Using Ultrabright X-Rays to Test Materials for Ultrafast Aircraft

This might seem like an obvious statement, but designing an aircraft that flies at five to seven times the speed of sound is difficult. Paradoxically, materials for hypersonic aircraft must be light and thin while also withstanding extraordinary pressures and temperatures. Engineering such materials is one thing but testing them under the actual conditions they would encounter on a hypersonic flight is quite another.

A group of researchers from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University is working to crack this conundrum. In partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory, the research team is in the midst of designing a device that will reproduce the extreme heat fluctuations and stresses of hypersonic flight. The device will work in tandem with the ultrabright X-rays of the Advanced Photon Source (APS), a DOE Office of Science user facility at Argonne, to track the changes that occur in these materials as they happen.

“Recreating the environment of hypersonic flight can be complicated,” said Seetha Raghavan, Professor of Aerospace Engineering and a co-principal investigator on the project. “There are so many factors and no perfect way to test them all. High enthalpy wind tunnels that can simulate the wind speed use a lot of energy resources and are limited in access.” Enthalpy refers to the heat content of a system at constant pressure.

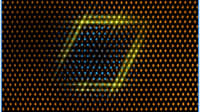

The research team’s goal is an alternative that replicates hypersonic flight conditions using fewer energy resources and uses APS X-rays to capture detailed data. The APS is in the final stages of an upgrade that increased the brightness of its X-ray beams by up to 500 times. It is now the brightest synchrotron X-ray facility in the world, and according to Raghavan, the enhanced capabilities of the upgraded APS are crucial to this project.

“When you are talking about hypersonics, you’re talking about high speeds and fast changes, and response time is critical,” she said. “You can only get that kind of time resolution with enough flux (or brightness of the beam), and the upgraded APS is able to help with that.

“Additionally, the materials we’ll be testing are the thinnest that can be used, and at the upgraded APS you can focus the beam down to a small enough size to capture the data we need,” she said.

Victoria Cooley, an APS beamline scientist who worked with the Embry-Riddle team at beamline 1-ID, touted both the upgraded X-ray beam and the improved experiment station.

“It’s an exciting time for our beamline,” she said. “Brighter X-rays allow us to probe deep into materials with a higher-resolution beam and map very thin samples like these. At the same time, we have installed faster, more sensitive detectors to capture chemical or crystallographic changes occurring incredibly quickly. These two pieces come together to make world-changing projects such as this one possible.”

Uncovering materials that can withstand the conditions of hypersonic flight and are not prohibitively expensive to produce is key to unlocking their many applications.

The hypersonic materials project is supported by a $1.4 million contract from the U.S. Department of Defense Joint Hypersonics Transition Office through the University Consortium for Applied Hypersonics. The Embry-Riddle team’s principal investigator is William Engblom, professor of aerospace engineering, and Mark Ricklick, associate professor of aerospace engineering, is a co-principal investigator.

“Hypersonic vehicles experience excessive heat fluxes and skin friction, which tend to degrade surface materials, especially over long-duration exposure,” said Engblom. “Finding materials that can handle these conditions, and that are also easily manufactured and not cost-prohibitive, is needed to enable hypersonic vehicles.”

The materials could be used for military aircraft, weapons and interceptors, as well as civilian aircraft and cargo delivery vehicles that travel at hypersonic speed, which is generally considered to be at least five times the speed of sound. Comprehensive testing of such materials requires a wind tunnel capable of producing an airflow with the high temperatures and pressures consistent with hypersonic flight — and is therefore difficult and expensive to achieve. The device proposed by Embry‑Riddle would capture more detailed materials data in an intermediate, affordable test facility.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...