Converting Classic Cars Is Just Step One of This Mission

Electrogenic has developed EV conversion kits for seven models that are of interest to classic vehicle collectors. But it’s a smaller, lower-cost version for Africa that might offer the real solution.

Electrogenic founder and CEO Steve Drummond believes EVs are here to help. “Saving the World One Car at a Time” is even painted on the company’s headquarters near Oxford, England.

The original business plan was to develop electric powertrains for smaller automakers that couldn’t shoulder the expense of in-house development. That’s still a big part of Electrogenic, which also does EV conversions for Britain’s military.

But just as Electrogenic got rolling, COVID-19 hit, and lockdowns in England and elsewhere slowed business. “We needed to broaden our customer base and decided to expand into EV conversions for car collectors,” Drummond, a mechanical engineer who started his career in the nuclear power industry, told SAE Media.

Growing industry

There are countless relatively wealthy car collectors around the globe, some with a growing awareness of the benefits of vehicle electrification, not only environmental but also performance, reliability and low operating costs. A big issue in the community, Drummond said, is that as cherished vehicles age, it becomes more difficult to find parts and professionals who can keep gears turning and pistons pounding. Some collectors, he figured, would look at electrification as a way to keep a favored vintage car on the road. He’s not the only one. A 2024 report from Industry ARC estimated that the sale of EV conversion powertrains will be a $2 billion market by 2030.

A drop-in kit

There are other companies, like ECD Automotive Design and Charge Car, across Europe and in the U.S. that provide EV conversions for classic cars, typically one-offs and often with used motors and batteries salvaged from wrecked Teslas and other major brand EVs. Many require chassis and electrical modifications and don’t supply all the bits and pieces necessary to make them. Electrogenic’s twist was to develop a complete conversion kit, using all new components, that could be easily shipped anywhere in the world and installed in a relatively short period by a competent mechanic.

European regulations require expensive testing and mountains of paperwork if anything structural on a car is altered, so Electrogenic engineers its kits to be true drop-ins. They use the original engine and transmission mounting points to install the electric powertrain into the vehicle without any metal bending, welding or a single hole to be drilled.

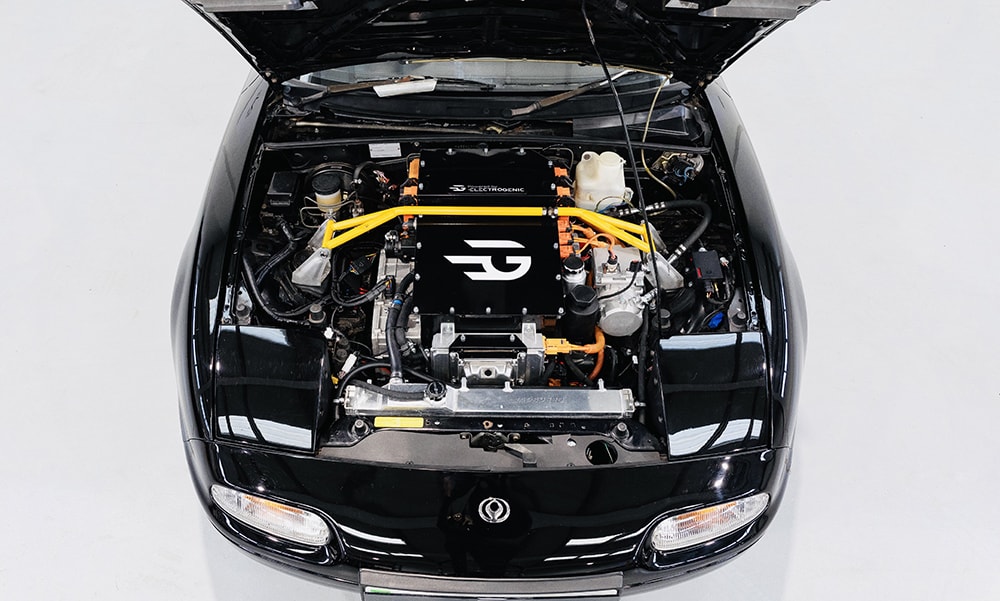

The kits are built around new motors, batteries and CCS charging equipment sourced from outside suppliers. The gearboxes, battery enclosures and battery, operating and control software and many of the electronics are done in-house.

An Electrogenic dashboard control unit (DCU) enables compatibility with the vehicle’s instrument panel, translating digital signals from thwill display on the gauges of a 30- or 40-year-old car.

Many of the components are the same from kit to kit – there are currently seven kits, with several under development – but each kit is tuned for a specific model, and, within model lines, even for specific purposes such as cruising or performance driving.

So far, Electrogenic has released conversion kits for 1948-1985 Series Land Rovers, 1983-2016 Land Rover Defenders, E-Type Jaguars (XKEs in the U.S.), 1974-1994 Porsche 911s, the DeLorean DMC-12, the “classic” Mini built from 1959 to 2000, and the first-generation 1989-1997 Mazda MX-5 Miata. The company also offers a pared-down “agricultural” kit for Defenders used primarily as farm vehicles.

‘It’s all there’

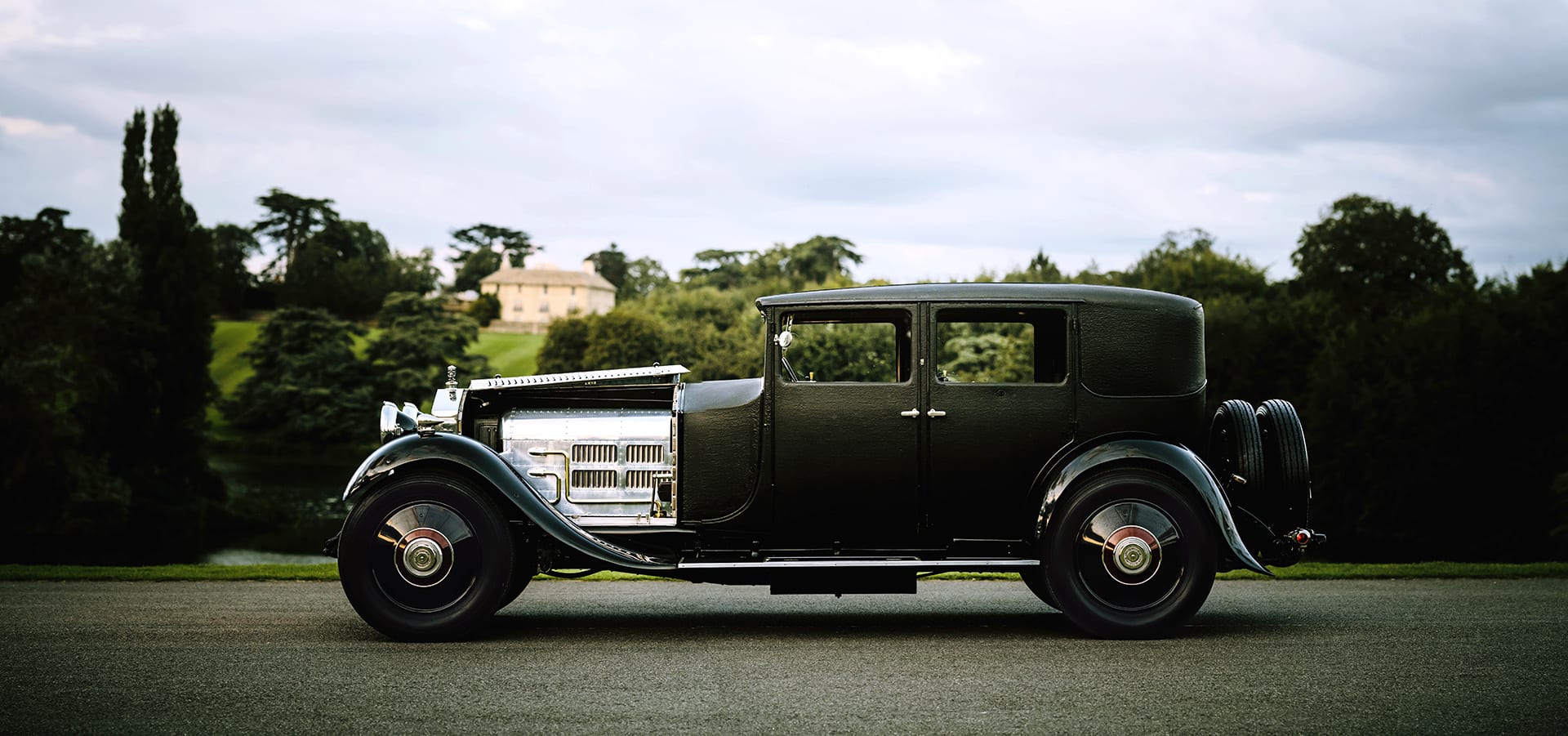

The company will do one-off conversions for customers who want to spend the cash – its most famous electrification was converting a 1929 Rolls-Royce Phantom II for actor Jason Momoa. The newly electric Rolls debuted in 2023 after an 18-month project that Drummond calls “enormously technically challenging.” But the main focus is the development of conversion kits that enable its EV system to be taken to the customer rather than requiring customers, many from the U.S., to ship their cars to England. Installers – there are 13 now, including four in the U.S, one on Canada’s west coast, five in the U.K. and one each in Australia, France and the Netherlands – seem to love the concept.

“It’s all there. I don’t have to go running around looking for things to make it fit or to finish the job, and if I have an issue, I just call them in England, and they take care of it. That’s important,” Shinoo Mapleton, a Lotus performance specialist and race car designer, told SAE Media.

Mapelton found that out first-hand when his Southern California operation, InoKinetic, started its first Electrogenic kit installation on a classic Jaguar KE in 2023. While the vendor for Electrogenic’s battery charging systems assured the company they’d work both in Europe and the U.S., CCS fast-charge protocol differs on either side of the Atlantic, and the systems supplied with the first Jaguar E-Type kits didn’t work in North America.

Mapleton said it took almost a year to get the charging system revamped and that Electrogenic handled it all the way, sending engineers to the U.S. multiple times to check on vehicles at its various installer partners ’shops.

How it’s done

Electrogenic kit development typically starts with a bespoke conversion. If Drummond and his team decide there’s a market beyond that particular collector, the work begins. It takes about 500 hours – spread over six months or more – to develop a kit, Drummond said. The first step is to sample internal combustion versions of the target vehicle in order to get a good idea of that model’s driving characteristics, including any differences between left- and right-hand drive versions.

One of Electrogenic’s hallmarks is that its kits don’t negatively impact the way the original car handles. We had the opportunity to take a recently electrified 1974 Jaguar XKE for a test drive and found it to be slightly more responsive and agile – and much quieter – than internal combustion XKEs of the same era.

The Electrogenic kit reduces horsepower by 50% from the 245 hp promised by the Jaguar’s V12 engine when new, but it boosts torque to 475 lb-ft (644 Nm) from the gas engine’s 285 lb-ft (386 Nm) for a much snappier launch, especially in sport mode. The kit also provides eco and normal modes, for less throttle response and greater regenerative braking levels. The conversion also lightens the front end and improves front-rear weight balance for improved handling.

“You want to bring out the best characteristics [with the conversion] and try to fix the worst ones,” Drummond said.

It took nearly two-and-a-half years of trial-and-error to perfect a gear reduction box for the XKE kit that was both quiet and able to handle the electric motor’s 15,000 rpm, he said. The original V12 engine lumbered along in the 5,000-6,000 rpm range.

Electrogenic engineers also had to develop a special cradle for the front battery box that would bolt onto the Jag’s space frame using the existing motor mounts. The box not only holds the battery cells but also serves as the mounting point for the vacuum pump and helps stiffen the front end.

The first step in kit development is to scan the drivetrain under various loads, followed by a digital scan of the engine bay, transmission tunnel and fuel tank areas. This provides Electrogenic’s technicians the measurements needed to design the battery boxes, determine the proper motor and gear-reduction transmission, design the mounting hardware, wiring, and battery cooling system plumbing, and determine how to route it all through the car without cutting or drilling. A computer simulation is developed for that model, which is then run to see if any additional alterations are necessary. Finally, everything is installed and final tweaks are made.

One version of the XKE kit uses an auxiliary battery mounted in the fuel tank void in the trunk area. Routing the thick high-voltage cables through the vehicle without impacting its structure was a considerable challenge, Drumond said.

Electrogenic’s technicians write proprietary software that controls the powertrain and enables the link-up between the high-voltage EV system and the car’s 12-volt components, such as climate control and audio systems, dashboard instrumentation and lighting.

Once all that’s done, the kit is tested on the road “for many, many miles,” Drummond said. If both right and left-hand drive versions of the vehicle were built, it is tested in both.

In a kit developed for the MX-5 Miata, the electric motor and single-speed gear reduction transmission required a shorter torque stiffener than the stock piece that runs from the transmission tunnel to the rear axle, so Electrogenic designed one that bolts in. Because the Miata is so small, Electrogenic engineers also had to develop a shorter EV transmission than they use in other kits.

Development of a kit for the Citroen DS ran into trouble because the car’s inboard brakes are mounted to the gearbox, which normally would have been removed and replaced with one from Electrogenic. Instead, the company designed a single-speed transmission to fit inside the original Citroen housing.

All of the kits are engineered so that none of the vehicle’s original parts need to be destroyed. Some, including analog gauges, are repurposed for EV use. The Miata kit even eschews the rotary shifter used in other Electrogenic kits and retains the car’s stubby “stick” shifter, although it only moves in a straight line between Drive, Park and Reverse.

“The original engine, transmission, and anything else that’s removed can be stored, and the electric conversion can be totally reversed if an owner wants to do that in the future,” Mapleton said. His company has done three Electrogenic conversions so far, two XKEs and a Land Rover Defender – and has a fourth in the queue: a stainless-steel-bodied DeLorean of the type made famous by“ Back to the Future.”

Conversions, even with a prefab kit, can be expensive, though.

“A substantial investment for something you don’t need,” car collector Chris Clough said of the $110,000 he paid for an Electrogenic conversion kit and installation to turn his 1995 Land Rover Defender electric.

Clough went electric with the latest addition to his collection because he wanted to turn the Defender into a daily driver that was reliable, quiet and easy to drive. He also wanted the torque an EV provides, to smooth out the hills around his home in the Lehigh Valley north of Philadelphia.

Electrogenic kits don’t include restorations. The company’s installer partners must ensure that a customer’s vehicle is structurally sound and fix any problems before the conversion.

Clough said he bought the Defender from a high-end restoration company for $250,000 before launching the electrification project.

Another EV converter, Everatti, does bespoke EV conversions that include full luxury restorations, at prices – vehicle not included - that begin at around $250,000 for a vintage Defender and can start at close to $500,000 for a classic Porsche 911.

“Many [conversions] aren’t value propositions,” said Andrew Whittam, a former British Airways B-777 pilot and aircraft engineer. Whittam’s New Jersey-based Whittam Engineering did Clough’s conversion and has seven Electrogenic EV conversions, mostly Defenders and XKEs, under its belt so far.

Is Change Coming?

Electrogenic might be on the road to revolution, though – both in price and in the kinds of cars that are candidates for an EV conversion. Its Miata kit is for an “everyman” sports car. While kit and installation today is around $50,000, decent early Miatas can be picked up for under $20,000 – and a lot less if the engine or transmission is blown. That can make for a package that’s affordable for many, especially those who already own the car.

And the company is about to release a do-it-yourself kit for the classic Mini, priced at about $29,000 U.S. An auxiliary battery that nearly doubles its range, to 150 miles from 80 (to 241 from 129 km), is an additional $9,000.The kit is assembled and shipped on a bolt-in subframe and can be installed by a reasonably skilled home mechanic. All of the equipment is tested and validated at Electrogenic, which means no dangerous high-voltage wiring for installers or customers to deal with. Mapleton told SAE Media that, based on conversations with Drummond, he susects the system might be a forerunner for an even smaller, easier-to-install and cheaper system aimed at the African market.

Drummond declined to talk specifics but would say that he sees the African market as ripe for electrification, given the unreliability of older cars that are driven for decades and the difficulty of obtaining parts and even fuel in many areas of the continent.

“There is a lot to do there and petrol and diesel are not good solutions for most of it,” Drummond said. “The Mini kit is built around a motor that would be great for local delivery vehicles in Africa, but the key to Africa taking up EVs convincingly is local manufacture in Africa for Africans.” Electrogenic, he said, “may well have some ideas around that.”

Top Stories

NewsRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsPower

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

ArticlesAR/AI

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Automotive

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Automotive

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Energy

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance