Enterprise Battery-Analysis Pioneer Voltaiq Partners with Siemens

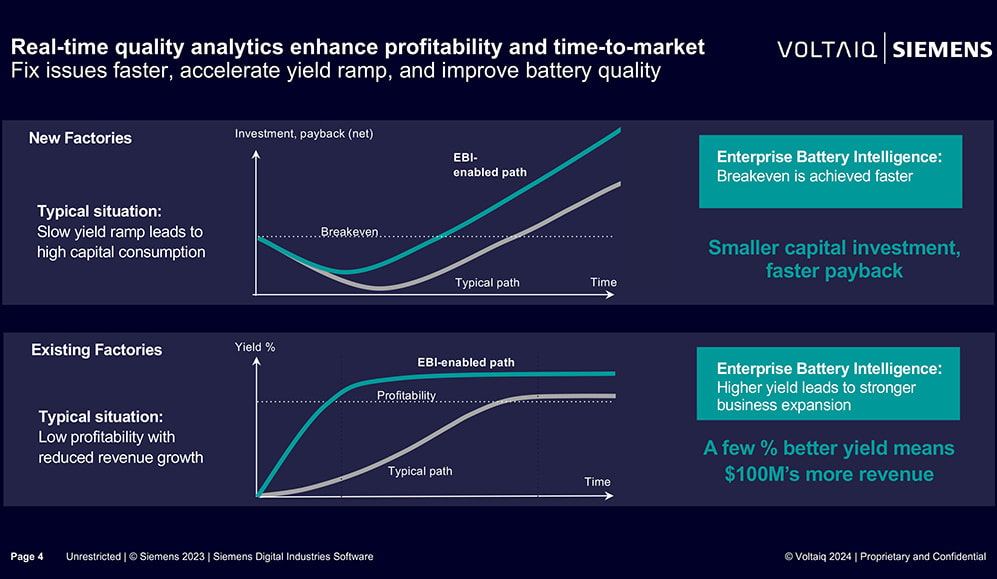

The partnership was forged to help more battery manufacturing plants improve processes more quickly to reach higher good-battery yield rates and in turn profitability.

As CES 2024 was wrapping up in Las Vegas, battery-analysis pioneer Voltaiq and Siemens Digital Industries Software announced a partnership they said is intended to help battery manufacturers speed up the iterative process of improving yield rates.

Some new battery plants, particularly those started by OEMs, begin with scrap rates as high as 90%, said Tal Sholklapper, CEO of Voltaiq. Voltaiq’s enterprise battery intelligence platform can reduce that number by tracking thousands of data points during the manufacturing process and helping factories intervene on bad cells sooner. The companies stated in a news release that the industry is forecasting a 14-fold increase in battery demand through 2030 but only a five-fold increase in battery cell production through 2030 for EVs alone.

Speaking to a group of journalists that included SAE Media, Sholklapper said it has taken some battery plants “four years, at a cost of billions of dollars, to achieve a 10% scrap rate.” He added that at that point, a few percentage points of yield improvement can mean hundreds of millions in revenue. Siemens brings its deep experience in systems that monitor and control manufacturing processes, such as with programmatic logic controllers (PLCs). Such controllers can automatically make small adjustments in the chemical and physical processes of building battery cells and packs based on Voltaiq’s data analysis. What it all translates to is being able to halt and fix a problem earlier in the manufacturing process, resulting in less time and money lost.

“We’ll take the insight from Voltaiq and put it into the control process, making it a fast iterative loop,” said Raymond Kok, Siemens’ senior vice president of cloud application services. Sholklapper said Siemens’ reach and stature in the business could more quickly help make more manufacturing plants better. “They have the scale to help this go global,” he said. The companies said the partnership would help in five areas: quality control/consistency, increased production, process efficiency, waste reduction and high costs.

Unlike most manufacturing, where there can be a “set it and forget it” approach to production, batteries are incredibly complex, almost like living things. “Battery making is dozens of processes that have extremely narrow tolerances,” said Eli Leland, Voltaiq’s chief technical officer. Leland also said that these long new-factory learning curves are not new. “It took us 125 years to get the internal combustion engine to run for hundreds of thousands of miles without problems,” Leland said, adding that there just isn’t a ton of modern battery expertise, particularly at some OEMs. “The core competency here is learning how to learn,” he said.

Why greatness takes so long

Sholklapper said that the manual process of testing newly manufactured batteries takes too long. “Batteries are made, charged and discharged multiple times, and then put in a hot room for up to three weeks. If the voltage drops, there’s a short somewhere in the batteries, which means you have to fix it. And as you’ve been making batteries for three weeks, then they all may have to be scrapped.”

The goal of the partnership will be to marry Voltaiq’s and Siemens’ software to allow corrections to be made more quickly, before three weeks or a month or more of manufacturing time and money are lost.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...