Tracking the Battery-Market BATTLEGROUND

Production scale, yield, and new cell technologies are challenging EV battery-cell suppliers, explains an expert at IHS Markit.

While sales of global battery-electric vehicles (EVs) remain an unfulfilled promise outside of Tesla Motors, their batteries and constituent materials are among the hottest mobility-industry technologies. As a recent report on NASDAQ.com affirmed, “Investors who seek to consider a new arena for investments in the future can look into the global automotive battery market.” Led by electrified vehicle production plans, that market is projected to leap from $49 billion in 2017 to more than $85 billion in 2025—a CAGR of 7.02%.

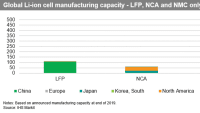

The race is on among lithium-battery Tier 1s to boost global cell-manufacturing capacity to align with their OEM projections for consumer EV demand in the 2025-2030 timeframe. The rise of the battery-cell ‘gigafactory’ is shaping the new-mobility discussion in every global region. Production-capacity leader LG Chem is building a 30 gigawatt-hour-capacity (GWh) plant in Ohio with partner General Motors. Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd. (CATL) expects to have its new 14-GWh battery factory in Germany online in 2022. China alone plans to add 564 GWh of cellmaking capacity by multiple manufacturers by 2028; more than 2 terrawatt-hours (TWh) of battery cell-making capacity would be needed to support global production of 40 million EVs, when that time comes, according to reports.

Cell production yield rates critical

“Establishing scale in battery manufacturing is very important in the period through 2025,” observes Dr. Richard Kim, principal automotive supply-chain and technology analyst at IHS Markit. “At least 5 GWh to 10 GWh of capacity per region will be a minimum scale for production.”

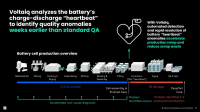

In an interview with SAE’s Automotive Engineering, Dr. Kim noted that although sheer production scale is a critical to driving battery cost down and making EVs more affordable (and profitable), a more important factor for cost reduction is cell production speed and yield rate.

“Cell manufacturers are making significant efforts to speed up their lines with the goal of achieving yield rates greater than 90 percent,” he explained. “But even the top-tier EV battery companies—LG Chem, CATL and Panasonic—are having difficulty in enhancing their process speed and increasing yield rates on each of their production lines.” The combined output of those three suppliers account for about 60% of the total EV cell market.

Dr. Kim said he believes that through 2025, improving in-plant process efficiencies at higher yield rates “may be the greatest challenge facing the second-tier companies—BYD, Samsung SDI and SK Innovation—as well as impacting the emerging start-up battery-tech outfits and “dark horse” third-tier players including SAFT and Northvolt. The challenge becomes more acute as the EV industry moves toward larger battery cells, with fewer cells per pack and cell suppliers’ production lines are increasingly automated. He expects the second-tier makers to have more or less 100 GWh total cell-making capacity around the world by 2025.

“Global light-vehicle OEMs will multi-source their EV batteries going forward,” Dr. Kim said. “Tesla, Volkswagen, Daimler, General Motors, Renault, Hyundai, all the big EV makers are taking this strategy for their sustainable supply-chain establishment—depending on the market, of course. In China, many OEMs including Toyota, GM and Honda are signing contracts with CATL.”

Panasonic, however, is currently viewed as relying on a single big client—Tesla—for the short term. “Looking out to 2025, unless Panasonic finds more clients, or Toyota as a client increases its EV growth as fast as it expects—Panasonic will face difficulties in growth, particularly considering its weak position in China and Europe. Of course, Panasonic could achieve sustainable profit growth in the U.S. if Tesla could maintain such a high market share of battery-EVs, to 20-30 percent!” he added.

Disruptive chemistries

Dr. Kim and the IHS Markit tech analyst team are watching new cell chemistries engineered to improve energy density, safety and charging time—and in some cases, to reduce cost. One of them, the all-polymer lithium battery, uses solid polymer as the electrolyte. A new player, APB Corp., was founded by former Nissan EV engineer Hideaki Horie, to commercialize the all-polymer technology, with partners Yokogawa Electric and carbon-fiber maker Teijin Ltd.

“Various solid-state chemistries are under development at the laboratory level,” Kim noted. “Once this technology is successfully commercialized it will have a big impact. But considering the cost pressure on battery-electric vehicles to compete with ICE vehicles, any cost increases in batteries will be significant.”

Cell makers are continuing to make huge investments in their current lithium-ion capacity around the world, and Kim noted the incumbent cell technology “will dominate the market” through 2030. He stated that current lithium-ion chemistries “are improving through incremental innovation, rather than radical innovation.” This will continue until the new chemistries emerge from the laboratory, are tested and validated, “and there is mass-production technology to support them.”

EV engineers at General Motors tell AEI that before 2030 they expect a shift to less-cobalt-intensive cathode chemistries that employ higher nickel content, along with new anode chemistries including silicon-graphite. Tesla recently announced an incremental change in cell chemistry due to supply-chain limitations in its biggest market. Since no Chinese cell makers produce nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) cells domestically, Tesla has gained approval from the Bejing government to build its Model 3 with lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries. LFP chemistry is less energy-dense than NCA but is deemed safer and less costly. Other OEMs are expected to emulate the move to LFP for China.

Mobility engineers often ask when battery and ICE cost curves cross. It’s not easily answered, Kim admits. “If we consider that for a BEV to have the same driving range [as an ICE] on a single charge, the BEV would need a 150-kWh battery, then it would take until 2030 or later for the cost curves to cross,” he said. However, given equivalent vehicle functionality, an EV with a 60-70 kWh battery could arrive at ICE-cost-parity [in terms of vehicle price] presumably by 2028. IHS Market is working on a study on this topic, the results of which will announced later in 2020, Kim said.

Top Stories

NewsRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsPower

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

ArticlesAR/AI

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Automotive

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Automotive

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Energy

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance