Solving the GHG Puzzle

While automakers and policymakers debate the TAR, engineers and product planners prepare for the steep climb to meet GHG and CAFE rules beyond 2022.

When the U.S. EPA published its Technical Assessment Report (TAR) draft in July on how well the auto industry is meeting federal fuel economy mandates, as a prelude to the Mid-Term Evaluation of the 2022-2025 national program for Corporate Average Fuel Economy, voices from all sides chimed in.

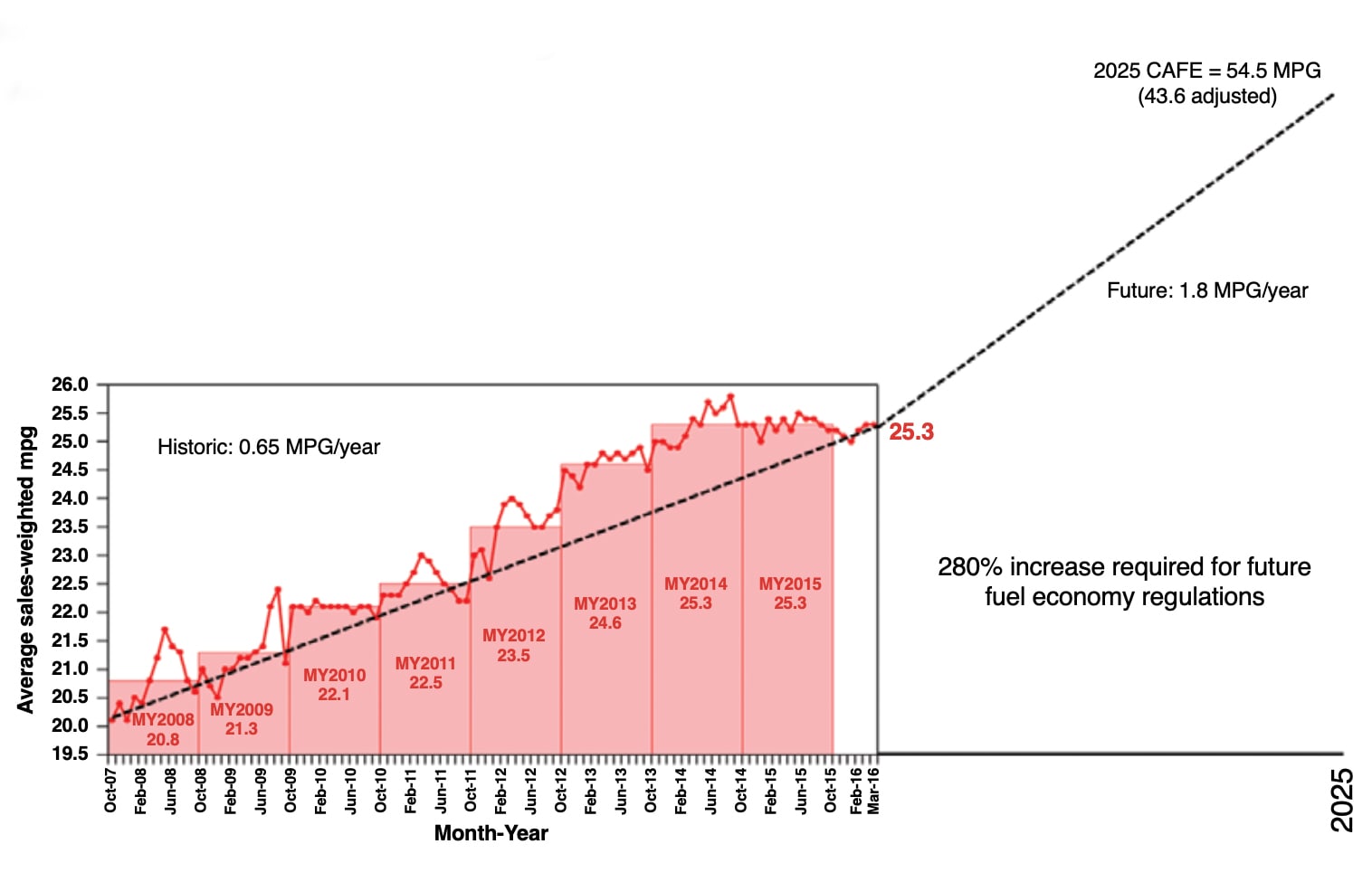

Seeing the TAR draft, some media misinterpreted it as the government backing off from its 54.5-mpg target. That certainly is not the case. Recent presentations and statements from EPA and California Air Resources Board (CARB) leaders indicate the agencies are already thinking beyond 2025. California even has some legislation to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050. Outright calls for retreat from the present course have been rare thus far, despite low retail fuel prices not expected when the current program was established in 2012.

Few industry leaders are betting that the 2025 standards will be relaxed in the Mid-Term Evaluation of progress made to date. Due to be announced no later than April 2018, the MTE determines the technical feasibility of reaching the 2025 GHG targets. (CAFE and GHG are subtly different.) Overall, OEMs broadly appear committed to stay the course — a logical path given their multi-billion investments in technologies aimed at improving fuel efficiency and reducing CO2 emissions, not only in the U.S. but also in global markets.

They also face dramatically increased fines for non-compliance, arguably making GHG reduction slightly more important than CAFE, given that it is enforced under the Clean Air Act. Violation means fines up to $37,500 per vehicle and loss of sales certificate. Penalties for CAFE were recently increased to $140 for every mpg under the standard, per vehicle (up from $55).

U.S. politics could impact the current regulations. There’s no way to discern whether the next U.S. administration will be in full accord with the last seven years of GHG-reduction efforts.

While OEMs continue wringing higher efficiency from internal-combustion engines (ICEs) and conventional drivetrains, it’s clear that more electrified vehicles will be required. Those companies already ahead of the curve are well aware that the challenges ahead present excellent opportunities to stand out in the market.

Footprints and flexibilities

Considering that CAFE plateaued for nearly three decades, the Obama administration’s much quicker “doubling of fuel economy standards to 54.5 mpg” sounds like a lofty, if not admirable, goal. U.S. fuel economy testing is sometimes criticized for being outdated, with some procedures used since 1975. But the process fundamentally does work, especially with the built-in ‘flexibilities’ that serve as incentives to adopt a variety of technologies noted below. These make the 54.5-mpg target less aspirational than it appears.

The core of these standards is a vehicle’s “footprint” — the wheelbase-times-track width equation that sets a vehicle’s fuel economy and CO2 targets. The concept is to avoid penalizing inherently less-efficient vehicles that provide more capability and to control the impact of the standards on full-line OEMs. The car and light-truck footprints are each set on curves, with smaller vehicles having more stringent targets than larger ones.

Some critics claim the footprint-based metric has been encouraging OEMs to build larger vehicles. In 2015 the average new vehicle’s footprint was 49.9 ft2 — a new record according to the EPA, and an increase of 2% (about 1 ft2) since the agency began tracking the metric in 2008. EPA acknowledges that the footprint “creep” reflects consumer demand for trucks and SUVs. Of course, all automakers largely will use conventional strategies — more efficient powertrains, lighter curb weights, more aerodynamically efficient exterior shapes and lower frictional losses — to comply with the tighter standards.

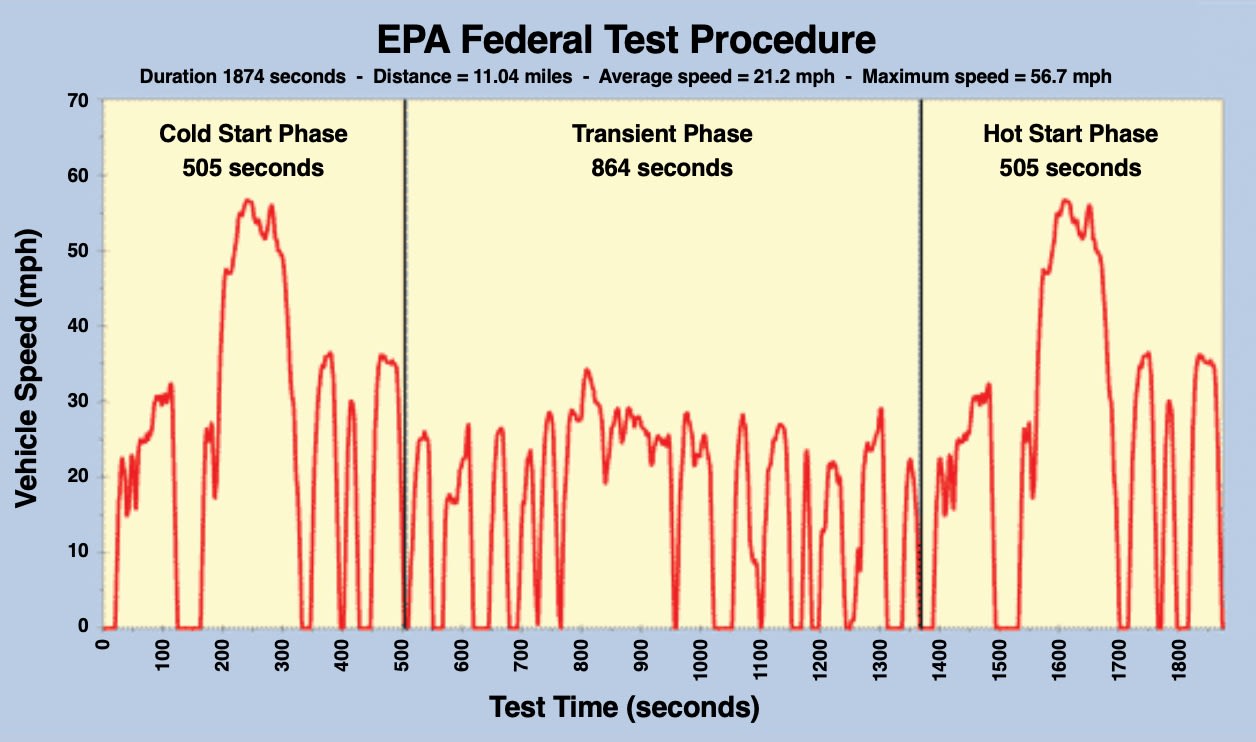

To verify compliance with the new GHG/mpg standards, the existing Federal Test Procedure (FTP or “city”) and Highway Fuel Economy Test Driving Schedule (HWFET or “highway”) test cycles carry over. This regimen is known as 2-cycle testing. Beyond the “traditional” 2-cycle standards and vehicle improvements, OEMs have a number of fuel-efficiency flexibilities at their disposal. These include:

- Electrics, plug-in hybrids, fuel cell electrics and CNG vehicles earn special “sales multiplier” factors to boost their impact, even at lower volumes.

- Consumption of grid electricity is not charged against electrics in the program’s early years (hence a BEV’s “zero-emissions” declaration).

- Flex-fuel vehicles (FFVs) earn petroleum-reduction (CAFE) and GHG credits; this flexibility is only for CAFE beginning MY16, however.

- Advanced pickup trucks employing some type of hybridization.

- A/C leakage credits — earned through the use of low global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants and reducing system leakage.

- A/C efficiency credits — improving system efficiency through a number of advanced air-conditioning technologies.

- So-called “off-cycle credits” for technologies that are not fully accounted for during typical 2-cycle testing (this flexibility deserves its own discussion — see below).

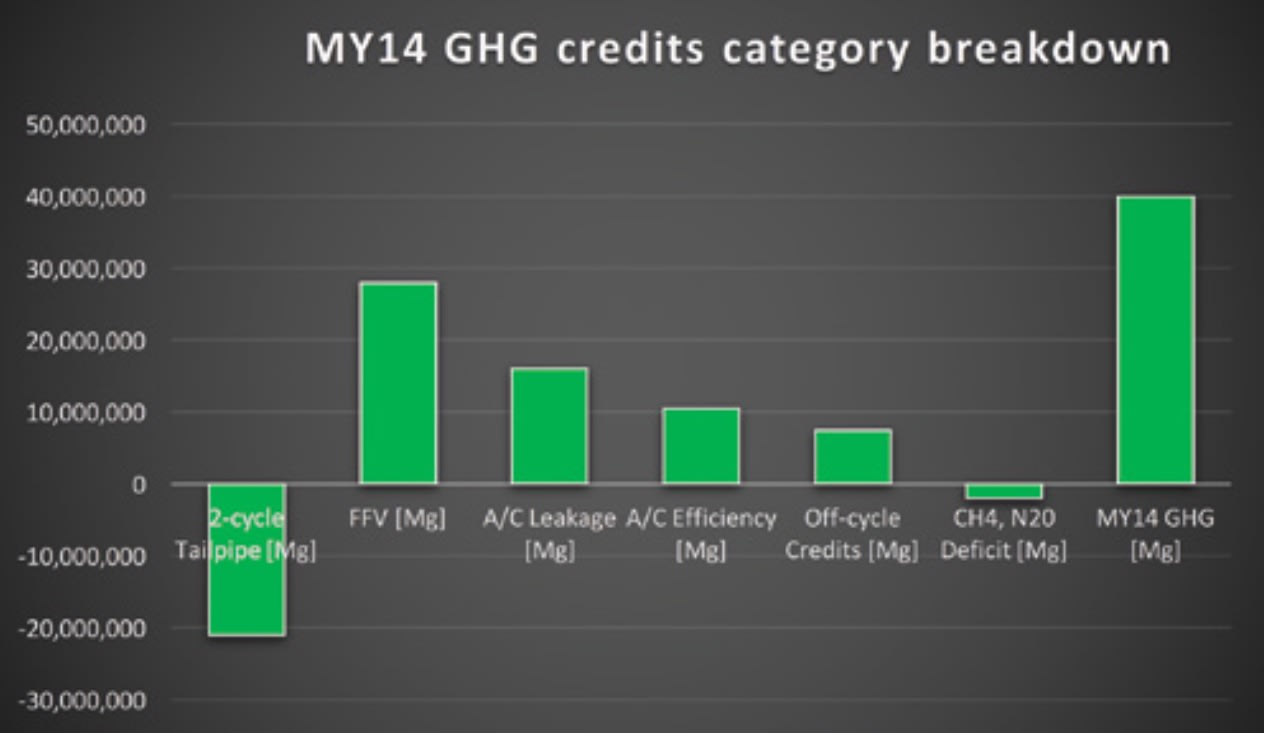

Other GHG tailpipe constituents such as methane and oxides of nitrogen (NOx) result in deficits in the new compliance methodology. Compared to CO2 their impact is small, typically less than 1%.

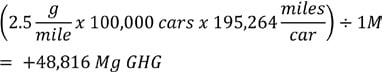

OEMs are allowed to carry a negative GHG balance for up to three years. They may purchase credits at market-determined prices from overachievers — a group of OEMs currently led by companies such as Tesla and Toyota. Compliance is determined by the equation shown here that encompasses production volume, individual vehicle or technology credits, and an EPA-defined expected vehicle lifetime miles (VLM).

Vehicle or Technology Credit [gCO2/mile]: the credit value for a specific vehicle compared to its footprint-based standard or a technology credit generated through use of a flexibility (advanced air conditioning, off-cycle credit, etc.)

Production: the total number of passenger cars or light trucks produced with corresponding 2-cycle value or technology credit.

VLM: vehicle lifetime miles is EPA-defined for passenger cars at 195,264 mi (314,247 km) and light trucks at 225,865 mi (363,495 km).

Example (2-cycle tailpipe):

Vehicle X (classified as a light truck) has a 2-cycle tailpipe emission value of 330 g/mile

Its compliance target (based on footprint) is 340 g/mile 200,000 vehicle Xs are produced annually

Example (off-cycle credit flexibility):

Engine idle stop-start is applied on vehicle Y, a passenger car Technology has an off-cycle menu credit value of 2.5 g/mile 100,000 vehicle Ys are produced annually

When accounting across an OEM’s entire fleet is complete, a positive GHG credit value [Mg] indicates compliance. Any negative balance lasting three years results in a Clean Air Act violation with the penalties noted above.

2014 model year standings

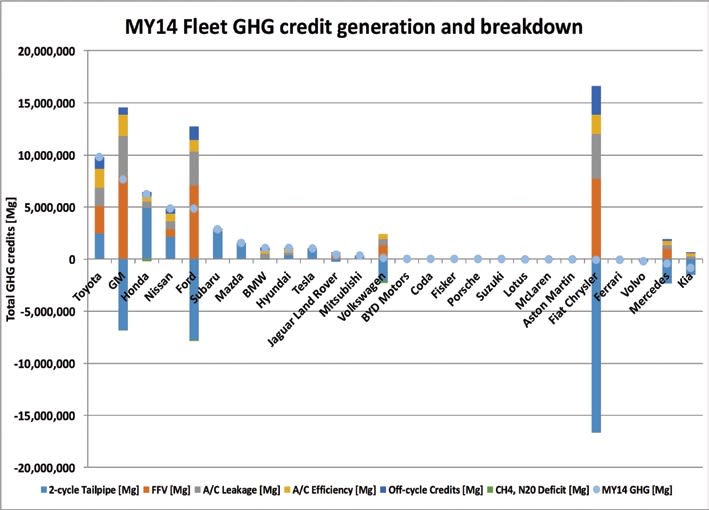

Data transparency is, according to the EPA, important to program compliance. The adjacent plot indicates the source of credits and credits generated from OEMs in MY14 (previous model-year balances are not included).

MY14 standings, not including previous-year balances, show Toyota was in the lead, generating almost 10,000,000 Mg of excess credits. Other major OEMs (GM, Honda, Nissan, Ford) follow behind. Companies like Volkswagen and FCA have a net closer to zero because their 2-cycle deficit is offset through various flexibilities.

One important aspect to note, however, is the breakdown of where these credits come from. Looking at the breakdown across the fleet, the auto industry as a whole is not keeping pace with the core metric of the regulation — 2-cycle tailpipe. The largest contributor is the FFV flexibility, which is set to expire (for GHG at least) in MY16.

The two A/C flexibilities and off-cycle credits also play a significant role. This brings a strong incentive to improve A/C systems and adopt technologies that have a high benefit in real-world use.

Off-cycle credits and credit transactions

This flexibility is a notable change from tradition because the associated environmental benefits of many technologies don’t always show up in 2-cycle testing. There are three opportunities to generate off-cycle credits:

- From an EPA-authorized menu with defined or scalable credit values

- By using the EPA’s 5-cycle testing, which includes aggressive driving (US06), hot-temperature and A/C use (SC03) and cold-temperature (cold FTP) test cycles in addition to FTP and HWFET tests.

- By petitioning the EPA for non-menu credits with a test plan and measured data. Thus far, Mercedes-Benz, GM, Ford, and FCA have used this “public process” option.

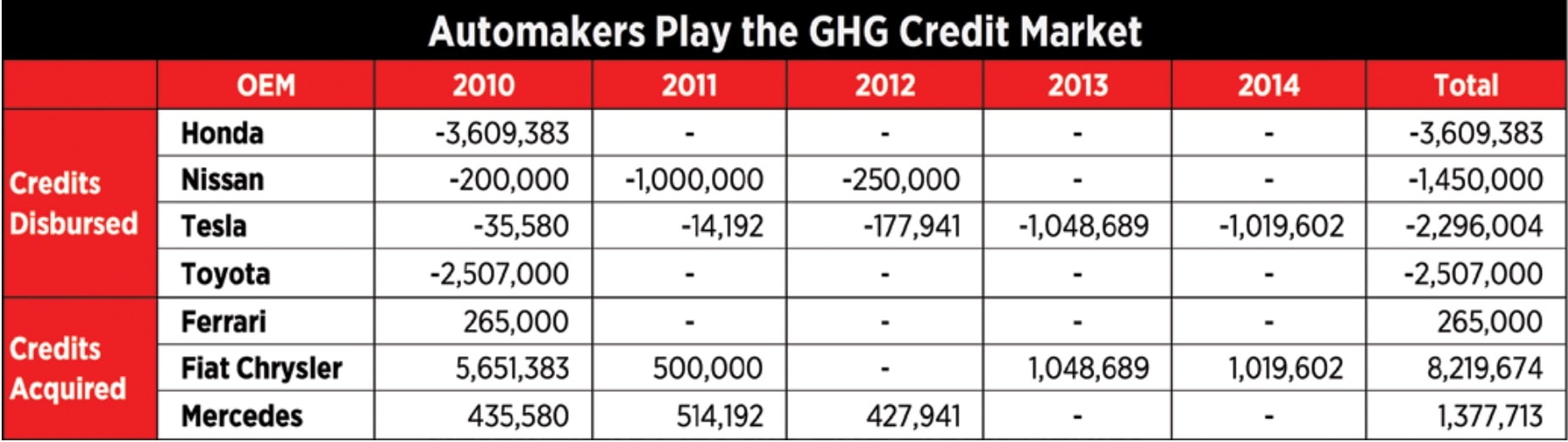

Another noteworthy flexibility is the buying and selling of GHG credits according to market-driven prices. The EPA publishes the buyers and sellers without divulging prices paid. Only OEMs may buy, sell, or hold credits. Unsold credits expire after five model years. Third parties may be used to facilitate sales.

Thus far, Honda, Nissan and Toyota have sold their surplus credits to help off-set costs associated with developing and implementing advanced technologies. Tesla also is making hay from its envious 0g/mile status — as an early-adoption incentive, emissions from grid electricity are not yet counted against plug-in vehicles.

Lower-volume makers such as Ferrari and Mercedes-Benz that sell high-margin vehicles appreciate the opportunity to purchase credits so that despite substandard overall fuel efficiency, they can maintain their reputation for delivering luxury and high performance. The high number of credits FCA has purchased in a relatively short term probably is not a sustainable long-term strategy.

The 2025 GHG challenge

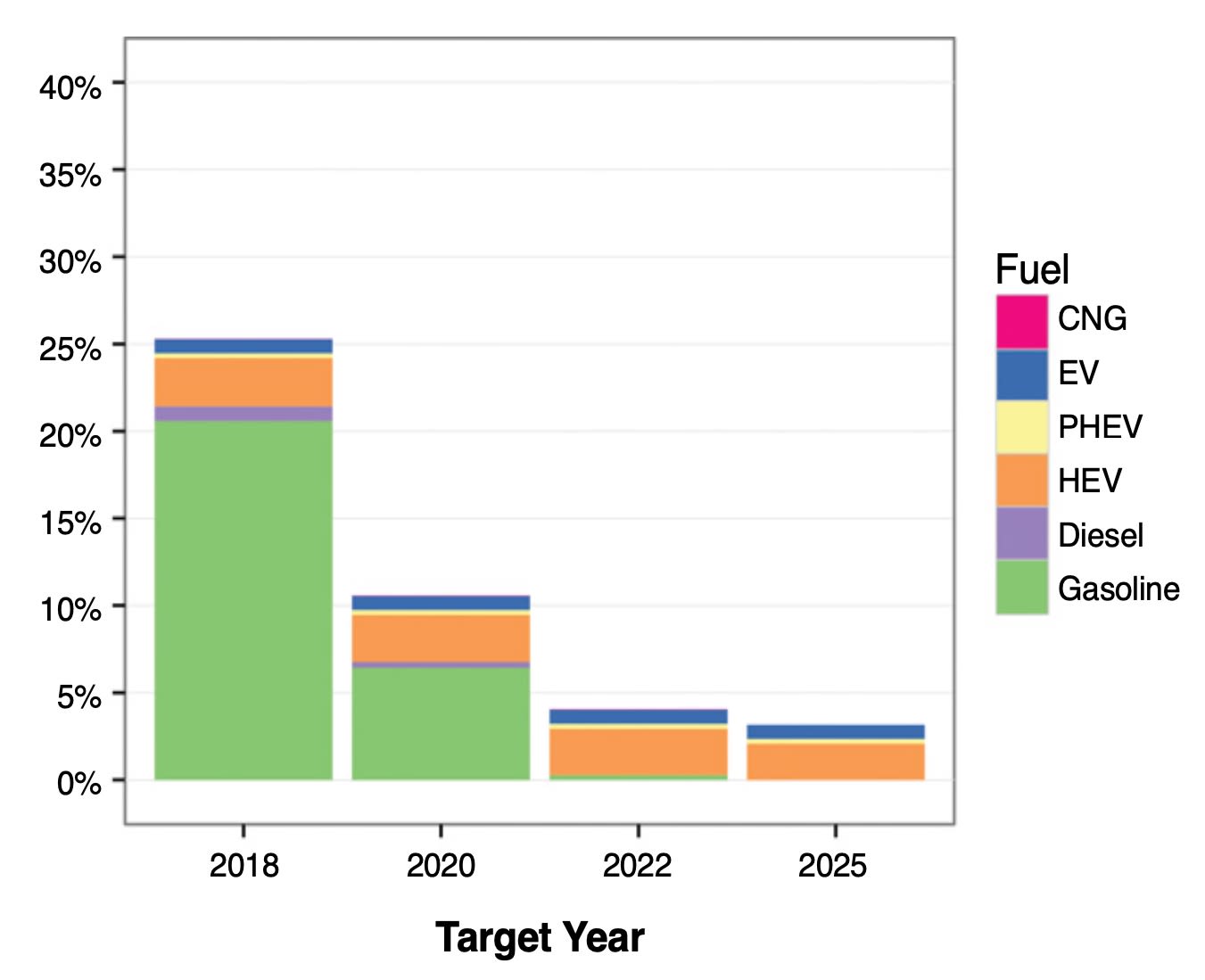

Meeting the 2025 163 gCO2/mi standard with internal-combustion engines and traditional vehicle architecture is a formidable yet admirable challenge. In truth, the U.S. market as a whole is not on pace for compliance. A nearly three-fold improvement in fuel economy and GHG reduction will be necessary.

Tellingly, of the 3% of the 2015MY fleet that meets the 2025 standards, all employ hybridization or full electrification. Not a single 2015 conventional gasoline or diesel vehicle is yet 2025 compliant. While there are still efficiency gains to come from the 130-year-old ICE, automakers must weigh their benefits in the context of greater investment and compromises (i.e., additional mass, complexity and packaging challenges).

So, while we wait for the Mid-Term Evaluation decision, R&D and product-development teams continue to focus on technology and vehicle solutions aimed at 2022-2025 compliance — the “steepest” and increasingly costliest part of the climb toward 54.5 mpg. And in roughly three months, a new administration takes up residence in Washington, D.C. How will it approach the GHG challenge — with or without a sustained market jump in fuel prices?

Regardless of these and other factors, industry engineers will deliver whatever it takes to meet the needs of customers and of the increasingly stringent regulations.

Steven Sherman is a Fuel Economy Development Engineer at the Hyundai America Technical Center, Inc. (HATCI) based in Ann Arbor, MI. A three-time University of Michigan graduate, he is passionate about solving the terawatt problem of global energy consumption. The analysis and commentary in this article are his own.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...