The Battery Man Speaks

The speed of progress in automotive lithium batteries has impressed AABC’s Dr. Menahem Anderman. So has silicon-graphite anode technology development from Tesla and Panasonic.

The future of vehicle electrification is all about the battery. The industry’s steady progress in reducing lithium-ion battery cost while increasing energy density, durability and reliability has surprised one of its leading experts, who is quick to admit a miscalculation he made six years ago.

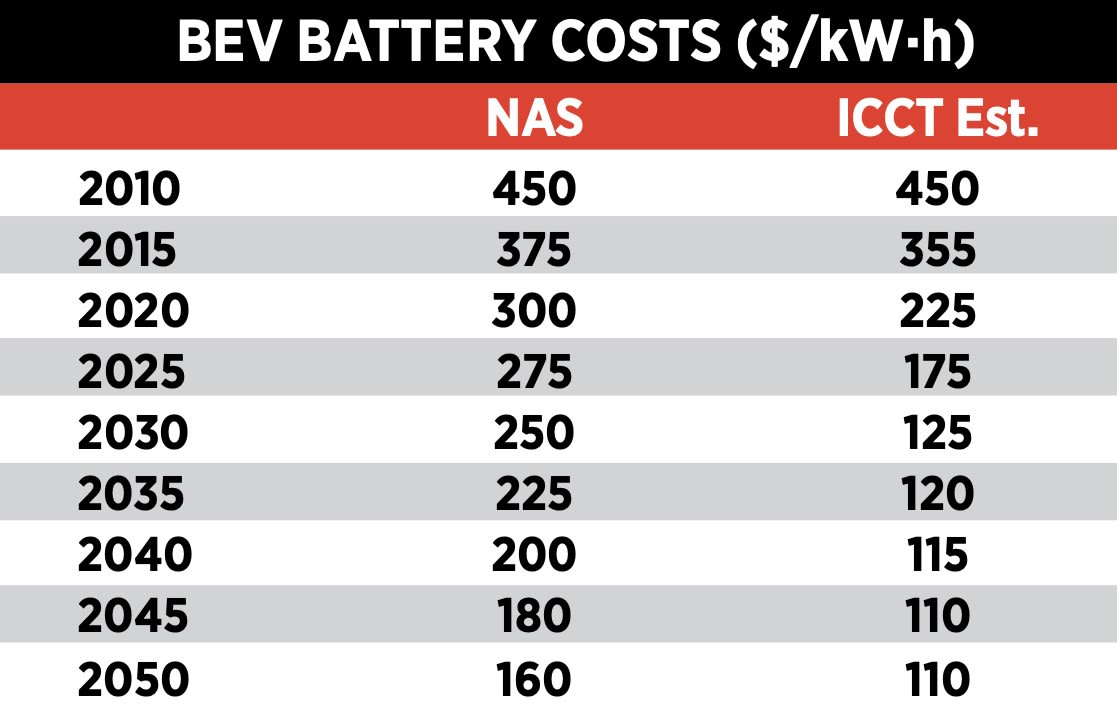

“Battery costs are coming down faster than I predicted — and faster than the major Japanese cell producers who have been my clients for many years predicted,” said Dr. Menahem Anderman, independent battery-industry consultant, founder of the well-known Advanced Automotive Battery Conference (AABC) series and frequent speaker at SAE’s Hybrid & Electric Vehicle Symposia.

In 2010, Dr. Anderman completed a milestone study on battery cost in which he interviewed top cell and material suppliers and vehicle OEMs. “They believed then that it would take 10 years to reduce costs to $300/kW•h. Well, that’s already happened,” he asserted in an interview with Automotive Engineering.

Significant work is still ahead, he cautioned, in order to reach the $150-$100/kW•h threshold that will finally put EVs on a cost par with IC engine vehicles, “tipping the scales” to widespread electric mobility. And while energy density is improving, “maintaining safety is really the biggest barrier to improved performance,” Dr. Anderman explained.

Plug-in hybrids, he observed, were almost anathema to VW-Audi, BMW and Mercedes engineers six years ago, because they carried the high cost of two powertrains and a large battery — and diesel was still their preferred propulsion source. Now the German OEMs are introducing PHEVs across their platforms because they deliver range.

“And unlike EVs, they know they can sell PHEVs if they price them the same or slightly more than a regular car and can add-in performance features,” Dr. Anderman said.

A year ago, he forecast that PHEV volume would be bigger than EV, based on input from most OEMs. This year his projection is about the same for the two propulsion modes. Are PHEVs a more practical choice for customers because they offer better functionality than even a 200-mile-range EV?

“The CO2 regulations are pushing everybody — but how much are the auto companies willing to allocate capital, with a risk of no or little return?” he asked. “The companies look at how much regulatory credit they get for a vehicle that costs them $3000 more than their regular vehicles. With EVs this still is not clear.”

EVs might have to be cheaper than a conventional car to sell in volume, beyond the early adopters, he opined. If, for example, Tesla ends up having to sell its Model 3 below cost, “how long can they sustain that? They might be planning to sell a lot of EV credits,” he offered, “but that’s a risky proposition and not sustainable over time.”

There is no comparison between the mobile-devices market and that of electrified vehicles, because “the iPhone is driven by customer demand,” Dr. Anderman said.

Improving the lithium-ion ‘system’

Anderman’s not surprised at the difficulty and failure that various rising-profile battery startups faced to develop lithium ion. He tells their engineers and financial backers that the real test is not technology — it’s manufacturing.

“I don’t care about how your latest anode looks or what is the color of your cathode. Survival in the automotive battery business means getting to high volume, high speed, with a low defect rate and low cost. That’s where Panasonic and the Japanese in general are very strong,” Dr. Anderman noted. “When people tell me they have achieved 10% better energy density in the lab, that isn’t even a factor. What’s important are battery life, safety and the ability to produce cost-competitively in high volume.”

Is there a ‘‘battery breakthrough” coming, as lithium-ion chemistry was in 1991, and nickel-metal hydride was before that?

“Lithium ion put us on a faster improvement curve than we had with NiMH. The great thing about lithium ion is, it’s a system — an umbrella of technology. You can replace the cathode, the anode, the electrolyte, change the shape of the cell and it’s still lithium ion,” he explained.

“I’m a pragmatic person and when I look at all the barriers, versus what you get if you solve them, solid electrolytes for automotive batteries don’t have all that much promise. Because you’re talking less than 50% improvement if everything goes well, and you have a lot of challenges like manufacturability and safety.”

Nor does Dr. Anderman currently see much hope in lithium-sulfur batteries for automotive, due to volume issues and cycle life. He called lithium-air batteries that often garner media attention “a vision that is more complicated than a fuel cell if you look at the technology. Lithium air operates under conditions that you try to avoid with lithium ion.”

Same with lithium-metal: “It’s got all the issues that if you have them with lithium-ion you’ve lost the game.”

Promising auto battery R&D

Silicon and silicon-compound developments, as Tesla has admitted to working on in a new cell with partner Panasonic, interest Dr. Anderman.

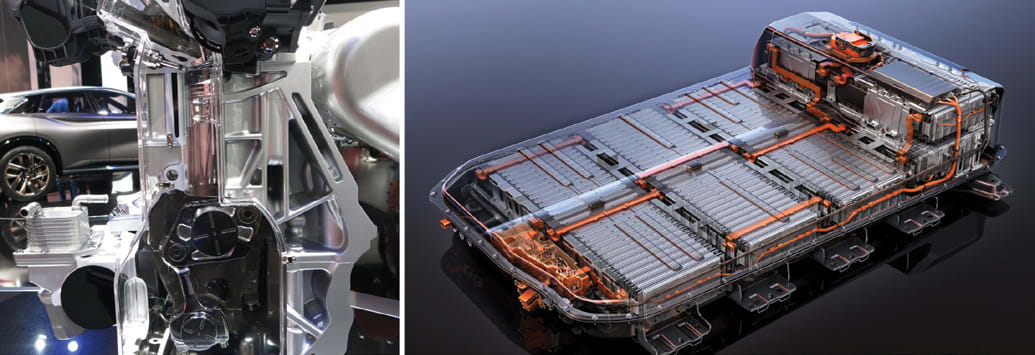

Adding a percentage of silicon to the standard graphite used in lithium-ion battery anodes has the potential to increase the battery’s capacity to store energy and thus help lower the cost per kW•h. Research efforts using silicon to date often have resulted in battery “swelling” and failure, however.

Tesla and Panasonic engineers have been adding 5% to 10% silicon to the anodes of production battery packs, the silicon-graphite anode emerging as a “hot rodding” feature of the electric-car era. For proof of its value, look no further than the $10,000 option price that Tesla is charging for its new-for-2017 P100D pack that delivers a claimed 100 kW•h per charge — an increase from the incumbent 90 kW•h P90D battery available in Model S and Model X.

It really is all about the battery, as Dr. Anderman’s analysis of the industry continues to show.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...