The Man From APPA-E

Advanced R&D programs directed by Dr. Chris Atkinson are building the energy-efficient mobility future.

Engineers and scientists working in mobility R&D have described Dr. Chris Atkinson as a guiding light in their efforts to make future vehicle propulsion technologies more efficient— and commercially viable. One long-time industry associate dubbed him “the ultimate project manager”—and who could disagree? As a Program Director of ARPA-E—the U.S. Dept. of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy—Dr. Atkinson oversees the funding and progress of 20 or more R&D projects. He leads a team of engineers and commercialization experts at ARPA-E, focusing on improving the energy efficiency of connected and automated vehicles, advanced combustion devices, and energy conversion and storage systems in the transportation space.

The building blocks of future batteries, power electronics, EV and PHEV charging, IC engines, and related systems in their nascent stages of development, can be seen on the agency’s website. A visit to arpa-e.energy.gov reveals an extensive roster of promising R&D projects and programs that the agency is shepherding, many still too early for significant private-sector investment. They include thermal recovery systems; battery chemistries; rare-earth-free electric machines; bio- and synthetic-fuels and advanced switching, among many other initiatives.

And the merging of on-board sensors, controls, and connected-car capabilities to optimize vehicle energy efficiency was pioneered by ARPA-E’s acclaimed NEXTCAR (NEXT-Generation Energy Technologies for Connected and Automated On-Road Vehicles) program.

First authorized as a DoE subagency in 2007, ARPA-E was to an extent modeled after the defense-focused DARPA, the wellspring of today’s autonomous-driving industry. Its directive is to empower America’s energy researchers with funding, technical assistance and market readiness. The agency has its own budget and program directors, authorized by Congress, whose mandates are straightforward: Reduce U.S. energy imports; reduce the emissions associated with energy generation, storage, transmission, distribution and end usage (including transportation); and improve U.S. competitiveness in these areas.

Since 2009 the agency has provided more than $2.3 billion in R&D funding for more than 850 energy technology projects across all sectors.

“Anything we can do to decrease energy consumption in transportation is a clear imperative for us, and for the emerging technologies in automotive,” Dr. Atkinson, an SAE Fellow, told Automotive Engineering. By “we” he means the OEMs, Tier 1s, universities, national labs and the research community that do the ARPA-E-funded R&D work. ARPA-E identifies areas of energy efficiency that need greater focus, provides external funding, and develops a program in that area. Often, the agency “gets people thinking in new ways about potentially old problems.”

Its congressional mandate gives ARPA-E the luxury of being able to “look broadly across the energy spectrum and have a fairly long-term horizon, one that is not necessarily restricted by a road map,” said Dr. Atkinson, whose successful five-year tenure as project manager ends this year. “I’m a term-limited federal employee,” he quipped.

Strong industry partnerships

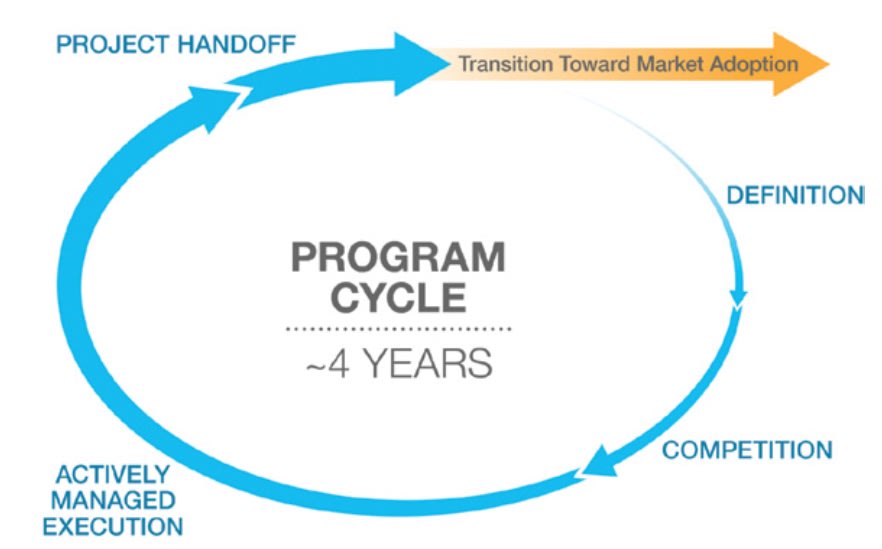

Research and development is the main focus, but everything ARPA-E supports “must have a pathway to commercialization”—a requirement Dr. Atkinson likes to emphasize. Any new technology must beat the incumbent in every performance metric including cost—“or it simply won’t gain traction in the commercial space,” he asserted.

ARPA-E insists that in order to secure funding, all the R&D teams that it engages should have at least a commercialization partner. “We’re not interested in this for the sake of science,” he stated. “We need to see these energy-efficiency improvements in commercial applications down the road. We understand that without a very solid OEM, Tier 1 supplier, or innovative-company partner, it’s much more difficult for our teams’ technologies to see the light of day. So, we’re very pragmatic in the ecosystem that we develop. It needs to have a very strong industry participation.”

The agency tracks the commercial impact of its advanced R&D

programs, including follow-on funding in the private sector, start-ups that are created, and subsequent inventions and patents. This year the agency reported 82 new companies had been formed from project work and 161 teams had raised a combined $3.2 billion in private-sector follow-on funding to continue moving their technology toward the market. And as of February 2020, ARPA-E projects had helped advance scientific understanding and technological innovation through 385 U.S. patents and 3,658 peer-reviewed journal articles.

“ARPA-E plays a critical role in sponsoring advanced technology that has the potential to be transformational, but requires further technical and market validation,” observed Fabien Redon, chief technical officer at Achates Power. He explained that support and guidance from ARPA-E staff “further enhances the value to the awardee and brings a valuable perspective to better leverage other ideas and understand the marketplace.”

According to Redon, the agency’s support was key to Achates demonstrating the potential of its OP (opposed-piston) compression-ignition engine to use gasoline and achieve class-leading efficiency in testing. In a follow-on project announced in 2019 and funded by ARPA-E, the company is partnering with Nissan Motor Co. and the University of Michigan to develop a hybridized OP engine for range-extender applications.

Despite the industry’s advances in electric propulsion, considerable R&D activity in advanced-ICE development continues with ARPA-E playing a significant role with well-known research partners such as Argonne National Laboratory, Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) and the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“To an extent we’re technology agnostic,” Dr. Atkinson said. “We’ve been pursuing a broad range of engine and powertrain architectures.” He sees promise in low-, zero-, or negative-net carbon fuels and in “divorcing the requirement to operate high-efficiency IC engines on fossil fuels alone.” ARPA-E funds external work on biofuels, for example. He’s optimistic that ICEs that deliver up to 60% brake thermal efficiency on low-carbon fuels have a future.

“We need a broad portfolio of high efficiency, low-impact propulsion technologies to meet our automotive transportation needs,” he said. “We see tremendous potential in having a very robust domestic biofuel or synthetic fuel industry. And that’s something to be applauded, as far as ARPA-E is concerned.”

He says the agency’s R&D teams are unique in their ability to take speculative steps, in parallel, for example in both engine architecture and in the application of new combustion regimes, to see what synergies may exist by marrying the two. ARPA-E supports such work, of varying duration, from concept through design, build, test, and development.

Pioneering the EV-AV fusion

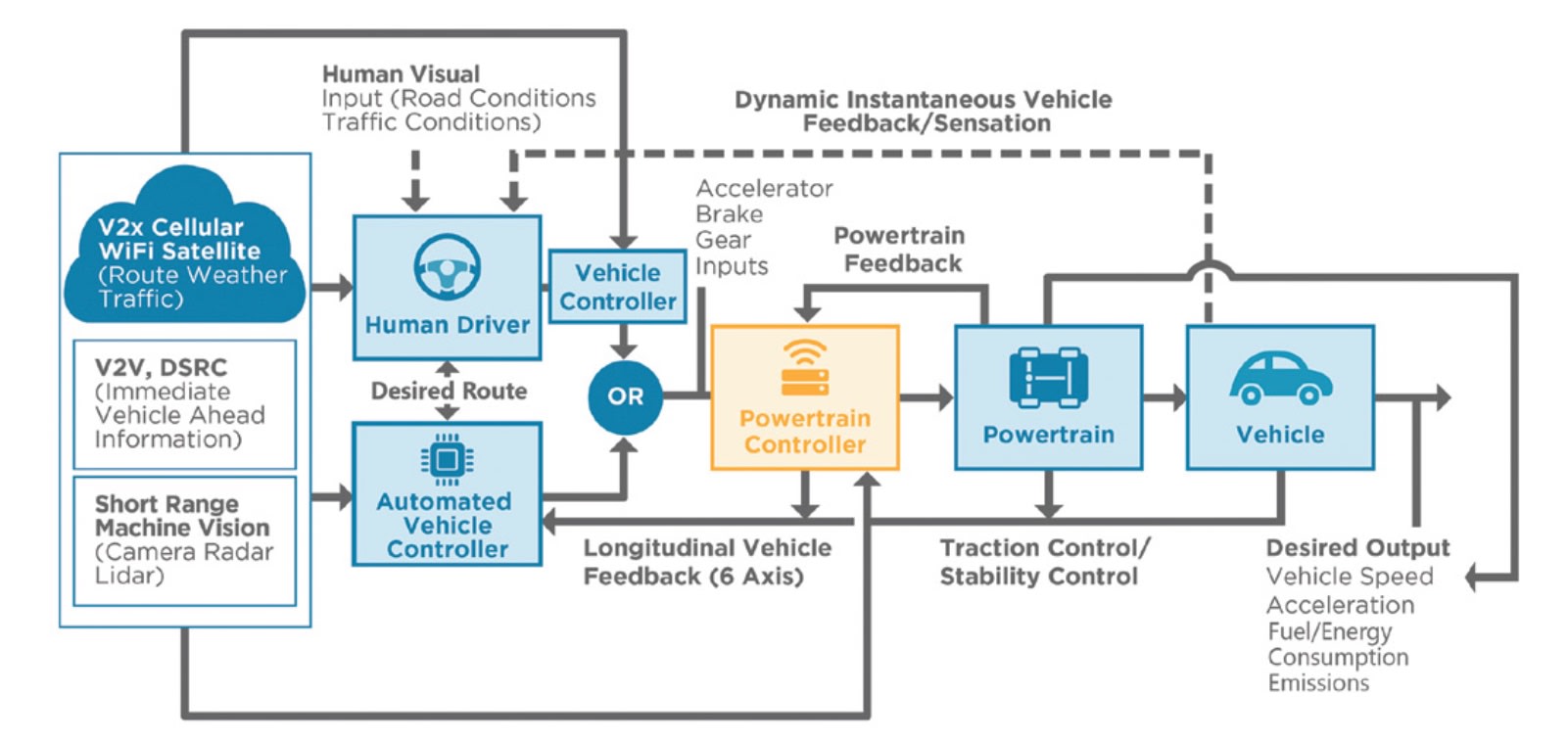

Merging the trends of vehicle energy efficiency with vehicle automation and connectivity—vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V), vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) and vehicle-to-everything (V2X)—is a point of APRA-E pride for Dr. Atkinson. “We’re not doing this merely for driver convenience or mobility as a service (MaaS), but for the good of driving down the energy consumption of future vehicles whatever their powertrain might be,” he explained. This was the genesis of the NEXTCAR program kicked off by Dr. Atkinson and his ARPA-E colleagues in 2016.

“People were looking at vehicle automation and new powertrain architectures and energy consumption in sort of an independent fashion, along two trajectories,” he observed. “NEXTCAR was the first program to really ‘fuse’ the two together in a convincing fashion.” Dr. Atkinson believes that the various NEXTCAR projects and their follow-on developments have the potential to achieve at least a 20% reduction in energy consumption for future CAVs (connected and automated vehicles).

The successful NEXTCAR program, currently nearing the end of its three-year funding term, has been by all accounts a model for industry and academia cross-collaboration. ARPA-E teams work with Toyota, Hyundai, General Motors—the GM group is a team unto itself—plus strong participation from Aptiv, Delphi, Bosch, Tula Technology and other suppliers. Also heavily involved are the engineering departments of seven universities.

“We set out to say it’s possible to achieve 20 percent additional energy efficiency improvement by harnessing the lower levels of vehicle automation, the SAE L1, L2 and L3, along with vehicle connectivity,” he said. “We’ve been able to show, for a wide range of vehicles and duty cycles and operating modes, a significant energy-efficiency improvement.”

The improvements, he explained, are greatest in the hybrids; less so with purely conventional vehicles, and less so with BEVs.

“What we’ve shown with hybrid-vehicle energy optimization is that any amount of ‘look-ahead’ information is valuable, whether it is about what the vehicle ahead of you is doing, or the traffic conditions up ahead, or the traffic signals ahead, or even the weather conditions. The more information you have, the better,” Dr. Atkinson reported. The industry’s progress in vehicle “eco-routing” (selecting a route not only based on speed, time and distance, but of speed, time, distance and energy consumption) as well as on-board capability to precisely signalize intersections, harmonize speed with heavy traffic, and employ predictive adaptive cruise control, all rely on look-ahead data and connectivity available with SAE L1-3 automation.

Further significant opportunity exists in the application of several NEXTCAR technologies to SAE L5 vehicles, as well as to increase the usable driving range of BEVs, he believes. Increasing levels of automation that ultimately take the driver out of the loop will offer not just safety enhancements, but also critical energy savings.

“The introduction of fully automated vehicles in the future will be a boon for energy efficiency and safety enhancements,” Dr. Atkinson stressed. “Connectivity and automation help increase vehicle efficiency. It’s a very compelling argument. The interesting thing about NEXTCAR is that the market and industry have moved so swiftly since we created the program. What we thought was several years away from commercial implementation is much closer. The earth has moved underneath us and has accelerated the rate at which these technologies can be integrated. That’s very encouraging.”

He closed the conversation by noting that 22% of the energy consumed in the U.S. is for road transportation—and of that, currently 58% is consumed by light-duty vehicles—about 13% of all energy consumed.

“If then we can improve the energy efficiency of all vehicles by 20 percent, that’s more than 3 percent of all energy consumed in the U.S.. That’s an enormous potential improvement,” Dr. Atkinson said. “So, we’re moving more swiftly to a merge point. Of course, all this good work will be undone if the total number of vehicle miles traveled by the fleet increases at a greater rate.

“And that makes improving the energy efficiency of each and every vehicle an imperative,” he asserted.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...