Selecting the Best Plastic for Spacecraft Applications

Plastic materials are used for a wide variety of spacecraft applications including seals, bearings, fasteners, electrical insulators, thermal isolators, and radomes. Selecting plastics for use in space is complex due to wide operating temperature ranges, vacuum conditions, and exposure to radiation and atomic oxygen. Additionally, some spacecraft applications require sealing flammable propellants such as hydrogen and oxygen. This article will present some design considerations when selecting plastics for use in spacecraft. It will provide rich data on the performance characteristics of plastics as well as examples of successful spacecraft applications.

Operating Temperature Range

The operating temperature range for a plastic spacecraft component may extend from low temperatures, for applications such as seals for cryogenic propellants, to high temperatures for assemblies where parts are exposed to heat from the engines. Unfortunately, material properties sheets for most plastics don’t provide rich information on their performance at extreme temperatures.

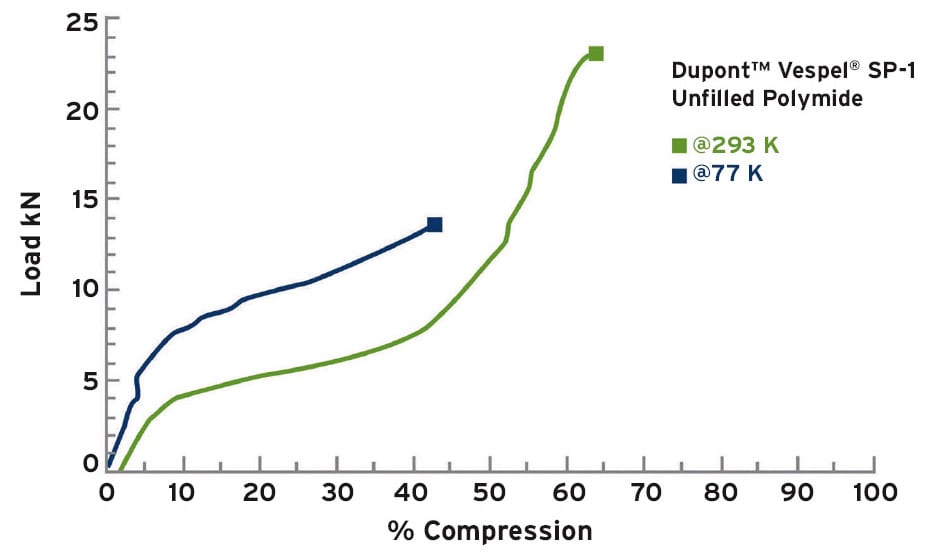

For spacecraft assemblies that involve cryogenic conditions, it is important that the plastic maintain moderate compressive modulus and some level of ductility. This is especially true for components such as seals and bearings where the plastic part needs to be soft enough to conform to imperfect mating metal surfaces. Although many plastics become brittle at cryogenic temperatures, a few materials such as polyimide maintain much of their room temperature ductility in extremely cold conditions. For example, Figure 1 shows compressive testing results for unfilled polyimide at room temperature and at 77 Kelvin. In this example, polyimide maintains sufficient ductility to be useful for a number of spacecraft applications.

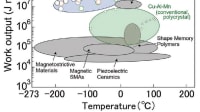

There is some complexity involved when selecting plastic materials for elevated temperature service. Mechanical properties, thermal expansion rates, creep and stress relaxation behavior, and embrittlement over time due to degradation are all important considerations.

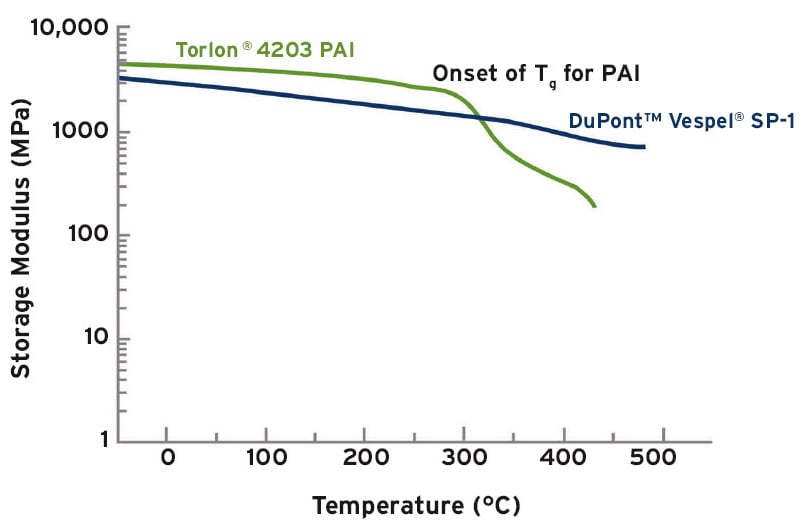

Dynamic mechanical analysis provides important information about the load bearing properties of plastics at elevated temperatures. For example, the DMA curves shown in Figure 2 compares two polymers which are often used for aerospace applications. The DMA curves illustrate that PAI (polyamide-imide) is stiffer than PI (polyimide) between 0 °C and PAI’s glass transition temperature of 275 °C, making PAI a good candidate for certain applications within this temperature range. However, above PAI’s Tg, the plastic rapidly loses its load bearing properties.

In contrast, PI maintains load bearing properties at temperatures up to 450 °C (at least for short periods of time), which is why polyimide is often selected for elevated temperature applications on spacecraft. For example, NASA qualified polyimide for use as locking elements for fasteners on the solid rocket boosters for the space shuttle at service temperatures up to 232 °C. NASA also qualified polyimide with PTFE and graphite fillers for use on the oxidizer turbine bypass valve on the Ares J-2X upper stage engine at temperatures up to 399 °C.

Oxygen Compatibility

Spacecraft systems that control the flow of oxygen require special care since plastics are a potential source of ignition in oxygen systems. When selecting plastics for oxygen service, it is important to evaluate multiple dimensions of flammability including pressure and temperature limitations, autoignition temperatures, and sensitivity to ignition from impact ( Bozet, et al., 2011, Foresyth, et al., 2000, Schoenman, 1989).

15 percent graphite filled polyimide, PTFE, and PCTFE are the plastic materials most often used for oxygen service within certain specified design boundaries. PCTFE is sensitive to molding process effects, which can result in variability of the material’s crystallinity and molecular weight. Under certain circumstances, this variability can negatively impact PCTFE’s ability to be safely used in oxygen systems. Detailed specifications, rigorous material certifications, and lot testing are important when specifying plastic materials for use in oxygen service.

Vacuum Conditions

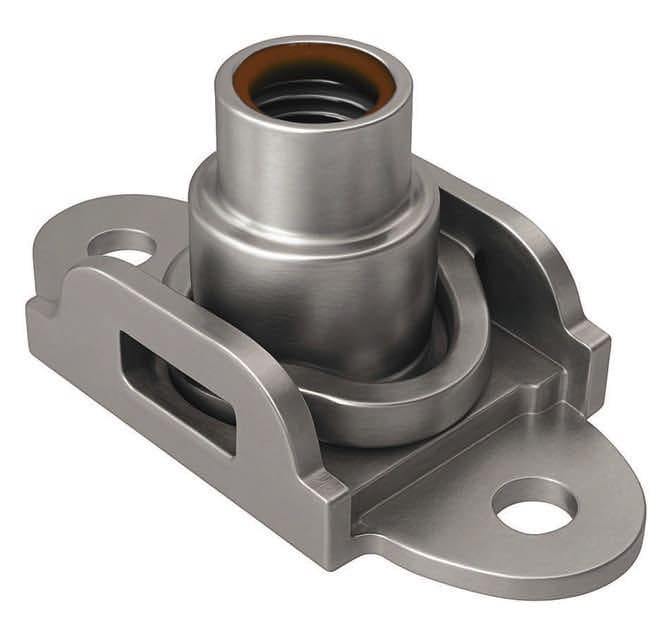

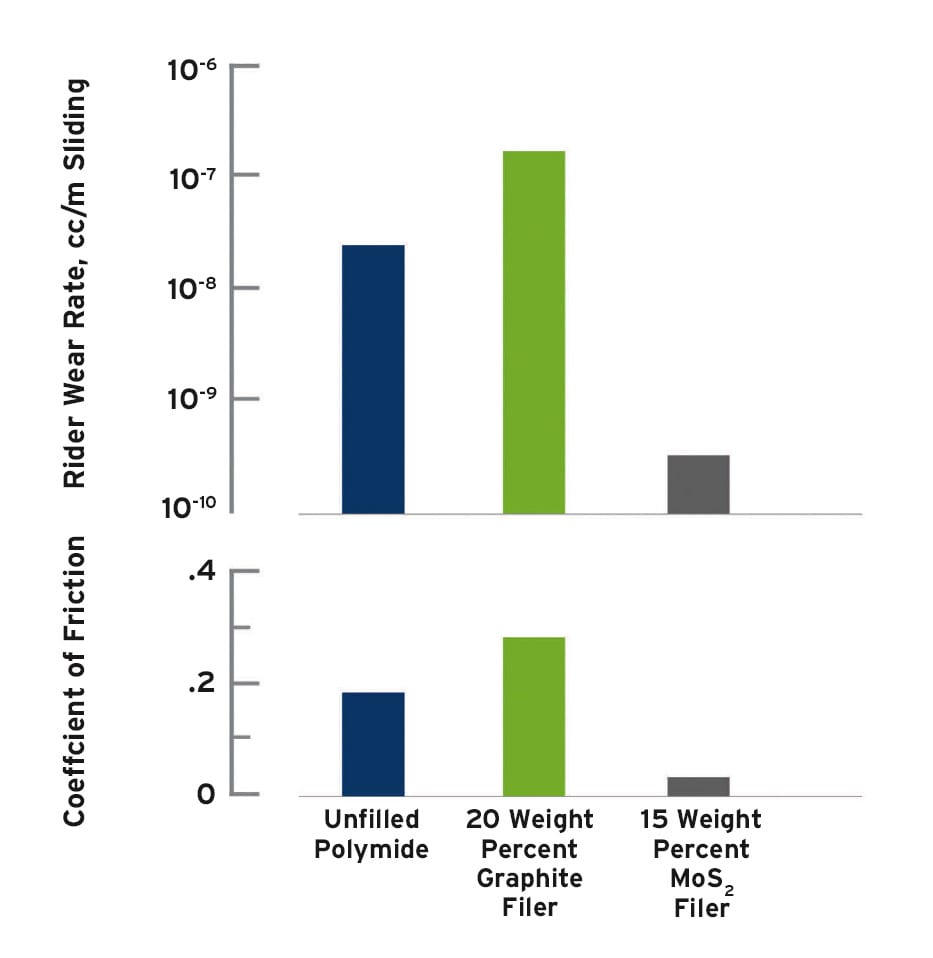

Vacuum conditions present a challenge for spacecraft design, particularly when plastic components will be in sliding contact with mating metal surfaces. Molybdenum disulfide can be an effective additive to reduce friction and extend the wear life of plastics that are used for applications such as bearings and bushings in vacuum service. For example, Figure 3 shows the low coefficient of friction and the low wear rate of molybdenum disulfide-filled polyimide compared with unfilled and graphite filled polyimide. NASA specified 15 percent molybdenum disulfide-filled polyimide for the bearing surfaces of the rotating joints on the lightweight survivable Mars rover. This reduced the mass of the assembly by 10 percent compared with traditional ball bearing designs.

Vacuum conditions require plastics with low outgassing, measured as TML (total mass loss), CVCM (collected volatile condensable material), and WVR (water vapor regained). NASA defines “low outgassing” materials as having a TML of 1 percent or less and a CVCM of 0.10 percent or less (Campbell & Scialdone, 1993). NASA’s Outgassing Database, which can be accessed online, provides TML, CVCM, and WVR values for a wide range of plastic materials.

Radiation Exposure

Plastics used for space applications may be exposed to radiation from the space environment (cosmic rays, solar electromagnetic radiation, etc.) as well as sources internal to the spacecraft including neutrons and gamma rays from onboard nuclear reactors. Designing for robustness to radiation will become increasingly important as satellites move from traditional chemical propulsion systems to nuclear propulsion. At certain radiation doses, polymers lose strength and ductility (tensile elongation). This can potentially affect plastic part performance, especially in applications that require longterm exposure to radiation. Certain plastics including polyimide, polyetherimide, polybenzimidazole, and PEEK have superior resistance to radiation compared with other engineering polymers. These materials are often specified for spacecraft applications that involve radiation exposure.

Plastic components on spacecraft in low earth orbit will erode due to exposure to atomic oxygen. NASA’s polymer erosion and contamination experiment measured atomic oxygen erosion yields for 38 polymers placed in LEO for nearly 4 years as part of the MISSE 2 materials International Space Station experiment (Banks et al., 2009). Several fluoropolymers including FEP, PFA, and PTFE exhibited low erosion yields from atomic oxygen exposure.

Some spacecraft designs include RF-transparent plastic radomes to protect communication antennas. This requires plastics with low dielectric constants and low loss factors for the frequencies of operation that are also robust to the spacecraft environment. For example, NASA used unfilled polyimide for the radome for the Mars Exploration Rover descent UHF antenna.

The purpose of this article has been to present some design considerations when selecting plastics for use in spacecraft. Readers who wish to explore this topic in greater depth are encouraged to review the articles listed in the references section. Curbell Plastics website also has technical data on the plastics used in spacecraft as well as a recorded webinar on selecting plastics for spacecraft applications.

References

- Banks, B., Backus, J., Manno, M. Waters, D., Cameron K. & Groh, K. (2009). Atomic Oxygen Erosion Yield Prediction for Spacecraft Polymers in Low Earth Orbit. NASA Technical Memorandum TM-2009-215812.

- Bozet J., Heyen, G., Dodet, C., Duquenne, M., & Kreit, P. (2011). Liquid oxygen compatibility of materials for space propulsion needs. Presented at the 4th European Conference for Aerospace Sciences (EUCASS).

- Buckley, D. H. (1966). Friction and Wear Characteristics of Polyimide and Filled Polyimide Compositions in Vacuum (10-10 mm Hg). NASA Technical Note TN D-3261. NASA Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, OH.

- Campbell, W. & Scialdone, J. (1993). Outgassing Data for Selecting Spacecraft Materials. NASA Reference Publication 1124, Revision 3.

- Forsyth, E. T., Gallus, T. D., and Stoltzfus, J. M. (2000). Ignition Resistance of Polymeric Materials to Particle Impact in High-Pressure Oxygen. In Flammability and Sensitivity of Materials in Oxygen-Enriched Atmospheres: Ninth Volume, ASTM STP 1395, T. A. Steinberg, B. E. Newton, and H. D. Beeson, Eds., American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA.

- Kane, P. & Bloom, J. (2004). Dimensional Stability and High Frequency Properties of Polymeric Materials for Machined Test Sockets. 2004 BiTS Burn in & Test Socket Workshop.

- McDonald, P. & Rao, M. (1987). Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Vespel® at Low Temperatures. Proceedings from the International Cryogenic Materials Conference, Saint Charles, IL, 14-18 June, 1987.

- Schoenman, L. (1989). Orbit Transfer Rocket Engine Technology Program. Contract NAS 3-23772, Task Order B.5. NASACR-182195. Final Report Oxygen Materials Compatibility Testing. Prepared by Aerojet Techsystems Company for NASA Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, OH.

This article was written by Keith Hechtel, DBA, Vice President of Business Development & Marketing, Curbell Plastics, Inc. (Orchard Park, NY). For more information, contact Keith Hechtel, at

Top Stories

NewsRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsPower

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

ArticlesAR/AI

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Automotive

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Automotive

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Energy

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance