Improving Thermal Seat Comfort

Optimizing climate seat systems requires increased complexity in seat design, which in turn is driving a need for more detailed thermal simulation methods.

The automotive HVAC system is the primary system responsible for controlling and maintaining thermal comfort of vehicle occupants. Heat transfer with vehicle seats, however, plays a significant role in the thermal experience due to its proximity and large contact area with the seated occupant. This contact not only exposes the occupant to the current thermal conditions of the seat but also tends to isolate affected body regions from the climate-controlled air provided by the HVAC system.

To increase customer satisfaction and improve thermal comfort, climate control components are often added to seats such as heating elements or ventilation ducts to complement the HVAC system, in effect, turning the seat into a secondary thermal control system. This design approach has the potential benefit of improving the fuel efficiency of the vehicle by better directing thermal energy to/from the occupants and reducing the energy requirements of the HVAC.

Experts from Hyundai-Kia America Technical Center Inc., ThermoAnalytics Inc., and Gentherm conducted a thermal simulation study aimed at improving the thermal seat comfort experience and energy usage of the automaker’s heated seating systems. Specific goals of the simulation were to identify opportunities for improvement in thermal exchange and sensation between the body and seat, and to compare thermal trends between different design conditions.

The thermal comfort problem at its core is a function of heat exchange between the environment and the human body. This exchange primarily occurs through convection with the ambient air, conduction with contact surfaces, evaporation of sweat from the body, and radiant heat loss to or gain from nearby materials.

When considered in these terms, the seat is just a part of the environment. The difference between seated contact area versus other parts of the thermal environment is vehicle seats tend to have larger contact surface areas with the human body. These contact surfaces increase localized conduction and reduce convection producing localized microclimates.

The most important aspect of thermal sensation is it varies across the body and localized thermal regulation changes as the body adapts to the environment. Consequently, the perception of microclimates produced from sitting will be perceived differently across the body and change as the body adapts.

Thermal simulation method

Simulations of this highly complex system were based on ThermoAnalytics’ RadTherm Model, RadTherm’s Human Thermal Model, and UC Berkeley’s Thermal Comfort Model. The RadTherm thermal analysis tool was used to model conduction, convection, and radiation between the seat, occupant, and environment. RadTherm’s human thermal module was used to predict physiological effects including metabolic heat, thermoregulation, etc. The Berkeley model was used to predict local and overall perceived thermal sensation and comfort.

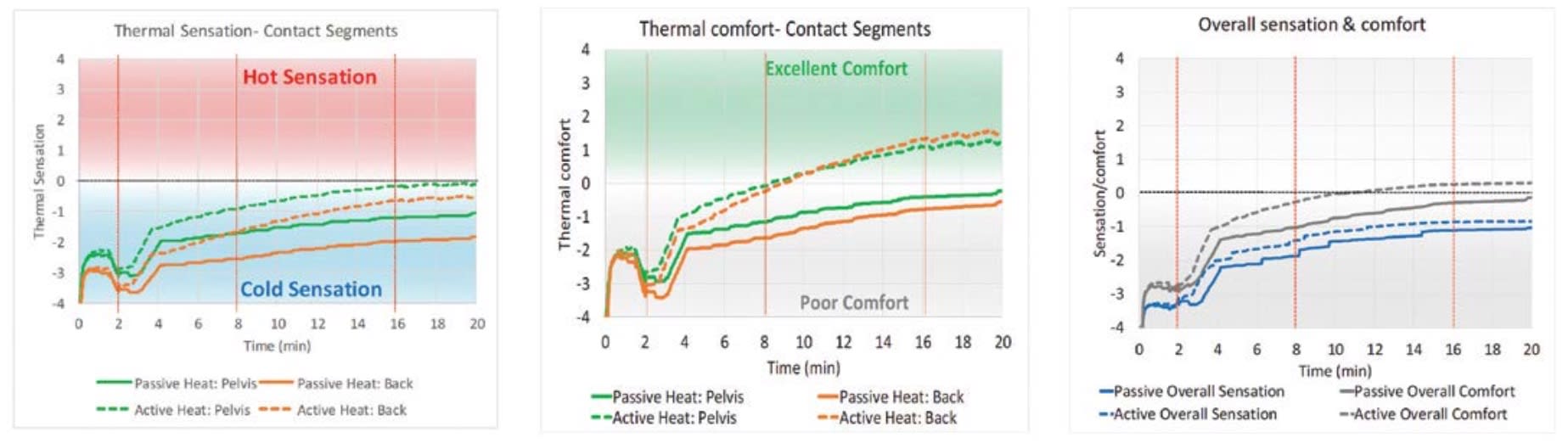

The Berkeley model distinguishes 16 local body regions in static, transient, and localized heating/cooling scenarios. The output relates to subjective ratings of two concepts: Thermal Sensation and Thermal Comfort for the local body parts as well as the overall body. In this model, sensation is related to “How hot or cold a body part is perceived to feel” and comfort is related to “Whether the sensation makes the person feel good or bad.”

The challenge was how to set up and apply these models used for general simulation of thermal transfer and full body thermal comfort to be more directed at seated thermal comfort.

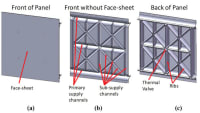

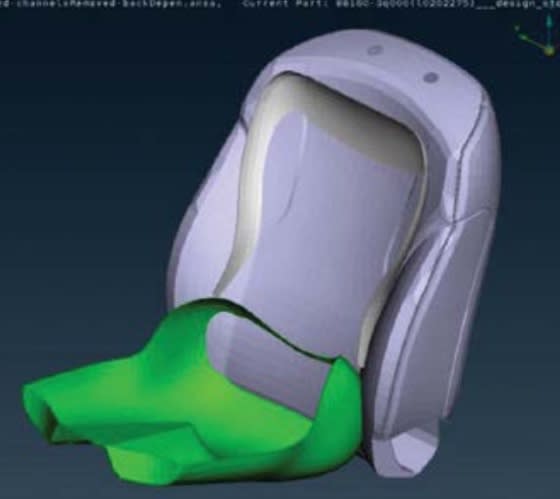

The Hyundai Sonata’s seat was selected for this simulation, and only the seat A-surface (top seating surface), the foam pad, and portions of the frame were required for the model. The seat frame is not included in the simulation and is only used to define a backstop for seat deformation. Small fasteners, cables, and other parts not relevant to thermal analysis were removed in CAD. The final data seat was meshed and exported into ANSA.

The next step was to modify the 3D geometry to represent the shape of the components under a loaded, compressed condition. For the purposes of this simulation it was determined that the Sonata design penetration from the SAE H-point manikin would be acceptable as a repeatable, meaningful metric for comparison. This was accomplished by importing the H-point surface geometry located at design coordinates into ANSA. The de-penetration tool in ANSA was then used to deform the seat cover to match the H-point surface geometry. ANSA direct morphing was then used to de-penetrate the foam pads to fit the deformed seat cover.

The next step was to add the heating element between the trim cover and foam pad. The element path was traced and projected onto a surface in ANSA. Direct morphing was then used to fit the element to the seat cover. The final element path is completed using the diameter of the wire.

This compressed shape is critical to the simulation because it determines the contact points for heat conduction with the body and it also identifies changes in component density from an uncompressed state to the actual loaded condition.

A mid-sized male manikin was selected as the initial basis for the 3D human body. This body type closely matches the SAE H-point device’s weight and hip breadth used to set the loaded seat shape. The original geometry was created in POSER using a male height of 1699 mm (66.9 in).

The manikin was positioned and posed based on the H-point design criteria (design thigh angle, torso angle, and floor height). A manikin mesh was then imported into ANSA where the manikin’s back and buttock shapes were morphed to fit SAE H-point surfaces more precisely. Finally, the manikin was separated into individual segments required for localized thermal modeling.

Case study environment

The case study selected for this simulation was a warm-up scenario starting from an extremely cold environment. The initial ambient temperature and seat material temperature are -20°C (-4°F). A relative humidity of 40% was assumed constant throughout the simulation.

The test manikin is exposed to this initial environment for 60 sec before the start of the test to simulate an individual walking outside to their car. To account for influence of the HVAC system, the ambient air warms up at a predetermined rate reaching 19.1°C (66.4°F) after 15 min.

In this scenario, the metabolism of the 50th percentile height and weight male is assumed to have an activity level of 1.2 metabolic equivalent, which corresponds to light activity (standing, relaxed). Appropriate clothing was also applied: long-sleeve thick-knit sweater, thick-knit hat, loose tweed trousers and briefs, dress socks, and street shoes. This is used to compute local insulative effects of clothing across the body and provides a whole body insulation value of 1.24 clo (0.192 m2-K/W).

Dimensional properties of the seat are extracted directly from the 3D geometry of the components. Additional information not available in CAD was required for the simulation to describe the thermal characteristics of the materials, specifically material density, thermal conductivity, and specific heat.

For the purpose of this simulation, simple estimates were used since the analysis focuses on general trends in a seating system’s heat exchange rather than specific performance of the Sonata’s seat heater system. Material components modeled include trim cover, ventilation/plus pad layer, cushion heating element, seatback heating element, and foam pad.

Both passive and active heating control schemes are simulated. In the passive simulation, the heating elements are left inactive to assess heat transfer from the body and environment only. In the active seat heater simulation, the heating elements are turned on to assess heat transfer between the body, environment, and the seat.

The simulated heating rate and maximum set temperature of the seat heater system correspond to the program specifications. In addition, the seat heater cycles on and off to maintain maximum set temperature. The seat temperature will be evaluated at the trim cover immediately adjacent to the heating element.

Simulation results

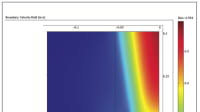

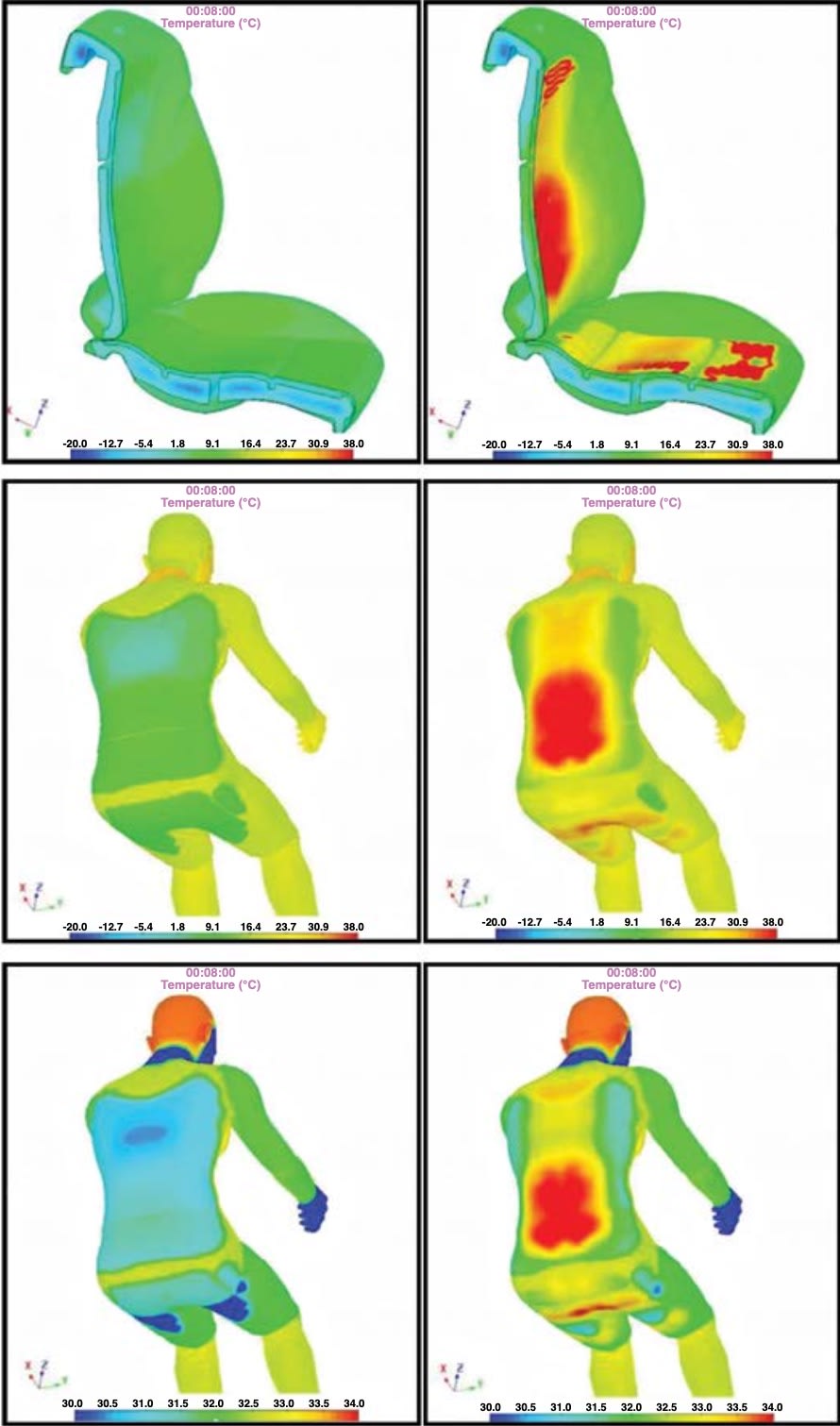

Temperatures across the seat trim cover, in the clothing, and on the skin were measured over 20 min in the simulation. Several key results are noted:

- The passive system and the active heat system both experienced warming during the simulation

- The active heat in the cushion reached the maximum set point temperature of 42°C (108°F) at the cover in about 6 min (faster than the passive case)

- The passive seat system still warmed up significantly to 10°C (50°F) in about 11 min from body heat and ambient air alone

- Areas of body contact distribute heat faster and more evenly due to the influence of heat conduction

- Noncontact areas take longer to heat up in the passive system and in the heated system show more delineated heat distribution from the elements.

The Berkeley model converted skin and whole body temperatures into predicted subjective output. Notable results include:

- There is a significant drop in thermal comfort and sensation in the pelvic and back regions at 2 min for both systems as heat moves from the occupant to the colder seat

- Thermal comfort for the seat contact regions of the passive system begin to increase after 4 min but never reaches neutral after 20 min

- Thermal comfort for the seat contact regions crosses over to comfortable at about 8 min in the active warm-up system.

The results of this study showed thermal comfort and seating effects are highly dependent on two key factors: environmental and human factors. Environmental factors in this case include typical material properties related to heat exchange but also include deflection and compression properties of the seat that effect density and contact area. The human factors of size, physiology, clothing, activity level, and posture relate to the potential heat output of the individual and the potential seat contact area.

Modeling and simulation of these factors identified several critical heat transfer details, namely:

- Clothing properties appropriate for environmental conditions are not uniform across the body or seat contact regions

- Distribution of thermal energy from and to the human body is not uniform

- Loaded (compressed) material properties are important for primary contact regions because they may change many heat transfer characteristics

- Typically the back, chest, and pelvis were the most influential to overall sensation.

The results of this project showed that a thermal modeling process using RadTherm can be used to simulate the seated thermal heat exchange. The H-point design information was an important component needed to define meaningful deflection and contact area with the seat.

This feature is based on Ziolek, S., Pryor, J., Schwenn, T., and Steinman, A., “Heated Seat Simulation Study for Thermal Seat Comfort Improvement,” SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars - Mech. Syst. 8(2):2015, doi:10.4271/2015-01-1391.

Top Stories

INSIDERDefense

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

Road ReadyTransportation

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Power

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Connectivity

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Transportation

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Aerospace

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance