Purpose, Perceptions for Driver-Assist Tech Solidify

Panelists at SAE's 2021 Government/Industry Meeting say driving-assist technology is worthwhile, but only if it gets better and more widely available.

A panel of automated-driving experts at this week’s virtual presentation of SAE International’s annual Government/Industry Meeting had strong opinions on the current state of advanced driver-assistance system (ADAS) technology. Although most concurred that so-called “low-level” assisted-driving technology (usually referred to as Level 2 in the SAE Standard for levels of driving automation) can enhance safety and help to prevent accidents, there is considerable variation in functionality and user interface. This has fostered consumer confusion and mitigates the technologies’ potential, they noted.

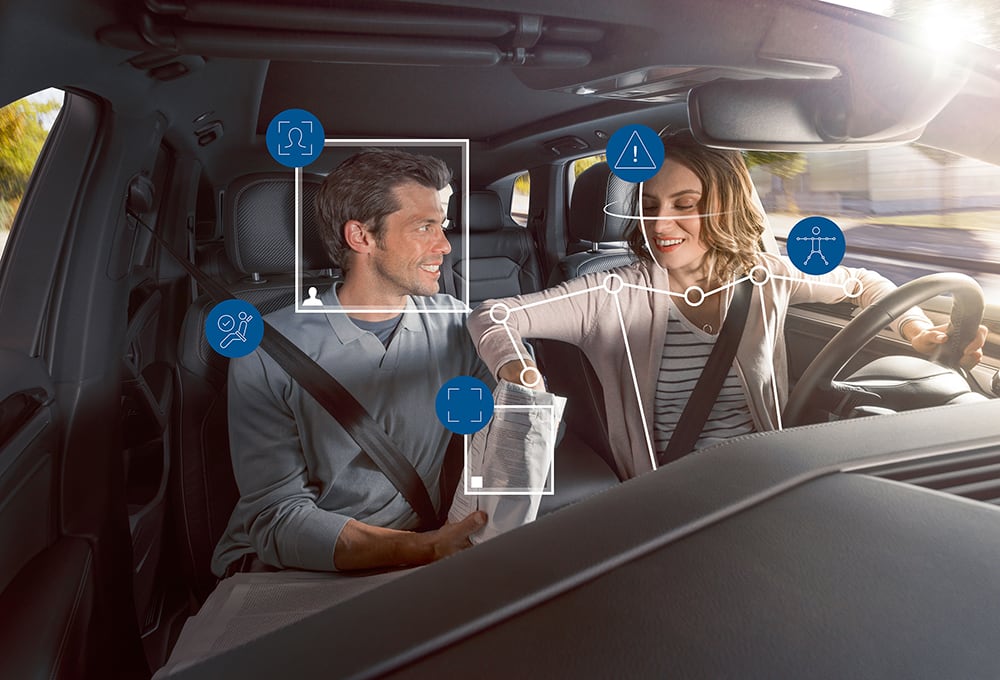

The “Leveling Up: Path to Increased Driver Assistance” panel stressed one crucial point: to derive maximum effectiveness from Level 2 assisted-driving technology – such as automatic emergency braking (AEB) and pedestrian detection, lane-keeping assist (LKA) or Level 2 integrated systems such as Cadillac’s Super Cruise or Nissan’s ProPilot Assist – a stringent driver-monitoring system (DMS) is crucial for ensuring the driver is attentive. Some on the panel suggested regulators in the U.S. and Europe should fast-track either a voluntary agreement or an outright requirement for automakers to fit DMS in every ADAS-equipped vehicle. .

Level 2: promise mixed with problems

“I think the story for Level 2 is still kind of blurry,” said David Zuby, executive VP and chief research officer at the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS). He said that for both passenger vehicles and commercial vehicles, studies have indicated definitive accident-reduction potential for features such as AEB and LKA, in particular. And “early data” show possible positive impact for adaptive cruise control, too.

But that potential is countered by a wide variance in system performance and driver-interface efficacy that is hindering driver-assistance technology’s impact, many on the panel said. Poor driver-interface design shapes system effectiveness and also can lead consumers to disable the function entirely, said Zuby. He added that studies have indicated deactivation rates as high as 70% for LKA, a feature that seems to have an outsized potential annoyance factor. "Intervention needs to be perceived as useful — and not too late."

Ironically, good systems have a downside, too: fostering driver inattentiveness or even outright abuse. “We need to help the driver, moment-to-moment,” asserted Bryan Reimer, research scientist at MIT. Ill-designed functions that permit lags as long as several seconds in alerting the driver “are not acceptable,” he said, while good systems also need a viable method to assure driver attentiveness. “We have to mitigate the abuse — and misuse — of automated-vehicle technology,” he said.

“We don’t need a debate on this,” Reimer added, calling driver-assistance features “the intersection of safety and convenience.” He suggested quick auto-industry and regulator action for a voluntary agreement or regulation to require a DMS when assist features are activated. Interior cameras have emerged as the most viable DMS solution and already are in use by many automakers. Increasingly sophisticated camera software not only can reliably monitor attentiveness, but also detect drowsiness or impairment, while also monitoring the cabin for other distracting behavior or situations.

Kelly Funkhouser, head of advanced vehicle technology at Consumer Reports, concurred, saying “it’s the responsibility of automakers” to equip vehicles with effective and vigilant driver-monitoring technology if Level 2 functions are available, noting that some current DMS can be easily duped or disabled. “Effective, direct driver monitoring” should be an industry priority as driver-assistance features become more ubiquitous, she stressed.

Regulation’s role

Richard Schram, technical director at Euro NCAP, cautioned that although consistent and effective standards and regulation for assisted-driving technology are important, regulators must endeavor to avoid regulations that “push manufacturers to design systems that aren’t used by or please consumers.”

The National Highway Traffic Safety Admin.’s (NHTSA) Garrick Forkenbrock acknowledged the disarray of the current Level 2 environment, but also advised caution in however the industry proceeds. “Establishing [a safety regulation or standard] “without appropriate knowledge is something we need to take pretty seriously,” he said. MIT’s Reimer added that the regulatory sector itself also could benefit from a revised structure to better address the challenges of emerging ADAS and high-level automated-driving technology.

“We need an agency that is looking at automation across [transportation] modes,” Reimer said. He said an improved regulatory mechanism requires personnel with wider knowledge of automation and how it is being applied in a variety of sectors.

Reimer suggested a structure for automated-driving technology regulation could consider a model similar to the U.S. Food and Drug Admin. (FDA) approval process for new drugs, a system of “prove to me that it works,” before the technology is cleared for consumer use.

More examination of SAE Level 3

Meanwhile, the controversial Level 3 of SAE’s driving automation hierarchy continues to spark debate. Many industry, research and regulatory entities assert Level 3’s higher reliance on automation — and the crucial action of automation “handoff” to the driver in situations beyond the system’s ability – is a development dead-end. Some panelists at the SAE Government/Industry Meeting indicated that given today’s helter-skelter environment for Level 2 implementation, the complexities of Level 3 may make for diminishing returns.

“There is no need for Level 3,” MIT’s Reimer flatly asserted. “Level 3 systems are likely only to enhance confusion even more.” He said SAE Levels 2 and 4 — the latter representing fully automated driving under most external conditions — are sufficiently complicated and that Level 3’s general fusion of the Levels 2 and 4 may serve no productive purpose.

The panel said the incoming Biden Administration could foster an improved industry-regulatory environment by increasing research funding that would speed the time to market for “acceptable” assisted-driving technology. Consumer Reports’ Funkhouser also suggested the new administration should revisit a late-2020 decision from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that apportioned to Wi-Fi use a section of the 5.9 GHz “Safety Spectrum” bandwidth formerly reserved for transportation-industry safety communications.

More-sophisticated driver-assistance technologies, as well as the path to SAE Level 4 and 5 automation, will be reliant in varying degrees to the vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communications that use the Safety Spectrum bandwidth. But those engineering high-level automated driving systems generally agree that the functionality of those systems must be executable from onboard capabilities and cannot be dependent on having communication with external resources.

Top Stories

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsPower

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERDesign

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesAR/AI

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

Road ReadyDesign

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Automotive

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Transportation

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Energy

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance