Fuel-Economy and Greenhouse-Gas Emissions Rules Debated

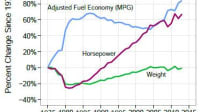

The passenger vehicle and commercial vehicle industries are working to meet government regulations for emissions and fuel economy while ironing out potential unintended issues.

CAFE (corporate average fuel economy), greenhouse gas emissions, and zero-emission-vehicles mandates from NHTSA (U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration), the U.S. EPA, and CARB (California Air Resources Board), respectively, are keeping engineers and product planners busy.

“Government can affect what consumers do with taxes and incentives, and government can affect what automakers do with rules, regulations, and incentives,” Robert Bienenfeld, Assistant Vice President, Environmental and Energy Strategy at American Honda Motor Co., Inc., intoned to an SAE 2014 World Congress audience in Detroit.

Bienenfeld was one of the panelists participating on the "Regulatory Driven Impacts On Powertrain" program in the AVL-sponsored ballroom at Cobo Center on day two of World Congress activities.

“We would all like to see that regulations be fair amongst consumers and that they be fair amongst automakers and be fair to society, meaning the rules should achieve the desired social benefits without unintended consequences,” Bienenfeld said.

Fuel-economy regulations for passenger cars are fair, according to Bienenfeld: “They allow customers to choose the cars freely, and automakers can compete within their segments. The regulations are indifferent as to what technologies we apply. And there’s an enormous amount of innovation with literally dozens of technologies competing on a relatively fair battlefield.”

But Bienenfeld’s words were less flattering when he gave his evaluation of fuel-economy mandates on pickup trucks: “What we see is that trucks have slanted regulations—more stringency for smaller trucks and less stringency for larger trucks. That’s a given. But the line should be parallel, and it’s not—at least for the next five years. As a result, it looks like large trucks are subsidized by cars and smaller trucks, which is not good for OEM competition. And frankly, it’s not the best deal for consumers either."

Christopher Grundler, Director of the EPA's Office of Transportation and Air Quality, was asked to comment on mandate fairness during the audience question-and-answer session.

“Robert and I have been arguing about this for at least three years now—this fairness question with respect to trucks," he said. "Of course, fairness is dependent on where one sits. The honest answer is that the manufacturers of large trucks were pretty convincing at the end of our collaboration of creating these standards that they would not be able to meet the same pace of improvement as passenger cars.

“So we changed the slope in the early years to respond to the data and the arguments they presented. So is that unfair? Obviously unfair to Honda, which doesn’t make those large trucks. For the people who do make those large trucks, they thought it would be unfair if we didn’t make this change.”

Production of Honda’s only full-size pickup model ends in mid-2014. An all-new Ridgeline pickup truck will reach the marketplace in less than two years.

Another regulation affecting passenger vehicles requires automakers to deliver a certain number of ZEV credits (via some portion of plug-in hybrid vehicles, battery-electric vehicles, or fuel-cell vehicles) as a percentage of sales. In addition to California, the ZEV mandate has been adopted by the states of New York, New Jersey, Vermont, Maryland, Massachusetts, Oregon, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Maine.

“And those 10 states count for more than 30% of U.S. sales. For some companies that can be as much as 40% or even 50% of sales,” said Bienenfeld.

A re-thinking of the ZEV credits as it relates to PHEVs is needed, according to Bienenfeld. “Now that there have been some (PHEVs) in the market, we can see that plug-in hybrid vehicles deliver a lot more annual electric miles than you would think,” Bienenfeld told Automotive Engineering magazine.

Government regulations are also changing the product-development landscape for commercial vehicles, which range from heavy-duty pick-up trucks, garbage trucks, and school buses to tractor-trailers.

Said Jennifer Rumsey, Cummins Inc.’s Vice President of Engineering - Engine Business: “Starting this year for the first time ever in the U.S., commercial vehicles are regulated for greenhouse gas emissions.”

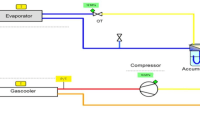

Phase one of the regulation treats the engine, which is a common component across many of the different applications, and the vehicle itself separately. “It’s a relatively simple and effective way of regulating a complicated industry, and it’s already providing benefits,” said Rumsey.

Announced in February 2014, phase two of the regulation “is intended to drive further and more significant advancements,” said Rumsey, adding, “It must address additional technologies that aren’t included in phase one, like transmissions and trailers, and consider how to capture adequately the benefits of integrating these components together.”

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...