Driving EVs toward Lower Cost

The race is on to reduce battery and electric-drive systems costs while improving efficiency.

Market penetration of electric vehicles has been limited by two significant constraints: driving range and purchase cost. These two factors are in fundamental opposition, because the most costly part of a battery EV is its battery. Make that battery larger to increase driving range, as Tesla Motors has done with the Model S, and the result is a retail price in the six-figure range.

Reduce the battery’s size to hold down costs and the resulting driving range is unacceptably short. Indeed, despite progress on these issues, global EV sales will reach only 2.4% of all light-duty vehicle sales by 2023, predicts Scott Shephard, research analyst with Navigant Research.

The only way to overcome this situation is to drive down the cost of electric-drivetrain components. Major manufacturers are engaged on assaults on this paradigm, with new models such as the Chevrolet Bolt, expected to arrive as a 2017 model, coming to market amid claims of a 200-mi (322-km) driving range and a $30,000 price tag (after government incentives).

“Plug-in EV markets are expanding rapidly, and are set to grow much more quickly as several major automakers are slated to introduce vehicles in the high-volume SUV segment,” Shephard said.

Volkswagen CEO Martin Winterkorn told the German newspaper Bild that his company’s Silicon Valley Electronic Research Laboratory is developing a smaller, cheaper battery that will give one of its cars a 300-km (186-mi) range. “It will be a quantum leap for the electric car,” Winterkorn told the paper.

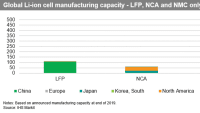

And Tesla is developing less-expensive vehicles than the Model S based on aggressive cost-reduction strategies. Its biggest bet is on its venture with Panasonic to build a Nevada “Gigafactory” which, Tesla forecasts, will produce more lithium-ion cells in 2020 than the entire world made in 2013.

Nissan apparently agrees with the value in having large, integrated facilities located in the U.S. as a cost-control measure for electric vehicles. The company builds Leaf EVs and their batteries in Smyrna, TN, as part of its cost-saving strategy, according to spokeswoman Paige Presley.

Battery-cell details

The Tesla Gigafactory’s gigantic scale and integrated on-site manufacturing will slice the cost per kilowatt-hour for lithium-ion cells by 30%, Tesla predicts. To aid with that cost-reduction effort, the company has signed researcher Jeff Dahn, a professor at Dalhousie University in Canada.

Dahn’s work has been supported by 3M since 1996, but the chance to work directly on products that will go to customers was appealing, he said. “I wanted to try in some small way to help the Gigafactory and Tesla succeed even more,” Dahn explained.

Today, Tesla sells its 10 kW·h Powerwall power backup and load-shifting battery array for $3500, revealing a price of $350 per kW·h. If the Gigafactory’s scale succeeds in reducing that cost by the 30% level claimed by Tesla, the price will be $245 per kW·h. But even that is not enough of a cost-down.

“Everybody wants it below $200, or even below $100 would be a good thing,” said Dahn.

So where is there room for improvement? It is in details, like the cost of the porous plastic separator membrane, he said. “The separator costs about $1.50 per square meter when you buy it in huge quantity,” Dahn reported. By comparison, a similar plastic film with no holes in it, costs about $0.06/m2 when sourced from the very cheapest Chinese suppliers, he pointed out.

“Somehow the process of putting holes in a separator raises the cost significantly,” he said. So Dahn aims to seek low-cost ways to produce plastic films for separators with 50% porosity at a cost closer to 6 cents per m2 than $1.50.

Similarly, there are costly metals in lithium-ion batteries, such as the nickel and cobalt used in battery cathodes (positive electrodes), he said. “The more nickel and cobalt you can replace with manganese, the better the cost will get.”

In contrast, however, there isn’t likely to be much opportunity for cost savings by refining the use of aluminum foil layers in the batteries. “We have a lot of experience making aluminum foil, so there is not much cost to come out of that,” he said.

But a less-obvious avenue for savings is through improvements in battery durability. “Another way to think of cost reduction is, if you increase the battery’s lifetime, you effectively reduced its cost. So that is one of the main areas we will focus on,” Dahn added.

Chevrolet’s dynamic duo

Chevrolet hasn’t yet released the technical details of the Bolt, so we don’t yet know how that car will achieve its ambitious targets. But the company has discussed the second-generation 2016 Volt, with its electric drivetrain.

The 2016 Volt’s LG Chem-supplied lithium-ion battery pack contains 192 battery cells instead of the outgoing model’s 288. So reducing the number of cells needed to do the job cuts the battery pack’s cost correspondingly, and it also trims 30 lb (about 14 kg) from the pack as well.

“It would have been easy for us to tweak our existing battery to provide nominally improved range, but that’s not what our customers want,” said Larry Nitz, Executive Director of GM Powertrain’s electrification engineering team. “So our team created a new battery system that will exceed the performance expectations of most of our owners.”

That improved driving range stretches to 50 mi (80 km), in comparison to the old car’s EPA rating of 38 mi (61 km) of electric-only driving range. The company also made improvements in the Volt’s electric motors. The

two-motor drive unit is 5% to 12% more efficient than the old car’s drive unit. Impressively, it also weighs 100 lb (45 kg) less. One of the motors uses no rare-earth metals, while the other one uses far less of those metals.

And smarter programming lets the two motors work together in more driving scenarios, enabling the 2016 Volt to accelerate 13% more quickly to 30 mph (2.6 s) and 7% more quickly to 60 mph (8.4 s). All of these improvements can be expected to contribute to the Bolt’s low-cost battery EV solution.

Hydrogen solution

Another solution is to eliminate the large battery pack entirely, replacing it with hydrogen tanks to power a fuel cell, as in the new Toyota Mirai that has entered low-volume production for 2016. Getting rid of batteries is the true solution to low-cost electric vehicles, insists Matt McClory, manager of the fuel cell group at the Toyota Technical Center.

As with batteries, there is constant progress in the improvement of fuel cells, but fuel cells’ improvement curve shows that they will be much more cost-effective for the foreseeable future, McClory said.

The latest advances in fuel cell production for the Mirai slashed the cost of its fuel cell to just 5% the cost of Toyota’s previous fuel cell vehicle, which was built using a production Highlander. That far less costly fuel cell is also half the size of its predecessor. The improvements came in areas like automation of the cell membrane handling and the cell stacking process in assembling the stack.

Fuel cells employ expensive platinum as a catalyst, but recent improvements have let Toyota cut the amount of that dramatically, according to McClory. In fact, the need for platinum in fuel cells should soon reach the level currently used in catalytic converters for emissions control in internal combustion vehicles. That means that global demand for platinum would not increase as fuel cells replace conventional cars, he pointed out.

And while fuel cells normally need a humidifier to keep their membrane moist, Toyota found a way to eliminate the added expense of that device, making Mirai the first production fuel cell vehicle without a humidifier, McClory reported.

Toyota, like all the companies working on fuel cells, has improved the fabrication techniques for making its carbon fiber hydrogen tanks, which also drives down cost. And because the Mirai is a smaller vehicle than the Highlander-based model, it needs only two of the 70-MPa (10,150 psi) tanks (instead of four on the Highlander) to provide satisfactory driving range.

In the Mirai’s electric drive system, Toyota’s cost-saving solution was to recycle as many components as possible from its high-volume hybrid models. That has meant using a voltage-boost converter to match the fuel cell’s relatively low voltage with the higher-voltage motors from the company’s production hybrids.

“That was still cheaper than developing a motor and inverter at the custom voltage of the fuel cell,” he explained. Which is key, when cost is one of the primary obstacles to wider EV acceptance.

Top Stories

INSIDERDefense

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

Road ReadyTransportation

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Power

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Connectivity

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Transportation

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Aerospace

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance