Composites Permeate Inside and Out

Composite materials are gaining popularity for both unseen structural components and for exterior eye candy.

According to Lux Research, automotive use of carbon-fiber-reinforced plastics will swell to $6 billion by 2020, making the segment larger than the aerospace industry’s use of carbon fiber despite the lower cost of automotive-grade parts.

“The onset of mainstream adoption in automotive will drive volumes that will dwarf other industries, but companies wanting a piece of that action will need to be positioned before the inflection point in the market, or pay a massive premium to buy in late,” warns the Lux report.

With this in mind, carbon fiber supplier Toray Industries’ Zoltek subsidiary plans to double the production capacity of its Jalisco, Mexico, plant to 5000 ton (4535 t) per year, staring in April 2016. Jalisco and a plant in Hungary produce large tow fibers, for which increasing demand for automotive structures will result in a shortage of production capacity by early 2016, the company says. Large tow fiber has 40,000 or more filaments and is suitable for the kind of reinforced plastic components commonly used in cars.

In response, Zoltek says it plans to double its current total production of 13,000 ton (11,800 t) of large tow fibers per year by 2020. Indeed, the Frankfurt Motor Show saw use of carbon-fiber materials accelerate into new applications, such as the structural reinforcement of the new BMW 7 Series’ steel unibody, which the company has branded “Carbon Core.”

BMW uses carbon fiber from its subsidiary SGL Group. “The use of our carbon fiber-based products in the new BMW 7 Series is another milestone in the large-scale serial application of carbon materials in the automotive industry,” said Jürgen Köhler, SGL Group CEO.

Köhler also agrees with Lux Research’s view of the value of getting a head start in this market. “This project also further underlines the great potential of carbon fibers for innovative automobile applications and demonstrates that SGL Group’s long-term development of the entire value chain is paying off,” he said.

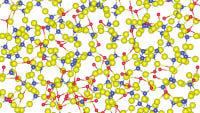

Chopped fiber flexibility

Another application in the spotlight in Frankfurt was Lamborghini’s use of forged-composite components for the Aventador Super Veloce Roadster. Maurizio Reggiani, Lamborghini’s Director of Research and Development, pointed to forged-composite carbon-fiber components on the car such as its instrument panel surround as an example of an emerging technology.

Benefits of forged composites, which use chopped carbon fibers rather than pre-impregnated fabric sheets, are cost and its easy formability into shapes, he said. “This is a low-pressure vacuum process instead of high pressure,” Reggiani explained.

The resulting product is heavy and not as strong as conventional carbon fiber, in exchange for its lower cost and greater flexibility. But that doesn’t mean that it is worse, only different, Reggiani insists. “In some cases, there are advantages,” he said. For example, the random distribution of fibers produces unique, one-of-a-kind appearance for every part. “The appearance is really cool in some cases.”

There is also the matter of tolerance of drilled holes for mounting components. A drilled hole cuts the strands in conventional carbon fiber, weakening it. That isn’t a problem with the short chopped fibers of forced composites, Reggiani pointed out.

As Lamborghini gains experience with forged composite technology, it is able to reduce its weight penalty compared to conventional carbon fiber, he added. “It can be really close to the same weight with really good engineering.”

Why go to the effort? Because the production time is so much shorter for forged composites, he said: “If you produce a monocoque in 100 hours, for example, it takes eight hours in forged composite.”

Conventional success

Costs in conventional carbon fiber are falling, though. While it was once about $50 per pound, today the Toho Tenax carbon fiber used by Chrysler supplier Plasan Composites is down to about $8 a pound, reports Mike Shinedling, Viper program manager at Fiat Chrysler Automobiles.

Over time, the Viper has evolved from zero carbon fiber to mostly carbon-fiber bodywork, he explained. The car gained an available carbon-fiber wing in its second generation, then added some carbon reinforcements in the door frame and A-pillar area for the third generation. By the fifth generation, most of the exterior bodywork was carbon fiber, and this evolution has produced a car that is now lighter than those very first Vipers were.

“Any other car that has existed in that same time frame, the weight has gone up,” Shinedling proudly points out. Between 100 and 120 lb (45 and 55 kg) of weight loss is attributable to using carbon fiber, he said.

While the carbon bodywork has helped whittle away weight, its strength was needed for applications like the rear wing and front splitter, which apply significant force to the car at speed.

Shinedling appreciates the appeal of processes with faster cycle times than the time-consuming autoclave process of prepreg carbon fiber. But the cost of tooling for those alternatives doesn’t make sense for a low-volume vehicle like the Viper.

“We did look at faster cycle time processes, but it was a financial equation of the tooling cost versus the piece cost,” he said.

But future programs may call for that, and the Viper team’s experience with the material will be critical for Chrysler as it considers those possibilities, according to Shinedling.

“It has been a good test bed and training ground for us to expand carbon fiber to other vehicles when the time is right,” he said. “I think having a vehicle like the Viper allows us to have a core team that is well prepared to execute on other projects that are maybe even medium-volume production.”

Composite sandwich

The experts at Covestro (formerly Bayer MaterialScience) point out that there is plenty of weight to be saved inside cars, using materials like its Baypreg, which is a composite honeycomb sandwiched by fiberglass mats that can be used for parts such as sun shades and rear cargo load floors.

“One of the primary things that is on [OEM customers’] minds is weight,” noted Nate Goshen, Industrial Marketing Manager for Covestro. “When you can save them 30-50% weight on a part, that gets their attention.”

Additionally, handles and other attachments can be molded into the composite, saving on the number of parts and the labor to assemble them.

“You get a stiff, lightweight part that meets the requirements,” Goshen explained.

Because Baypreg has many variables — the thickness of the honeycomb, the chemistry of the resin, and the weight of the fiberglass “bread” layers in the sandwich — it can be adjusted to meet varying requirements for thickness, weight, and strength.

“You can really tune this chemistry,” said Goshen. Further, because it is thermoset, Baypreg isn’t susceptible to heat-related degradation in service, he added.

With composites steadily encroaching on car construction from both inside and out, it is easy to see why market forecasts are bullish.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...