Replicating the Racing Experience

Professional driving simulators can be successfully exploited to shorten the traditional design-prototype testing-production process relative to a new racecar.

Vehicle dynamic simulation is a mature engineering process thanks to professional driving simulators. Vehicle dynamics studies have been repeatedly tackling the conflict between detailed simulation models and the need for real driver feedback. The solution to this conflict has been devised through the use of professional driving simulators, capable of representing the surrounding virtual environment with high accuracy. Simulators eliminate the need for driver models by including the real driver in the simulation loop: the driver himself runs the simulations, receives realistic feedback, and generates track data for engineers of all departments.

This approach has been applied to the concept and early development of the Dallara 2014 Super Formula (SF) racecar, which debuted in the Japanese SF series in 2014. An identical simulator was also installed in April 2014 at Dallara IndyCar Factory near Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

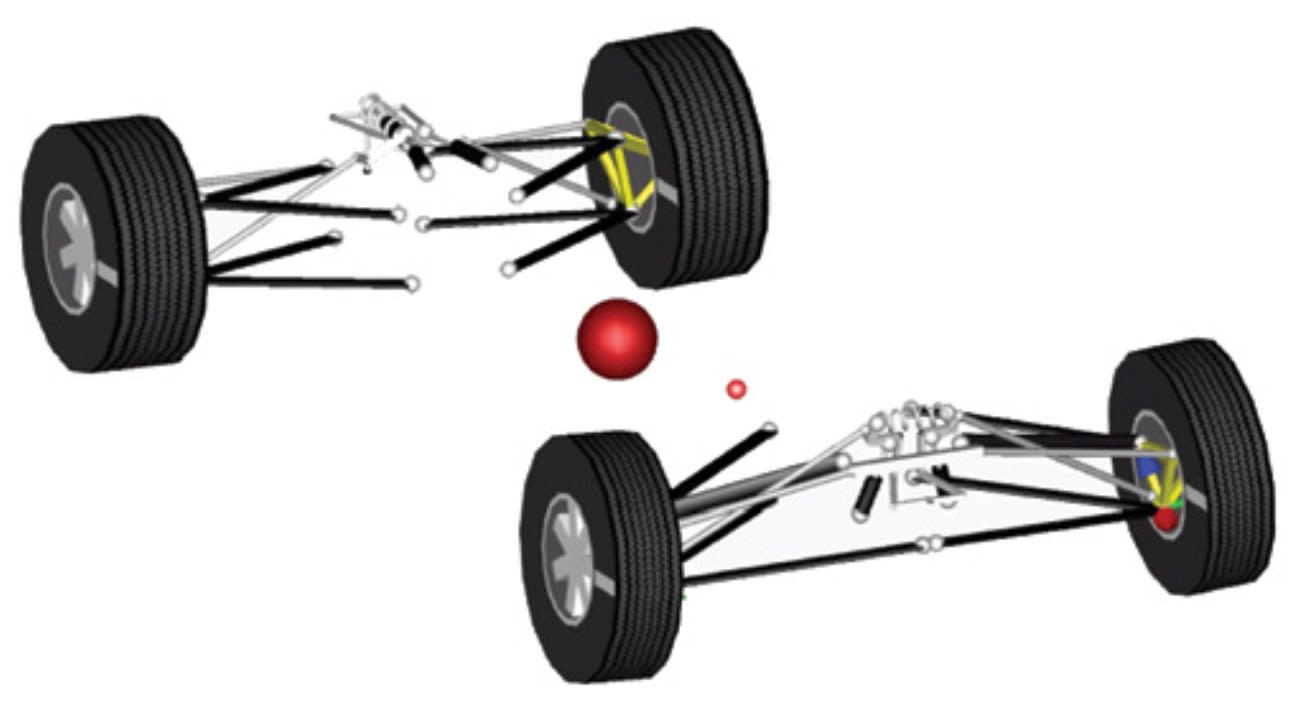

Well in advance of manufacturing the prototype and even before starting the design, regular race drivers, chosen by both of the engine manufacturers involved in the SF series, have been testing various “virtual” cars in terms of suspension, aerodynamics, steering geometry, weight distribution, track width, and wheelbase, all with the simulator. These same drivers have helped engineers from all areas finalize the design requirements to meet the necessary handling performance and contributed to achieving the target feeling, with the benefit of an overall reduction in time and cost.

An authentic experience

Advanced and professional driving simulators truly capable of convincing drivers that they are piloting a real car, by necessity, feature an environment where every detail reproduces reality with the greatest possible fidelity. No compromises can be accepted for any aspect, from graphics to car handling and track surface profile to replication of vestibular (spatial orientation) and proprioceptor (body position, motion, and equilibrium) stimuli, as perceived when driving the real car.

In the past five years, driving simulator technology has consolidated certain features as mandatory choices to achieve this performance: less than 1 ms real-time simulation clock time, laser-scan quality track geometry description, detailed graphics complete with dynamic effects, outstanding motion platform movement in terms of dynamic response, and 1.524 m (5 ft) or more actuator stroke. All these features need to be managed in real time by detailed vehicle models, able to include various nonlinearities, compliances, and high-frequency features that dominate the transient behavior of the real car.

All these aspects define the difference between commercial simulators, whose fundamental scope is to help drivers learn new tracks or train young drivers, and professional simulators, which support the engineering decisions at a very early stage with a high level of confidence in the final results.

Early concept evaluation, design decisions, track data generation for suppliers, and setup development for race engineers well before arriving on track, are a few clear advantages of using a professional simulator.

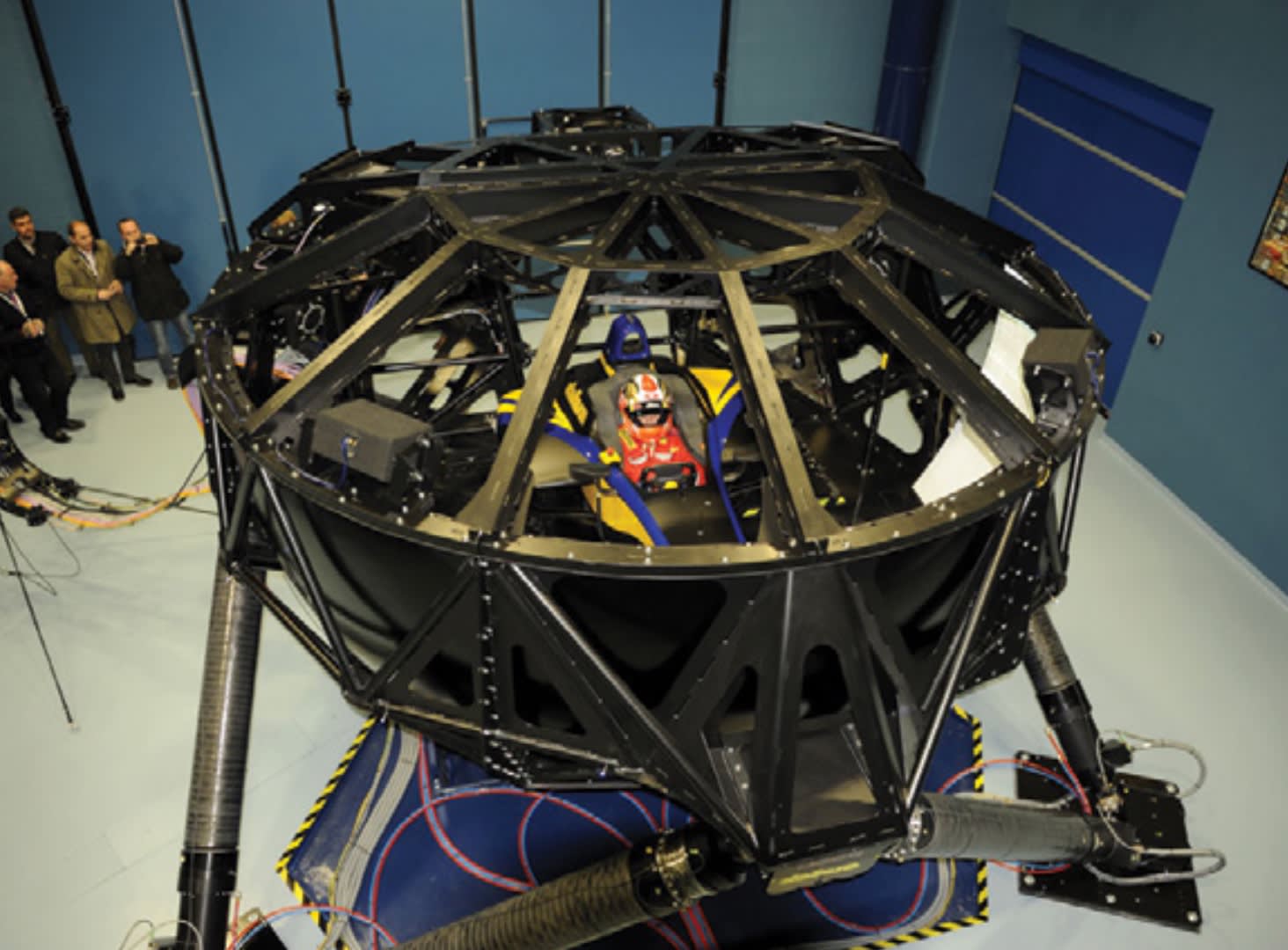

A few professional simulators are available from chassis manufacturers and independent companies. They are generally based on a Stewart hexapod layout.

In one example, a hexapod supports a 4-m (13-ft) diameter cage. The platform accommodates a single, 180° field-of-view screen and three QXGA projectors able to reproduce the visual environment. Either a single-seat chassis or road car frame can be installed inside the platform to accommodate the driver, seat, and all controls. Six independent actuators generate a motion envelope of 8 × 8 × 6 m (26 x 26 x 20 ft). The design of the cage is customized to feature low weight and high stiffness, such that the moving platform is capable of generating more than 2 g linear accelerations in all directions, 2-m/s maximum linear velocity, and a first structural resonance frequency above 40 Hz.

The consequence of this high dynamic response is the ability to provide the driver with the appropriate amount of stimuli necessary to feel the car’s transient behavior while driving over road irregularities.

The high-fidelity motion platform, combined with an efficient real-time computation and a detailed vehicle model, can manage the simulation when combined with a very small output time-step (typically 1 ms or less), the real-time driver controls, and the laser scan quality road profile.

The main technical challenges imposed by the performance required from the simulator include:

- Platform design: Minimize mass to achieve the maximum thrust force from the actuators; maximum stiffness-to-mass ratio to increase the first resonance frequency of the platform well above the typical wheel hop frequency of ground effect racecars. Consequently, patented technologies had to be developed to improve/modify/replace commercially available components, otherwise inadequate for this application.

- Projection system and graphics software: Onboard projectors are subject to vibrations and dynamic deformations that are perceived by the driver in terms of poor synchronization between the movements of the platform and the generated on-screen image. Additionally, professional drivers are extremely sensitive to the detailed environment (trees, braking boards, curbs), the ambient lights (depending on the time of day), and the dynamic shadows as the car goes beside large graphical objects such as grandstands and control towers.

- Track profile: High-quality track data is needed to represent all the small irregularities such as bumps and junctions which, at high speed, significantly influence the handling of the car. It is therefore necessary to utilize track profile data acquired via laser-scan technology: the challenge here is to manage a quantity of data so vast that it cannot be stored in the volatile memory of the system.

- Vehicle model: The vehicle model has to fully represent all the details, including nonlinearities such as tires, dampers, aero-dynamics, engine curve, steering and suspension kinematics, and compliances, and still be fast enough to interact in real time with the driver controls, the platform movement, the track profile, and the graphics in a way that it is fully transparent to the perception of the driver.

The above challenges necessitated the development of in-house, fully multibody customized vehicle models, able to describe the real car and represent different physical phenomena (such as the thermo-mechanical performance of the tires, the hydraulic characteristics of the dampers) as required by customers or permitted by regulations.

The model is crafted with the open-source Modelica language along with the associated Dymola customizations, developed by Dassault Systèmes. The vehicle model has been conceived to be modular, allowing engineers to replace, modify, add, and refine system “blocks” such as tires, aerodynamics, engine, suspension, driveline, or link external blocks (e.g. from MathWorks’ Matlab).

The SF racecar

The SF car features a 550-hp (410-kW), four-cylinder, inline, turbo engine, capable of achieving more than 4 g lateral acceleration while cornering and 1650 kg (3600 lb) of total downforce at 300 km/h (186 mph). Two prototypes were tested in July 2013 at the Suzuka race track.

The remarkable characteristic of the SF project, specifically for the vehicle dynamics engineers, has been the adoption of a professional driving simulator during the very early stages, which led to an innovative experimental-through-simulation approach to find answers to recurring engineering questions.

Well in advance of component design and production, driving sessions were conducted with regular racecar drivers and their race engineers to evaluate key design parameters and determine the most effective solutions.

Areas investigated with the simulator included lap-time prediction, suspension components’ load generation, aerodynamic layouts, and power steering assistance.

Most notably, the simulator was essential in the early design of the power steering system. The simulator is seen as an accurate and repeatable generator of data for the power steering system supplier: drivers have been running sessions in the simulator to evaluate different steering geometry layouts and levels of assistance.

Historically, only Formula One, among all open-wheel racecars, has ever included a power steering unit because of the weight and the cost of the system coupled to the cornering performance and duration of the races. Based on the above considerations and the steering latency and compliance perceived by the race driver with a power steering system, the initial concept of the SF car did not account for such a technology.

Correlation, or at the very least, extrapolation between the previous-generation car and the new car was not possible due to the engine (aspirated vs. turbo), tires, overall weight, and safety requirements, which were constraining factors in the packaging of the steering system, in addition to the large differences in aerodynamic performance.

On the simulator, the drivers who would eventually drive the real car, gave clear feedback that some steering assistance was required. Their suggestions gained further strength from the ability to reproduce entire races on the simulator, complete with pit stops for tires and fuel, while observing the ability of drivers to keep a consistent race pace without committing major mistakes. The typical race length required by the organizers, the high average speed of Japanese tracks, the typical body characteristics of many Japanese drivers would have stressed the drivers too much, to the detriment of the race itself. Overall, it was necessary to tailor the power steering assistance such that it was at a level high enough to cope with the contest (race length, drivers, performance) and low enough to make the car challenging.

The simulator was an invaluable tool for designers during the very early stages, in particular when identifying the right range of power assistance, selecting the appropriate electrical motors, defining the requirements for the loom layout, the current draw, and the size of the alternator. A higher level of assistance would have resulted in extra weight and cost; a lower assistance would have required an expensive redesign to accommodate a larger unit into a fully designed monocoque.

An invaluable tool

The development of the SF took place in Dec 2012 and helped engineers commit to a robust concept of the car at a very early stage of the design process. Their decisions, as hazardous as they would appear due to tight time limitations, have been validated through numerous track sessions between July and September 2013. With the design confirmed at the track, the manufacturing of the production car was given the green light in September 2013.

Professional drivers are needed at a very early stage of the process. This is key for driver-in-the-loop professional simulators.

The advantage of using a professional driving simulator as an early and robust racecar development tool is self-evident when considering the aforementioned examples of reduced development time and associated costs. Engineers from all departments are also required to cover aspects from transmission, engine ECU, aerodynamics, steering, suspension loads, dampers, critical component design for fatigue, and ultimate strength.

The process of developing the SF car can be applied to the development of any racecar or road car. Other applications that would benefit from the work on a simulator might include the design of new race tracks before starting the construction work, the assessment of would-be professional drivers, the design of advanced hardware components, and the development of traction control software and engine control unit management.

This article is based on SAE International technical paper 2014-01-0099 by Alessandro Moroni, Dallara Simulator Manager, and Andrea Toso, Dallara Head of R&D.

Transcript

No transcript is available for this video.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...