Low-Power Distributed Jammer Network

MEMS technology is used to create a low-power distributed jammer network that protects wireless networks from denial-of-service attacks.

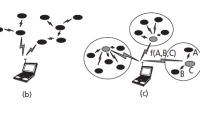

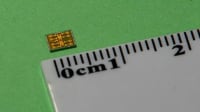

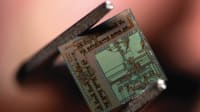

The Distributed Jammer Network (DJN) is composed of a large number of tiny, low-power jammers, which are distributed inside a target network and emit radio energy to disrupt its communications. Recent advancement in microelectromechanical system (MEMS) technology makes it possible to make jammers sufficiently small that a DJN can take the form of a dust suspending in the air, thus the name Jamming Dust. Miniaturization of jammers should be less challenging than that of wireless sensors since jammers just emit noise signal without requiring complex modulation, filtering, and other signal processing functions. Therefore, new miniature devices such as nanotube radio may find their first application in jamming dust.

Advantages of DJN are reminiscent of those of DSN. First, DJN is robust because it is composed of a large number of devices with ample redundancy. Second, DJN nodes emit low power, which is advantageous because of health concerns. Third, DJN is hard to detect because of the nodes’ small size and low power emission. Fourth, DJN provides extended coverage with high energy efficiency. Using the same total amount of power, a DJN of n nodes covers an effective area n1-2/α times larger than that of a single jammer, where α is the path loss exponent with a typical value of 4. So the typical power efficiency gain of DJN is n1/2, which is unbounded as n goes to infinity.

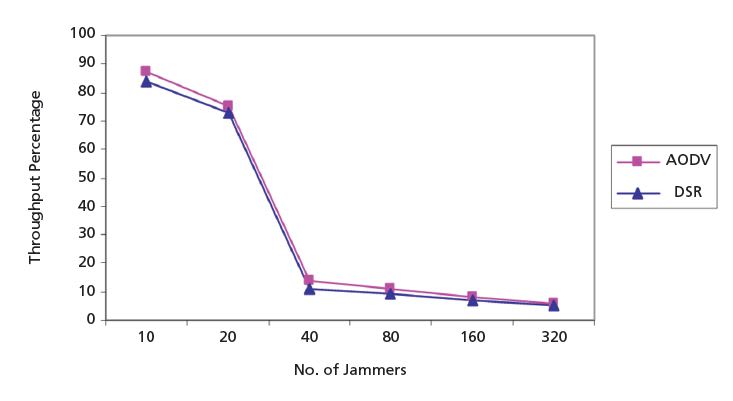

A simulation was performed with the following setup: The target network (DWN) has 100 nodes deployed in an area of 1000 by 1000 meters, with half of the nodes having CBR UDP sessions with the other half of the nodes. The MAC protocol used is IEEE802.11, and two routing protocols are used – AODV and DSR. Ten jammers were deployed with the same transmitting power as the target device (15 dbm). Then, the number of jammers was increased while reducing jamming power, holding the total power consumed by the jammers constant. The performance metric is the ratio of DWN throughput with jamming, versus that without jamming. A phase transition occurs at roughly 20 jammers, where throughput ratio drops precipitously. Given that the total power consumption is constant, the benefit of using a large number of lowpower jammers (i.e., DJN) is evident.

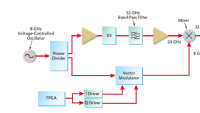

As for the jamming mechanism, it is assumed that jammers in DJN are reactive jammers, which are among the most effective jamming methods. A reactive jammer senses a wide frequency range and jams the channel on which it detects radio activity. Recent advancement in software-defined radio and UWB radio provides technology to make such jammers. The jammer has two parameters: period P and duty cycle D. That is, after sensing a busy channel, a jammer becomes active in D percentage of time in a period of P seconds, after which the jammer restarts sensing again.

It is assumed that transmission powers of both DWN and DJN radios are adaptable up to their respective maximum transmitting powers. If the maximum transmitting powers of DWN and DJN nodes are the same, a DWN receiver is considered jammed if there exists a DJN jammer that is closer to the receiver than the DWN transmitter. In such a case, the jammer can always adapt its power to overpower the transmitter; however, the transmitter adapts its own power.

This work was done by Hong Huang, Nihal Ahmed, and Santhosh Pullurul of New Mexico State University for the Army Research Laboratory. ARL-0130

This Brief includes a Technical Support Package (TSP).

Low-Power Distributed Jammer Network

(reference ARL-0130) is currently available for download from the TSP library.

Don't have an account?

Overview

The document presents a research paper titled "Jamming Dust: A Low-Power Distributed Jammer Network," authored by Hong Huang, Nihal Ahmed, and Santhosh Pulluru from the Klipsch School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at New Mexico State University. The paper introduces a novel type of denial of service attack on wireless networks, utilizing a Distributed Jammer Network (DJN) composed of numerous tiny, low-power jammers. These jammers can be miniaturized to the extent that they resemble "jamming dust," leveraging advancements in MEMS and NANO technology.

The authors argue for a networked perspective on jamming attacks, contrasting traditional views that focus on individual jammers. They demonstrate that a DJN can induce a phase transition in the performance of the target network, significantly affecting its connectivity. The paper employs Percolation Theory to analyze this phase transition, providing both lower and upper bounds for network percolation in the presence of DJN. Additionally, the authors discuss the scaling relationships between the intensity of jammers and their power constraints.

The paper outlines various applications of DJN, highlighting its potential in military and security contexts. The low-power, distributed nature of DJN makes it an attractive option for modern warfare, where stealth and reduced self-interference are crucial. The authors reference historical instances, such as the second Iraq war, to illustrate the importance of self-interference-free jamming in military operations.

On the civilian side, the paper acknowledges the legal restrictions on jammers in the United States, where their use is illegal. However, it notes that in some countries, jammers are employed for practical purposes, such as silencing cell phones in restaurants, preventing cheating in exam rooms, and maintaining decorum in churches. The authors argue that a low-power DJN would be preferable in these scenarios due to its reduced visibility and impact.

In conclusion, the paper emphasizes the significance of DJN in both military and civilian applications, advocating for further exploration of its capabilities and implications in the context of wireless communication disruptions. The research contributes to the understanding of jamming technologies and their potential effects on network performance and security.

Top Stories

INSIDERDefense

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

Road ReadyTransportation

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Power

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Connectivity

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Transportation

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Aerospace

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance