Are Military Avionics Systems Ready for Artificial Intelligence?

Advancements in embedded processing, software, new product introductions, partnerships and recent demonstration flights reflect the growth in development of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) for military aircraft avionics systems occurring in the aerospace industry. This article highlights trends across several industry partnerships, demonstration flights and the enabling elements that are providing opportunities to integrate AI and ML into military avionics systems.

In a June press release, Helsing, the Munich, Germany-based native software company and Saab, the Swedish defense manufacturer, announced their completion of a series of test flights where Helsing’s “Centaur” AI agent controlled the aerial movements of a Gripen E fighter jet. AI agents are growing in popularity across many different industries for a variety of use cases. In a November 2024 blog about the topic, Microsoft described them as taking “the power of generative AI a step further, because instead of just assisting you, agents can work alongside you or even on your behalf. Agents can do a range of things, from responding to questions to more complicated or multistep assignments. What sets them apart from a personal assistant is that they can be tailored to have a particular expertise.”

Established in 2021, Helsing’s specialty involves the development of AI and ML models and algorithms that can be trained on data from existing defense platforms and sensors, and then integrated into aerospace and defense systems to serve as a data-cruncher, navigation assistant or — in some cases — a decision maker. Centaur is one of several AI agents developed by Helsing through the use of “scaled reinforcement learning,” according to their website.

Reinforcement learning is effectively an application of machine learning where an autonomous agent is developed by repeatedly interacting with a specific simulated or real environment, according to a definition of the term provided by IBM. “In reinforcement learning, an autonomous agent learns to perform a task by trial and error in the absence of any guidance from a human user,” IBM notes in their March 2024 website article, “What is Reinforcement Learning?” In Helsing’s example, this involved exposing their Centaur AI agent to the Gripen E’s aerial combat environment, observing and analyzing data collected by the jet’s assortment of sensors and learning from the recorded and real-time actions of human pilots

A video clip published to Helsing’s website, shows in-flight footage from a Gripen E pilot flying the aircraft, raising his hands and watching Centaur control the Gripen. Centaur also demonstrated its ability to give fire commands to the pilot while flying against another human-controlled Gripen jet. The reinforcement learning process required to train the Centaur agent was six months.

While all of Helsing’s work primarily focused on software model training, integration with Gripen E application programmable interfaces (APIs) and testing, Saab actually set the groundwork for operating a software-defined aircraft several years ago with an overhaul to the Gripen’s avionics. On the Gripen E, which achieved its first delivery in 2019, Saab features a distributed integrated modular avionics (IMA) architecture, where the integration of sensor and actuator functionality on the jet is achieved in a layered approach rather than the traditional siloed structure traditionally featured in military avionics systems.

Further, the Gripen’s avionics system separates 10 percent of the aircraft’s flight critical management codebase from 90 percent of its tactical management code, resulting in avionics that are “hardware agnostic,” according to Saab’s website. This allows the flight critical software to keep performing the most important basic navigation function of the aircraft, while that tactical management codebase can be more easily upgraded with new features such as the integration of Helsing’s Centaur AI agent. Saab describes this as a “split avionics” architecture.

The way the Helsing-Saab collaboration resulted in a flight test where an AI agent controlled a fighter jet took a similar path to a similar demonstration involving the U.S. Air Force. In May 2024, when then U.S. Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall did a demonstration flight in the X-62A Variable In-flight Simulator Test Aircraft (VISTA), the AI agent that flew the aircraft autonomously was also developed using reinforcement learning. The VISTA X-62A program made global industry headlines upon announcing its first real-world flight of the X-62A — a heavily modified F-16 fighter jet — under the control of an AI agent in February 2023. That agent was originally developed through reinforcement learning by a company called Heron Systems Inc.

Heron first developed the AI agent that flew the Secretary of the Air Force on an F-16 last year as part of a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) competition, the “AlphaDogfight Trials,” in 2020. Heron was one of eight companies that spent less than a year training their AI agent to fly in simulated aerial combat missions. Then, as part of the actual trials, the agents competed against each other and then in a dog fight against a real Air Force F-16 pilot in an F-16 simulator. Heron’s AI agent defeated the agents from all seven other companies and the human pilot. Shield AI acquired Heron a year after the completion of the trials.

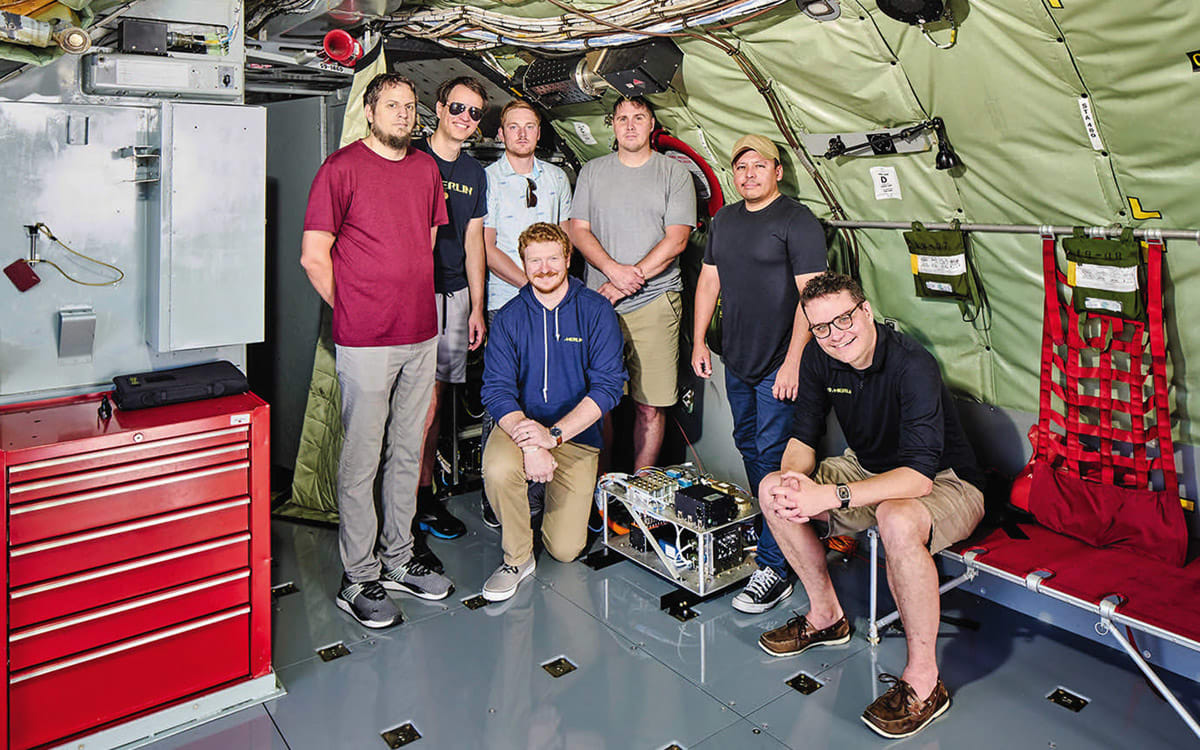

Merlin is another software-first startup developing AI software for military avionics. Founded in 2019, Merlin’s headquarters are in Boston, Massachusetts, while its test facilities are in KeriKeri, New Zealand. The startup’s website outlines a three-step plan for its AI software to go from its current stage of research and testing, to becoming a non-human replacement for a co-pilot and eventually performing uncrewed flights. Merlin has performed several autonomous flights of its Merlin Pilot AI software on a modified demonstration Beechcraft Caravan, and is working with the U.S. Air Force on prototype versions of Merlin Pilot for the C-130J and the KC-135.

Much like Helsing and Shield AI, the startup is collaborating with aircraft and avionics manufacturers on the integration of its software into flight control systems, and is completely software-focused.

“Merlin is not building any hardware components –– rather, we’re building certifiable, high-assurance autonomy on a robust, edge-compute hosted software stack,” Merlin CTO Tim Burns told Aerospace & Defense Technology (A&DT) in an emailed statement. “The system features integrated runtime assurance, anomaly detection, and fail-safe logic, which encompasses human operators (ATC), perception (sensors, weather, traffic, etc.), and high integrity flight autonomy through navigation, flight controls, failure detection, and more.”

The startup gives an overview of how the Merlin AI Pilot works on its website, using a basic four engine military air transport aircraft as an example. The overview notes that the software uses the aircraft’s sensors to understand the state of the aircraft and the flight environment that it is operating within. Leveraging sensor data, the software acts as the brains of the aircraft and decides what actions to take based on the environment and pre-programmed flight plan. The software is also capable of controlling the aircraft’s actuators like a pilot’s hands, and is able to manage the yoke and push buttons or flip switches as needed.

“It uses a combination of pre-programmed deterministic elements with bounded AI/ML capabilities for adaptive decision-making that can be applied to pilot assist, workload reduction, and fully autonomous operations,” Burns said. “Examples of how we apply these methods include using natural language processing to communicate with air traffic control and autonomously react to ATC directives, as well as using computer vision to provide situational awareness by identifying obstacles, runways, and visual cues to support safe navigation and landing. High-assurance systems continuously monitor and validate AI/ML decisions (such as navigating weather or other dynamic environmental conditions), rejecting unsafe actions and maintaining safe flight states.”

In February 2024, Merlin signed a multi-year agreement with the U.S. Air Force to design, integrate, test and demonstrate aspects of Merlin Pilot on the Stratotanker, a goal that could occur this year.

Other industry partnerships are taking different paths toward enabling autonomous and AI-assisted flying.

In October 2024, Honeywell Aerospace announced a collaboration with Near Earth Autonomy (NEA) to demonstrate the ability to autonomously fly a Leonardo AW139 as part of the U.S. Marine Corps Aerial Logistics Connector (ALC) program. NEA, founded in 2012, specializes in providing autonomous navigation software and hardware for a variety of different aircraft types. The partnership between the two companies resulted in the completion of an autonomous demonstration flight of an AW139 — the first of its kind for this helicopter model — in May 2025.

NEA’s autonomous system includes an autonomous software stack that can be integrated into current and next generation avionics, such as the Honeywell system featured on the AW139. Their technology includes some AI recognition techniques, but mostly relies upon object recognition, detection, avoidance and other smart computer vision techniques for autonomous navigation. A representative for Honeywell Aerospace explained in an emailed statement to A&DT how the AW139 was modified to enable the autonomous flight.

“The core advancement was the addition of NEA’s autonomy stack onboard the aircraft. This software is responsible for planning the mission, generating monitoring progress in real-time to make necessary adjustments,” the representative said.

“In a traditional setup, these commands would come from either a pilot or a flight management system. In this case, they were generated by NEA’s autonomy system and then executed by the Honeywell autopilot. To make this possible, Honeywell modified the aircraft wiring and interfaced the NEA autonomy system with the Primus EPIC avionics, allowing it to read data from the avionics bus and send commands directly to the Automatic Flight Control System (AFCS).”

During the flight, Honeywell’s autopilot was still responsible for flying the aircraft, while following target commands provided by NEA’s autonomous system. The representative further explained that the two companies are still exploring the form factors and embedded systems architectures that could be used to enable autonomy on military aircraft.

“Our joint focus is on developing autonomy solutions that are affordable, scalable, and certifiable, particularly for existing platforms. In many cases, that means integrating autonomy into currently certified hardware, minimizing the need for brand-new development or certification pathways,” the representative said. “However, autonomy is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Different missions — whether uncrewed cargo flights, optionally piloted ISR platforms, or future passenger-carrying aircraft — may require different combinations of software, sensors, compute, and flight control. In some cases, this could mean adapting an existing autopilot; in others, it could require new autonomy modules or compute systems.”

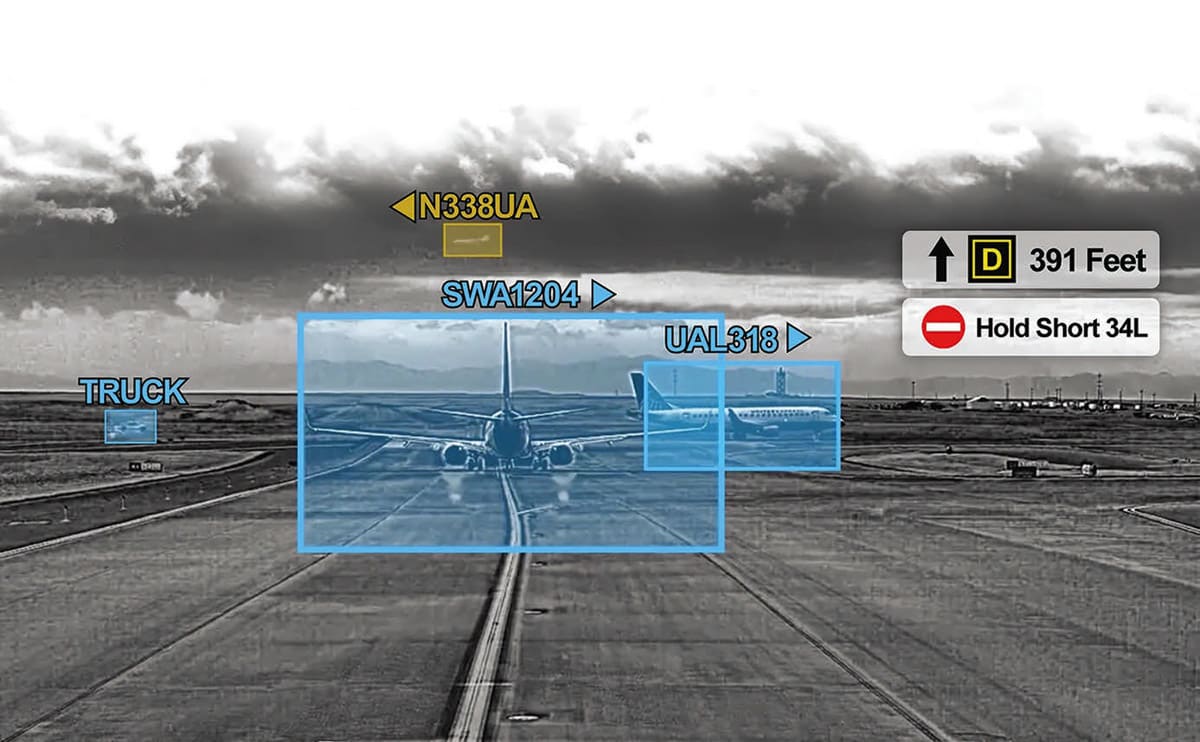

Universal Avionics is yet another company that is bringing AI to cockpit systems. At the 2024 National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) annual exhibition, Universal introduced its new “Aperture” technology, a small computer with enough embedded processing to enable real-time sensor fusion and AI-powered augmented reality for pilots. The Aperture computer fuses real-time video analysis from multiple aircraft cameras, and integrates Automatic Dependent Surveillance (ADS-B) information to provide pilots with visual instructions and cues on cockpit displays.

Universal’s software-based flight management system, iFMS, also features AI algorithms capable of performing various in-flight navigation tasks such as “FMS reprogramming, calculating efficient flight paths, analyzing various data inputs, such as weather patterns, air traffic, and aircraft performance parameters,” according to the company.

“Emerging technologies like AI offer immense potential for aviation. Instead of translating 2D screens into real-world situations, critical information is integrated into the pilot’s vision, augmented into the real world while looking outside the cockpit,” Dror Yahav, Universal Avionics CEO said in the company’s press release introducing Aperture.

Another avionics company that A&DT previously highlighted on this topic is Daedalean, the Switzerland-based company that has been working with several major aerospace companies in recent years on the use of ML and neural networks in avionics systems. In 2023 for example, Daedalean and Intel Corp. jointly published the whitepaper “The Future of Avionics: High Performance, Machine-Learned, and Certified.” The report proposes a collaboratively developed reference architecture for certifiable embedded electronics for AI-enabled avionics systems.

The Silicon Valley innovation wing of Airbus — Airbus Acubed — has been in data collection mode for several years now researching and developing the use of “smart automation functions” on aircraft, according to an emailed statement from Arne Stoschek, their VP of AI and Autonomy. The Acubed team of researchers and engineers have an ongoing focus on their “Wayfinder” initiative.

“We do test AI solutions in the sense that we have a fully functioning visionbased landing system that operates in real-time on the Acubed Flight Test Lab, our King Air. In terms of the specific avionics computers and hardware, the Acubed Flight Test Lab utilizes state of the art Garmin avionics including a radar altimeter and a digital autopilot to provide envelope protection for safety purposes,” Stoschek said. “Additionally we have installed twice as many cameras on the King Air to replicate the potential position on current A320 aircraft. These cameras provide the correct perspective for land vision-based functions to support taxi and takeoff. We utilize industry standard computers to record video and metadata (position, velocity and acceleration) information to improve vision labeling and accelerate AI development.”

The Wayfinder team is also working on an AI pilot decision assistant and exploring the development of an ILS type of pilot display for a visual landing function, Stoschek said. The type of research and development being conducted by Stoschek’s team should prove invaluable for the industry’s optimization of the use of AI in avionics systems in the future.

“What’s also interesting about our current Acubed Flight Test Lab is that we can push software code and updates from our office to our aircraft while in flight (in shadow mode meaning the development software doesn’t touch safety critical aircraft systems),” Stoschek said. “We can also download data from the aircraft to our office while in flight. This setup enables rapid software iterations and immediate exposure to real world flight conditions - we refer to it as aircraft in the loop development capability.”

This article was written by Woodrow Bellamy III, Senior Editor, SAE Media Group (New York, NY).

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...