Reinventing the Automobile’s Design

The convergence of electric propulsion, Level 5 autonomy, and the advent of car-free urban zones, is driving new approaches to vehicle design and engineering.

The 2030 view inside the Mobility Industry, towards fully autonomous electric vehicles and robotaxi business models, has swiftly evolved from skepticism towards conventional wisdom. If the current view is correct—and it is being propelled by powerful technology companies and national governments as well as by automakers—then it will have significant implications for all vehicle systems.

Profound changes in vehicle architecture, structure, powertrain, chassis, closures and interior will be driven largely by the increased importance of the user experience (UX) in the personally-owned autonomous vehicle, the different cost structure for operating a robotaxi fleet and, perhaps, by city centers becoming car-free zones.

There will, however, be new sustainability challenges posed by this paradigm shift. And the answers, ironically, could be pioneered in the poorest parts of the world.

Personal ownership

Let us first consider the personally-owned automobile that has SAE Level 5 autonomy but must still co-exist with other vehicles on the road. For this reason it will still need to meet U.S. FMVSS and other global safety requirements.

Once the public is convinced that such a vehicle can deliver safe and secure autonomous driving operation it is likely that customer differentiation will center on the user experience. Control (of powertrain and chassis) and design (of exterior and interior) will be developed with the goal of supporting a compelling UX. One measure of this will be that all passengers leave the vehicle feeling more content and relaxed than when they entered it.

For example, routes may be selected that minimize driving on bumpy roads and sharp bends while more sensors may be integrated into each seat for monitoring the passengers. The vehicle might automatically provide a soothing welcome, manage simple but time-consuming appointment scheduling, suggest infotainment options and help with preparing for the next activity. Displays that enhance viewing of consumer electronic device content while being as convenient to use under all ambient lighting conditions will become a new area of competitive differentiation.

With an aging population in many regions there could be more at-risk passengers sitting alone inside moving automobiles. Therefore, the capacity to monitor passenger health and wellness will become increasingly important. Cabin sensor suites will handle the monitoring, provide confidential feedback, and enable the vehicle to respond appropriately. Mitigating actions that the vehicle might take include adjusting displays and ride motion (to prevent the onset of motion sickness) and contacting local medical providers in emergency situations.

Daily health monitoring in the same mobile environment can also provide valuable healthcare data and early detection of abnormal health signals.

Rise of the robotaxi

Another scenario that is being developed in parallel with the personally owned autonomous vehicle is the “robotaxi” (i.e. taxi without taxi driver). Robotaxi fleet operators will strive to lower operating costs and so vehicle design changes that support this objective will be required.

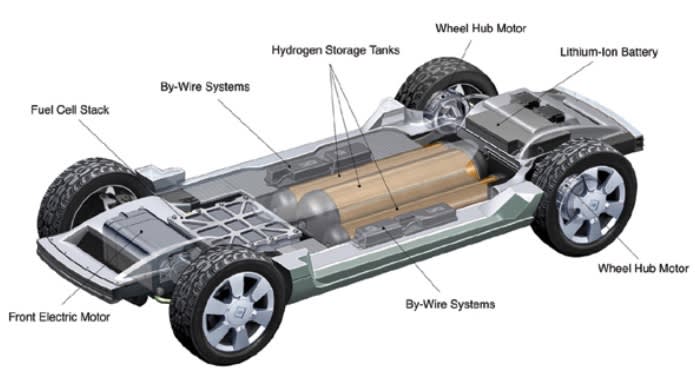

Reducing the cost to recharge, since robotaxis will likely have electric drive, and reducing the need for maintenance (e.g. easy to clean interior surfaces and remote monitoring and diagnostics of all vehicle systems) will be key to creating a profitable business model. But there are other, less obvious, implications. Vehicles that can operate in both directions (since a robotaxi that leverages a “skateboard” architecture need not have front or rear ends, per se) can reduce traffic congestion and “dead time” caused by maneuvering to pick up and drop off passengers or cargo. Increased maneuverability might also enable more route options to reduce travel time, particularly in dense city centers with narrow streets.

Leveraging the vehicle platform to perform both passenger and cargo transport around the clock will increase utilization and further improve the operator’s business model. This flexibility can be achieved in several ways. For example, the vehicle may be reconfigurable with fold-down seats to provide additional storage when needed. Or the vehicle’s skateboard platform could facilitate dedicated pods that can be switched at night between passenger cabins and cargo containers.

Automotive and heavy-duty truck designers and interior-systems Tier 1s are already exploring future cabin concepts. Aerodynamic drag and energy consumption may be reduced if vision angles can be relaxed. Inside the cabin, additional free space can be afforded by deleting the steering column, transmission and brake/ throttle controls and other driver-focused necessities.

In addition to reduced operating costs and increased utilization, a third reason for rethinking robotaxi design will be to lower infrastructure-related capital costs. A fleet operator will probably want to park the fleet in as few locations as possible over-night, since vehicle maintenance and recharging may be easier to accomplish. Escalating real-estate costs, currently exceeding $1,000/m2 in major city centers, are also driving the need to pack vehicles into smaller lots. Technology solutions such as in-wheel traction motors can help decrease a vehicle’s turning radius, thus helping to reduce the wasted space in a parking lot required for vehicle maneuvering.

‘Zero-crash’ designs

A growing number of cities in Europe, including Brussels, Vienna, Prague, Frankfurt, Rome, St. Petersburg and Birmingham, are establishing car-free city centers to improve quality of life. Dozens of other cities are contemplating similar legislation, including congestion taxes. This trend is already driving development of new types of vehicles that can co-exist more harmoniously with vulnerable road users (i.e., pedestrians and cyclists) and require less space for parking. (The same result can also happen if all vehicles are required to operate at low speed in geo-fenced areas and are equipped with autonomous capability so that they do not cause harmful collisions.)

Even if places become car-free, vehicles will still be required to provide door-to-door mobility in all weather conditions for all people, including the aged and disabled. However, by not having an automobile’s mass, size, range and speed they can be smaller, lighter, less expensive, capable of using readily available materials and built with local labor, creating high quality jobs inside the city.

Vehicles that do not need to meet crash requirements can be engineered to employ materials that are optimized for cost, mass, recyclability, local availability and aesthetics. Moreover, novel solutions for passenger ingress and egress can be enabled, such as front entry (pioneered by the ‘bubble cars’ of the 1950s!). This can help the elderly while also potentially improving safety—no more opening the side door in the middle of the street and trying to avoid being hit.

To illustrate the dramatic changes possible, consider one vehicle subsystem: cabin climate control. The seats and instrument panels in today’s automobiles are significant heat sinks; rapidly cooling them after a hot soak demands an HVAC system capable of heating and cooling a small house. If glazing systems don’t need to provide the same visible light transmission, engine waste heat is not available and crash structure and long-journey comfort requirements are not required, then the centralized forced-air system could shift towards radiant floor heat and focused cooling. Overall, such a shift in HVAC design and performance will help enable vehicle designs that are more compact and energy efficient.

Sustainable mobility challenges

As vehicle autonomy enables greater personal mobility for the disabled and elderly, and as robotaxis provide affordable transport to everyone, there is a risk that this will cause more road congestion—and consumption of more energy by transportation. There may be more strain on the electric grid, particularly on summer days, as electric vehicles charge opportunistically between rides.

Vehicles driving hundreds of miles per day will have shortened life cycles and create huge surpluses of used batteries. Meanwhile, the rise of robotaxis (and fully autonomous vehicles in general) could threaten, if not eliminate, many transportation jobs in the long term.

One solution is to optimize the size, mass, speed and range of these vehicles for their local environment. Such dedicated design and engineering would allow these low speed vehicles to re-use batteries from electric vehicles at end of life. A used 2.5 kW·h 48-V battery module from a Chevrolet Volt, for example, still retains abundant energy and power for low-speed vehicle applications and could provide 50 miles’ (80 km) range for a very small vehicle.

In many parts of the world like Africa and India, much of this daily energy could be generated from a solar panel roof on the vehicle itself since the grid may not be reliable or even accessible. Each community could even design, develop and manufacture these vehicles locally from used vehicle parts and readily available materials. Instead of relying on global auto-makers, these inner cities and communities can create high-quality jobs to offset employment losses from automation.

In regions where there is no electric grid, mobility solutions demand consideration of solar energy. And to be practical, the vehicle’s energy demand must be extremely low. The advent of low speed, lightweight solar powered electric vehicles that incorporate re-used lithium-ion batteries and repurposed car parts, to help make the vehicle affordable, is a paradigm shift that may be required in the poorest parts of the world.

Zero-crash vehicle designs, enabled by autonomy and car-free communities are on the drawing board in developed regions and can help to support a similar vision so that employment, sustainability, accessibility and economic development are achieved together for all the World’s people.

Dr. Chris Borroni-Bird is co-author of Reinventing the Automobile: Personal Urban Mobility for the 21st Century, with Dr. Larry Burns and the late Prof. Bill Mitchell (MIT Press, 2010). He retired as Qualcomm’s VP of Strategic Development in 2017 to focus on global sustainable-mobility solutions and is founder of Afreecar LLC, with a half-time appointment at MIT Media Lab. At GM he led development of the forward-looking EN-V, Autonomy, Hy-wire and Sequel projects. In the 1990s Dr. Borroni-Bird led Chrysler’s gasoline fuel-cell vehicle project. He holds 50 patents, many related to the ‘skateboard’ platform concept.

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance