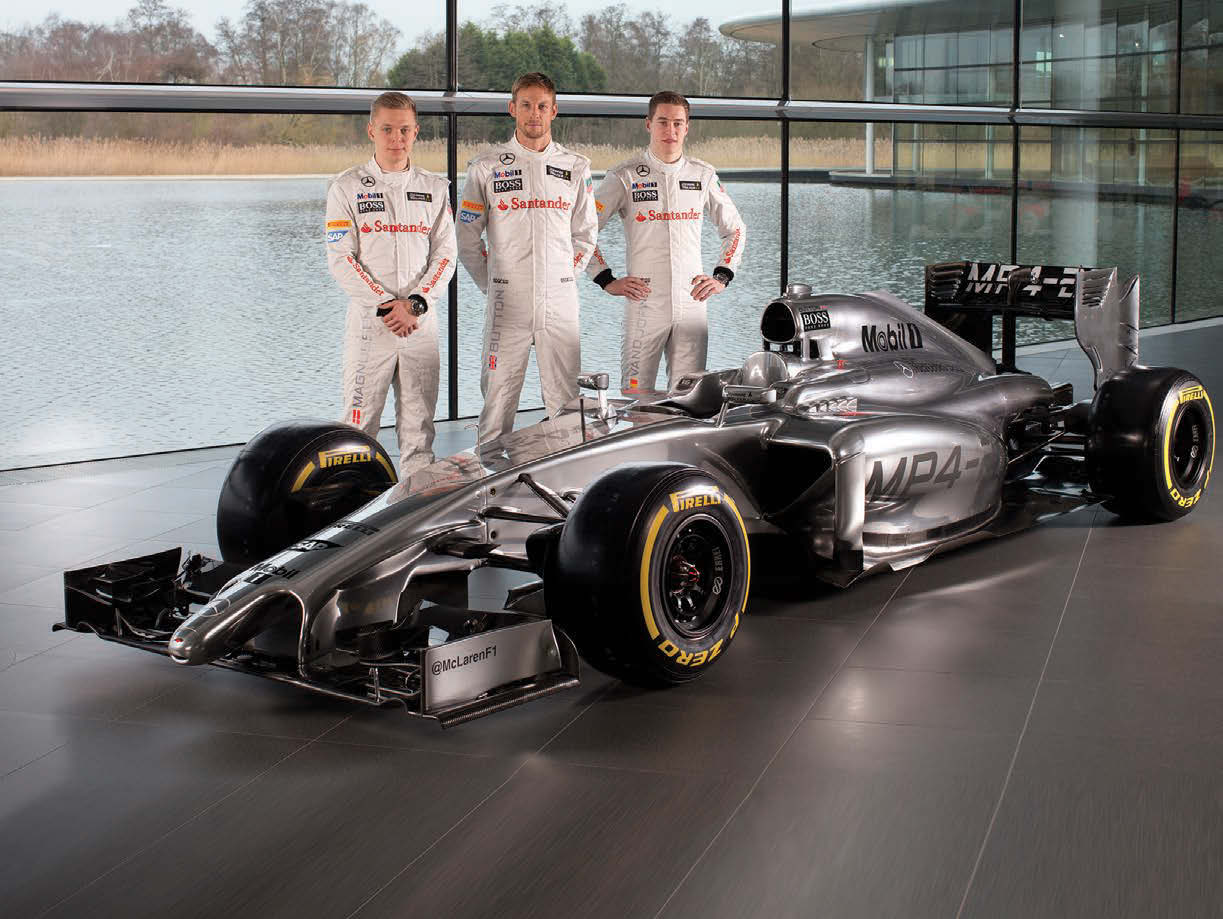

New turbocharged hybrid-electric power units and revised aerodynamics may scramble the familiar order in Formula One for 2014.

This season will see an almost entirely new slate of rules for Formula One that effectively make it a different series. The cars are changed aerodynamically and have dramatically different power sources. Stiff limitations on track testing, wind tunnel testing, and even CFD modeling aim to limit costs and reduce the advantage bigger-budget teams hold over smaller teams.

Championship points will be allocated differently (double points in the last race), and there are two new circuits on the schedule.

The scope of the change will, itself, affect the course of the season, as teams encounter reliability problems stemming from the newness of their equipment, and as relative performance changes as some teams make bigger gains than others from one race to the next.

Ferrari Technical Director James Allison ruminated on what the changes have meant for Formula One engineering staffs and what they will mean to competitors this year.

“2014 sees us, for the first time in many years, have free development of the engine from a clean sheet of paper,” he said. “For sure that’s going to bring a level of variation of power between the various engine manufacturers. It makes the engine a much more important competitive factor in 2014 than it has been in recent years.”

Similarly, the new aerodynamic rules will also create winners and losers. “The rate of development we have aerodynamically through the season will be very steep, and the importance of aerodynamics to the championship will be at least as important as the differences in the power levels of the various engine manufacturers,” Allison asserted.

“However, if I had to choose a thing that was likely to be the dominant factor for the whole season, I would choose neither the level of power nor the aerodynamic development. I would say this year reliability is going to be absolutely fundamental.”

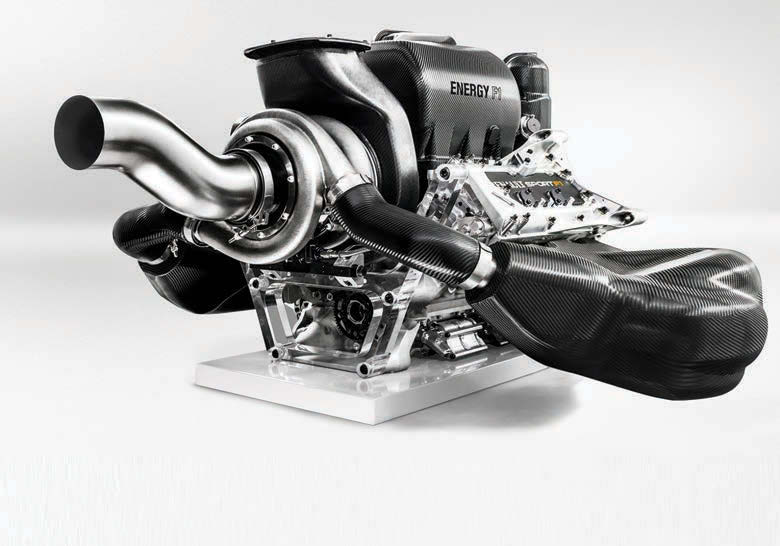

Turbo V6 hybrid power unit

Perhaps the single largest change for the new season is the replacement of the 2.4-L normally aspirated V8 engines employed since 2006 with an all-new 1.6-L turbocharged V6 engine. This engine is further restricted to a maximum of 15,000 rpm, rather than the 2013 rev limit of 18,000 rpm. Turbo speed is limited to 125,000 rpm.

For the first time, there is a fuel limitation. The engine can consume fuel at no more than 100 kg/h, and the car may carry only 100 kg (220 lb) of fuel for the race, placing an emphasis on fuel efficiency over power.

Previously, fuel flow was unrestricted, as was fuel capacity. Teams typically built cars with a capacity of 160 kg (350 lb) of fuel. The V6s are 90° type by mandate in the new rules.

To make up for the lost horsepower of the smaller, slower-turning engine, the internal-combustion engine is supplemented by an Energy Recovery System (ERS), which is a stronger replacement for the previous Kinetic Energy Recovery System (KERS).

“It is much more than just an engine change; it is a completely different system,” observed Williams Chief Technical Officer Pat Symonds. “We’ve gone from a slightly hybridized normally aspirated engine to a fully integrated hybrid power unit with novel technology at its heart.”

Strong hybrid

That hybrid-electric assist now adds 160 hp (119 kW), double the 80 hp (60 kW) of the previous system. Further, it can be used for 33.33 seconds per lap, rather than the 6 s last year. An interesting byproduct of this extra power and time is that it consumes more electrical power — 4 MJ per lap — than the 2 MJ that can be recovered over the course of a lap, so it cannot be used at full power every lap. Instead, drivers will have to marshall their accumulated electric power, accumulating it for use in an attack.

Energy is recovered through the Motor Generator Unit-Kinetic (MGU-K) the usual way: by converting the car’s kinetic energy to electric power stored in the 20- to 25-kW·h lithium-ion battery pack. Additional power comes from the electric motor/generator connected to the turbo-charger. This is the Motor Generator Unit-Heat (MGU-H).

It works by converting the spinning turbo’s energy into electric power to charge the battery. It also serves to limit the turbo’s maximum speed and to prevent it from slowing down. By accelerating the turbine with electric power, the cars will have no turbo lag whatsoever. Interestingly, the Sauber team further notes that it is technically possible and permissible for the MGU-H connected to the turbocharger to directly supply electricity to the MGU-K that helps propel the car, providing additional electric-assist beyond the specified 33.33 s.

Sauber uses a power unit provided by Ferrari, so the Prancing Horse’s car will likely reflect the same capability, even if other teams do not have this capacity built into their cars.

In total, the hybrid-assist system will trim lap times by more than 2 s, according to McLaren Mercedes. That compares to a boost of only a few tenths of a second per lap for the old KERS system.

The mass of the complete power unit is specified as at least 145 kg (320 lb), compared to 95 kg (209 lb) for the old engines. Correspondingly, minimum weight for the entire car with driver has also risen, to 690 kg (1521 lb) from last year’s 642 kg (1415 lb).

The new power units’ total output is predicted to top that of last year’s engines, potentially making the new cars faster.

“We have measured power-unit performance on the testbed and have matched the most optimistic predictions,” noted Renault Sport F1 Deputy Managing Director Rob White. “We believe the power unit will deliver a lot of power and will be more than enough to make the cars quick.”

V6 combustion power

The new V6 engines will make more low-end torque, supplemented by the torque of the electric-assist motor, for stronger low-end acceleration, while the restricted fuel flow will flatten power at higher revs — revs that will cut off at a lower speed than before.

“The way that the cars deliver this performance will be somewhat different this year due to the power unit and aero regulations,” White said. “The driving experience will be quite different, but we will absolutely see real speed out on track.”

The question of success in the championship, then, will likely come down to reliability, as Ferrari’s Allison speculates. Integrating so many disparate new systems invites the unexpected. Even the thoroughly understood KERS systems suffered regular failures. But those failures handicapped the affected cars only slightly. Now, a failure of the hybrid-assist system will wreck a driver’s race as the car loses seconds per lap to rivals.

Matched to the new power unit is a new eight-speed gearbox. This reflects one more gear than teams used in 2013, but now teams cannot change the ratios of those gears from race to race. For 2014 alone, teams will have the ability to change their ratios once, to correct any preseason miscalculations. That will be the only change allowed.

Gearboxes must last six races each before they are replaced, and teams are allotted five power units for the season. Premature replacements of these parts will inflict dire penalties on the drivers’ qualifying positions, which will undercut their ability to score top championship points in the ensuing race.

Aerodynamics revised

The 2014 cars’ appearance differs because the rules specify lower noses in a bid to minimize the chance of cars overriding one another in collisions. Now the front end may be no higher than 18.5 cm (7.3 in), compared to the 55 cm (21.7 in) allowed before. Meanwhile, the front wing has been narrowed to 165 cm (65.0 in), from 180 cm (70.9 in), dramatically complicating airflow around the front wheels.

Inside, the chassis’ construction has been influenced by the addition of longer, triangular-section impact-absorption tubes that contribute side-impact protection for the driver. The Infiniti Red Bull Racing team takes credit for designing these new structures, which are standardized and incorporated into all teams’ cars.

Sidepods have grown because of the need to cool all the new systems and devices aboard.

“Overall, the cars will need more cooling this year,” remarked Symonds of Williams. “The demands on water and oil cooling may be slightly diminished, but the ERS system is significantly more powerful and hence needs more cooling. We also have to cool the charge air from the turbo-charger compressor, which requires a substantial intercooler.”

The Sauber team reports that additional packaging space was also needed for all of the electronic boxes. The team’s Sauber C-33 Ferrari racecar incorporates more than 40 such electronic boxes, and more than 30 of those require cooling, according to the team.

Bringing up the rear

At the rear of the car, rules have specified that the engine’s exhaust will depart from a single pipe at the car’s centerline, aft of the bodywork. This is a common configuration in lower-category Formula cars, so it is a familiar appearance to racers, but it is new to Formula One. The purpose is to eliminate the use of exhaust gases to increase aerodynamic downforce, as was done with the previous “blown diffusers,” which saw exhaust gas pouring onto the top of the diffuser to increase the pressure differential with the air underneath.

The rear wing has traditionally incorporated a lower horizontal element for a biplane wing, but the lower element has been eliminated. The upper element is now supported by its end plates, which extend downward to mount to the rear bodywork.

The 2014 cars’ rear brakes are now brake-by-wire, so that a computer can negotiate the compromise between regeneration braking and friction braking to best slow the car and recover energy.

A new restriction on the teams doesn’t affect the cars’ appearance or their initial performance, but could mean cars at the end of the season that aren’t as fast as they could have been. To help smaller-budget teams keep up with the juggernaut teams, wind tunnel testing is limited to 30 hours per week and CFD number-crunching is limited to 30 TB of data per week. The thinking is that it helps cap costs and contributes to quality of life for team members who only need to work during civilized hours.

In total, the shuffling of the rules has motivated the sport’s engineering teams, said Allison.

“That, for an engineer, is like Christmas every day. This year we’ve had the additional pleasure, from an engineering perspective, of being able to start with a clean sheet of paper, a completely new project — a complex and difficult project. And to be able to design from nothing the entire layout of a very difficult and complex car.”

What could be better?

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...