F1 Streamlines for Closer Racing

In the downforce vs. turbulence battle, Formula 1 enacts technical changes to rev up the on-track spectacle.

Ongoing aerodynamic development of Formula 1 racecars has the most obvious goals of increasing the cars’ downforce and reducing their drag to produce the fastest speeds and quickest lap times.

But there is another, perhaps cunning, reason behind the work being conducted in wind tunnels and in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) tools: to degrade the aerodynamic performance of competitors’ cars and their ability to benefit from slipstreaming. Some of this degradation is inevitable, of course — it’s caused by the turbulent “dirty air” produced by a race car’s wings, tires and underbody aerodynamics.

But when designers can find methods to make a car’s wake less advantageous to pursuers by reducing their cars’ downforce, they will do so — if it doesn’t slow their own car.

Since the current generation of hybrid-electric Formula 1 cars debuted in 2012, the racing has been substantially processional, with every championship won by Mercedes-AMG drivers. Fans have complained about this—and about the hybrid-electric cars’ decidedly uninvigorating sound.

New rules

In response to these concerns, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile is plotting a clean slate of new specifications for the 2021 season, aimed at improving the spectacle. But race fans are unhappy now, so the FIA has tweaked the rules for the upcoming season in a bid in increase the opportunity for cars to race nose-to-tail.

“The front wheels of an F1 car produce a very dirty wake and teams naturally want to push it to the side to get nice, clean air flowing over the rest of the car,” explained Formula 1 chief technical officer Pat Symonds. “They do this by producing specific vortices with the front wings and brake ducts. If you look at the current front wings, there are a lot of appendages and elements sitting on top of the wing. Each one is designed to produce a vortex, to control that wake.

“Unfortunately, when you start pushing the front wheel wake out a long way, you create a very wide area of low-energy air behind the car, which reduces the downforce on the following car,” he noted.

Starting at the front of the car, 2019 rules dictate a wider, 2,000-mm (78.7-in.) front wing in place of the 1800-mm wing (70.8-in.) wing used in 2018. The front edge of the wing also is moved forward 25 mm (.98 in.), while the stack of winglets atop the main plane is raised 20 mm (0.8 in.).

All of these changes are meant to help provide the car aerodynamic downforce even when the in the degraded dirty air directly behind another car, letting the pursuer closely follow the target car through a turn in preparation for a pass on the ensuing straight.

The 2019 front-wing rules also ban the array of turning vanes seen atop 2018 wings that vector airflow around the front tires. The vanes’ purpose is drag reduction, but they also have the effect of disturbing the air more for following cars. Eliminating them should let pursuers follow more closely.

Beneath the front wing, 2018’s row of five longitudinal strakes is reduced to only two for 2019—also limiting the wing’s ability to steer the air away from the front tires.

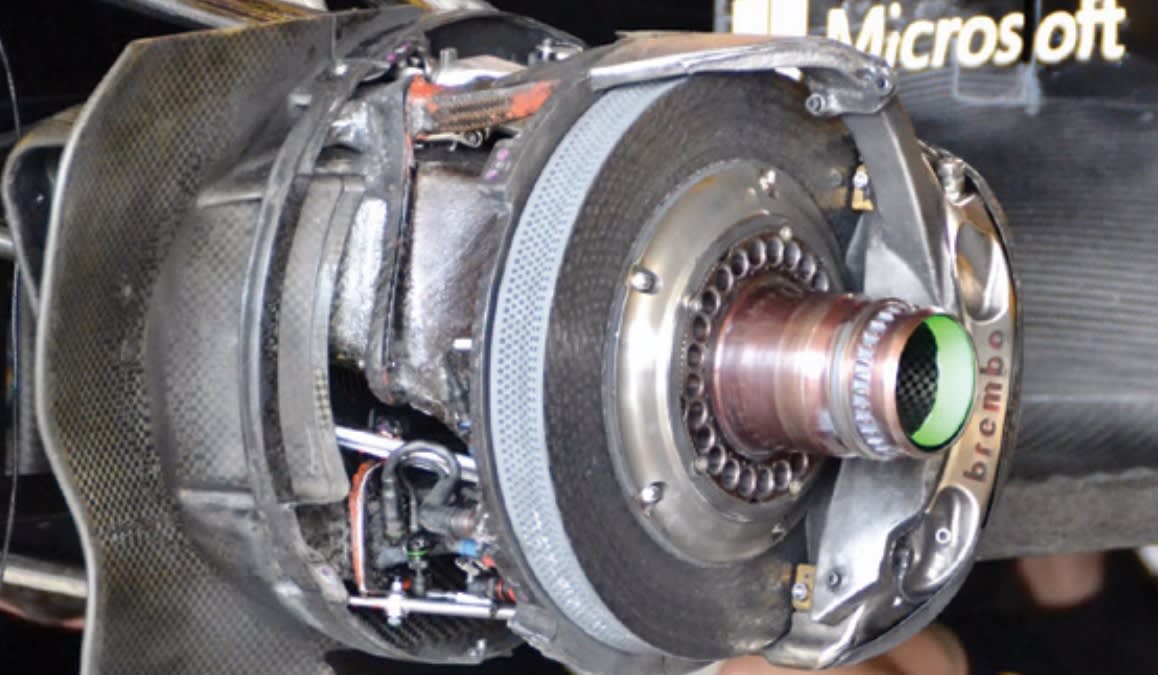

The air intake ducts for the front brakes are smaller for 2019. That’s because the 2018 ducts were larger than necessary for brake cooling. Their excess air diverted through hollow “blown” axles that pushed airflow away from the spinning wheel. That enabled drag to be reduced while disturbing the air for trailing cars, too.

And so it is for the barge board turning vanes ahead of the sidepods. For 2019, these must be 150-mm (5.9-in.) shorter, top to bottom, but are permitted to extend another 100-mm (4-in.) closer to the front wheels. This reduces their ability to control airflow to the rear wheels.

Bringing up the rear

The rear wing is 100-mm wider, 20-mm taller and has end plates that are 70-mm (2.7-in.) longer. The Drag Reduction System (DRS) slot between the upper element and the main plane of the rear wing is 20 mm larger, making it about 25% more effective in reducing drag when the slot is open during passing opportunities on high-speed straights. Pressure-equalizing slots in the tops of the end plates are also eliminated for 2019.

The DRS has been criticized for creating “artificial” passing opportunities. Its necessity is being reconsidered as the FIA studies options for the further - reaching 2021 rules, which could produce cars that permit more organic racing and passing.

“The rear wing helps us when we’re trying to promote closer racing,” said FIA aerodynamicist Nikolas Tombazis. “It has two strong trailing vortices, which pull the flow up from close to the ground into the ‘mushroom.’ This mushroom is pushed upwards quite violently and quickly, allowing clean air to be pulled in from the sides to take the place of the turbulent air being flung upwards.

“This clean air tends to be higher energy, which has a beneficial effect on the aerodynamics of the following car,” he continued. “We want to increase that mushroom effect and make it stronger, but also put more of the dirty air into its vicinity to push it up and out of the way.”

Safety, fuel and engines

The new rear wing also incorporates rain lights to enhance the cars’ visibility through the spray of a wet race. The central light used until now remains.

Another aid to racing for 2019 is an increased fuel allotment — 110 kg (242.5 lb) of fuel in place of 105 kg (231 lb) for each race. This will let drivers keep the engine’s power turned up through the whole race, rather than limping along in fuel-saving mode to avoid running out of gas in the closing laps.

The F1 racecar’s minimum weight without fuel is increased, from 733 kg (1,616 lb) to 740 kg (1,631 lb). Significantly, for larger-sized drivers, this weight includes an 80-kg (176-lb) allotment for the driver. Heftier pilots no longer have to diet like jockeys to preserve maximum performance. Lighter drivers are obligated to ballast their cars to the 80-kg total; the ballast must be placed in the area of the seat and not somewhere else in the car that could be advantageous for performance.

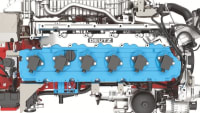

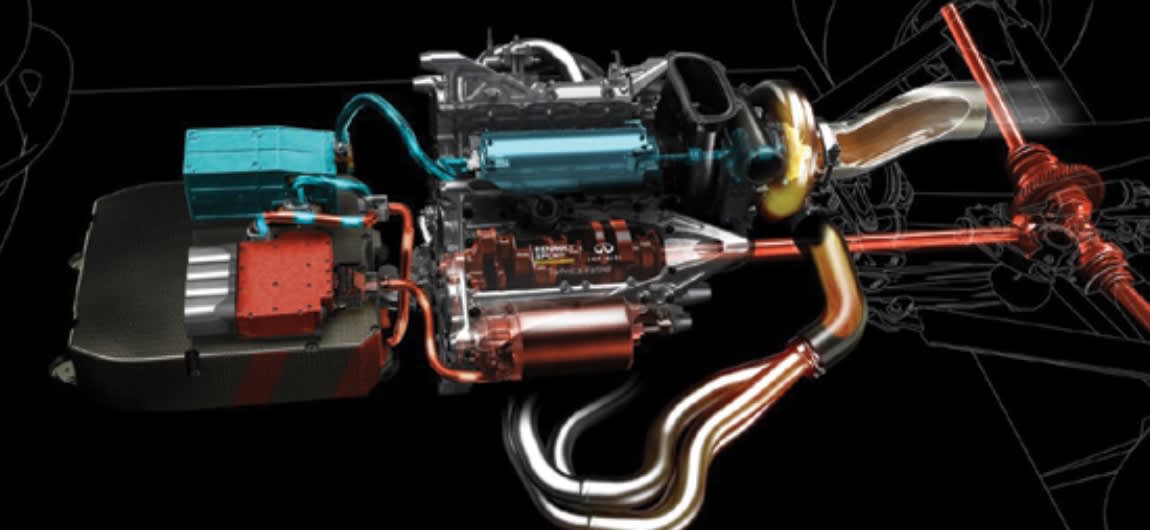

In terms of propulsion-system changes for 2019, the Renault F1 team has discarded the internal-combustion portion of its 2018 power unit in favor of an all-new 1.6-L 90-degree turbocharged V6. While strict rules, such as a 15,000-rpm rev limit and four-valves-per-cylinder maximum constrain the potential scope of changes, the old engine’s potential for improvement wasn’t enough to help the team achieve parity with Mercedes and Ferrari. So, Renault designed an all-new engine for this year, said managing director Cyril Abiteboul.

To that end, the team is expanding its engine facility in Viry-Chatillon, France, with a new test bench that will let Renault do more all-up testing of track-ready drivetrains. Their goal is to detect problems that might have previously arisen only at the race circuit.

“The idea is to make another step forward in terms of validation, with as many components that will eventually run on track as possible, shortly before the car itself actually runs”, said Laurent de Bailleul, Renault’s head of testing equipment development, in remarks provided to Automotive Engineering. “This final stage of validation allows for better preparation before the first test. That’s the real potential.”

“With as many elements as possible, it’s more representative. It’s another step compared to how we already start the engine at the factory to make sure the car can actually start and run some laps.” Previously, the team could only find out about ‘engine and chassis’ issues, and precisely calculate fuel consumption, while on track.

Closer racing for 2019?

All of the F1 teams hope for closer racing this year. But it remains to be seen how effective the rules changes will be in the face of ongoing technical development by teams...to overcome the limitations of the rules.

“We consider the critical position to be around 15 to 20 meters between the cars,” the FIA’s Tombazis said. “That’s the distance we’d expect to see between cars running half-a-second apart approaching a medium-speed corner. With the current generation, the following car loses about 30 percent of its downforce in this scenario. We hope to reduce that by 10 percent.”

He noted that the general trend for teams is to develop more downforce, which exacerbates the problem. “We now believe that 2019 will be better than 2018, but no one is expecting F1 cars to be fighting like touring cars.”

Williams F1 chief technical officer Paddy Lowe agrees. “I feel that not doing anything now would mean we’d have several years of a worsening situation as the teams develop more downforce,” he said. “I’ve got quite a high confidence in the technical aspects of what’s been done, that it will take us back in the right direction.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...