AUSA 2025: Secretary Driscoll Wants Army to Save Time and Money by 3D-Printing Replacement Parts

U.S. Army Secretary Dan Driscoll's brutally honest keynote speech to open AUSA's 2025 annual meeting included a focus on how much money the Army could be saving on replacement parts for its Black Hawk helicopter fleet by embracing 3D printing. The secretary also said the Army needs to embrace artificial intelligence (AI) and wants soldiers to be able to assemble drones and have access to the most cutting edge off the shelf technologies that are available.

The secretary's speech was heavily focused on how much outdated and obsolete technology that the Army still operates on a daily basis. Driscoll believes that the way the Army invests in new technologies needs to shift away from the current process that includes too many regulatory hurdles, and instead focus on getting the best cutting edge technologies to soldiers in combat as soon as possible.

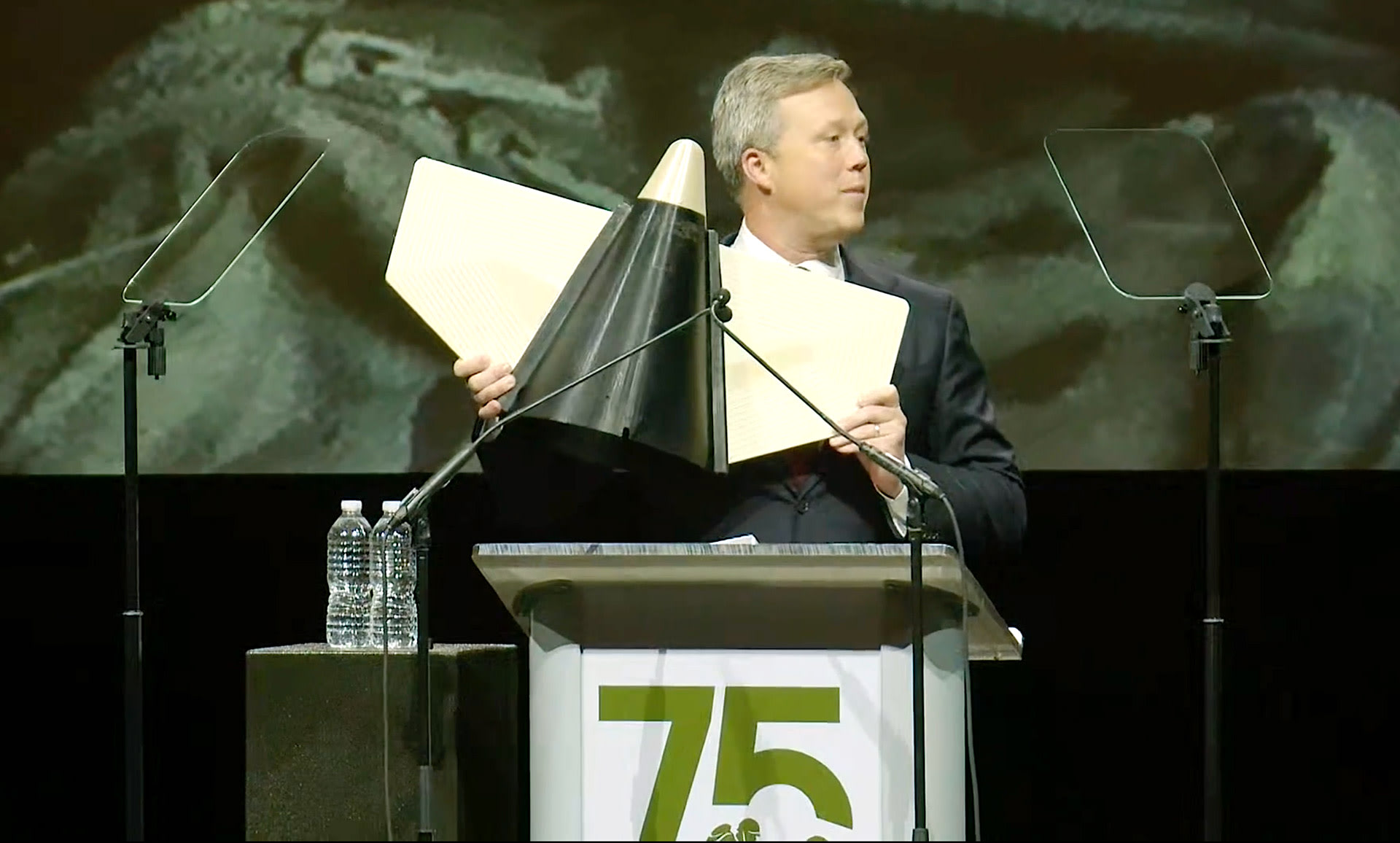

With additive manufacturing however, Driscoll said the Army is currently focused on leveraging the technology for repairs and replacements of parts, mainly for in-service aircraft, helicopters and ground vehicles. At one point in the speech, Driscoll held up a 3D-printed part from a Black Hawk helicopter and compared the cost the vendor charges the Army to replace it to the cost of the Army engineers printing it.

"This is the fin for a Black Hawk’s external fuel tank. They are built cheap, so they break often. The vendor charges over $144,000 for replacement. Our team can do it better. They 3D-scanned the part, reverse engineered it, printed prototypes, and conducted structural validation in only 43 days. The part I'm holding is their floor prototype. Now, we can manufacture this part for just over $3,000," said Driscoll.

One of the major factors that leads to higher costs for the Army is their inability to repair most of the aircraft and vehicles that they purchase and operate. Gaining more ownership over the repairs of Army assets such as the Black Hawk was one of the highlights of Secretary of War Pete Hegseth's "Army Transformation and Acquisition Reform" memorandum that he issued in April advocating for major reforms to the Army's acquisition process.

“Identify and propose contract modifications for right to repair provisions where intellectual property constraints limit the Army's ability to conduct maintenance and access the appropriate maintenance tools, software, and technical data - while preserving the intellectual capital of American industry,” Hegseth wrote in the memo.

Gaining more right to repair agreements is an initiative that leadership at the Army's Communications-Electronics Command (CECOM) Integrated Logistics Support Center (ILSC) is working on right now. An update provided by the Army in August on CECOM's efforts to expand right to repair states that these changes can primarily occur through new cataloging procedures and technical manual developments that will be a part of future purchases.

Right now however, Driscoll is ultra-focused on leveraging additive manufacturing for repairs and replacements of Black Hawk parts specifically.

"Ours is 300 percent stronger and 78 percent cheaper, and we can ramp up supply in less than six days," Driscoll said, further comparing the Army's 3D-printed Black Hawk external fuel tank fin compared to the vendor-provided replacement part.

Driscoll also compared the costs of 3D-printed replacements for other vendor-provided Black Hawk parts. Next, he showed the AUSA crowd the small screen control knob that Black Hawk pilots use to scroll through aircraft data.

"We break around four of these every single month. When this little tiny thing breaks, the whole aircraft is grounded. The vendor won't produce replacements. So instead, we have to turn in this entire screen assembly and pay $47,000 for a replacement. $47,000 to replace this assembly when we can make this knob for 15 bucks," Driscoll said. "That is a 313,000 percent markup, and we're spending around $188,000 every month for what we could solve for $60. Now, multiply this across thousands of components and you see why our $185 billion budget simply doesn't buy enough combat power. And in some cases, the parts take literally years to arrive."

Over the last year, the Army has continued to work with suppliers of additive manufacturing machines to prove the effectiveness of using 3D-printed replacement parts. In August 2024 for example, the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM) participated in an additive manufacturing training and demonstration event at the University of Tennessee Knoxville. The demonstration trained Army soldiers on the use of additive machines provided by SPEE3D, a Melbourne, Australia-based provider of cold spray 3D printing machines. The demonstration trained the soldier on the use of SPEE3D's machines to 3D print replacement transmission mounts for the Bradley fighting vehicle .

In March, the Army's Rock Island Arsenal-Joint Manufacturing and Technology Center (RIA-JMTC) published an update on its progress with embracing additive manufacturing for repair and replacement parts. The update showed how the RIA-JMTC team has proven its ability to re-engineer and 3D print a two-piece burner cone as a single piece using a stronger material. In August, the Army highlighted a team called the Hawkeye Platoon whose soldiers have learned how to design and 3D print their own first person view (FPV) drones for $400 - $500 in just a few hours.

Driscoll said that in addition to 3D-printed replacement parts, he also wants more Army soldiers to be capable of designing, printing and assembling their own FPV drones.

"We're accelerating advanced manufacturing across the entire Army and leveraging partners who want to help our soldiers. Once we have the schematics, private industry can help surge production if demand surpasses what the Army can produce itself. For certain parts, soldiers will be able to download the schematics, manufacture it, and install it, all in the field," Driscoll said. "This is about more than money. This is an issue that is undermining our national security. It is imperative that we have a right to repair, and we need modular, open architecture systems where repairs are as easy as printing a part or buying one off the shelf."

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...