Tailoring Fuel Injection to Control NOx

The next big step to help heavy-duty diesel engines meet stricter emissions regulations involves adapting the fuel-injection system to the combustion needs.

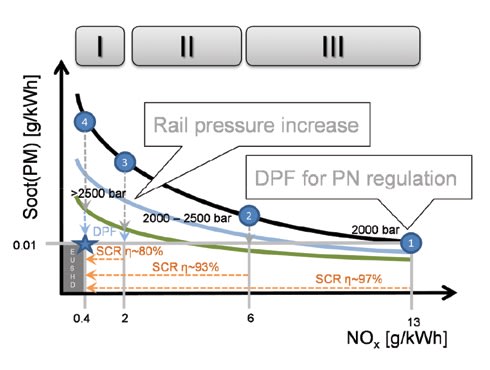

Future diesel engine legislation, such as the EU’s Stage V and possible Tier 5 in the U.S. for off-highway, demand further improvements to reduce CO2 while keeping the already-low NOx emissions levels. For on-highway trucks in the U.S., a stricter limit of 0.2 g/bhp-hr NOx emissions needs to be achieved, with even tougher ultra-low NOx limits on the horizon. In this trade-off, system costs and complexity of the aftertreatment are defining the constraint in which the common-rail fuel injection system layout is defined.

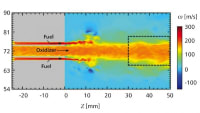

In the past, the increase of rail pressure was the major step to control the soot emissions in view of low engine-out NOx emissions by applying massive EGR (exhaust gas recirculation). With the on-going development of NOx-aftertreatment by selective catalytic reduction (SCR), conversion efficiencies of up to 97% allow a reduction in the EGR and rail pressure usage. In that context, the steepness of injection rate, the nozzle flow rate and the injection pressure are remaining parameters to control the NOx emissions. A shallow injection rate in combination with larger nozzle flow rates is beneficial to reduce the NOx emissions thanks to a reduced premixing of fuel with air.

To study this effect, researchers from Denso utilized the latest solenoid injector with improved magnetic actuation. The influence of the steepness of injection rate is studied on a six-cylinder heavy-duty diesel engine on three representative part-load points of the WHSC (World Harmonized Steady state test Cycle). Depending on the engine-out NOx emissions requirements, two scenarios are considered. In case of a strong NOx aftertreatment, the shallow injection rate steepness is beneficial for the fuel consumption. In case of less NOx aftertreatment, high EGR rates are required and soot emissions can be controlled through the steepness of injection rate.

Denso experts presented this research as part of the “Combustion in Compression-Ignition Engines” technical session at April’s WCX17: SAE World Congress Experience in Detroit.

Diesel fuel injector technology

The combustion process of the diesel engine directly depends on the performance of the fuel-injection system, particularly on injector performance with regard to the steepness of the injection rate and minimum hydraulic interval, and the maximum rail pressure level. In the past, the increase of rail pressure was the key to control the air entrainment and the premixed combustion portion. This premixing combustion increases the combustion noise but also reduces the soot emissions as the air is entrained into the fuel rich zones.

The increase of injection rate steepness has a similar effect. Using a quick needle opening, pressure losses by the needle seat throttle are reduced, especially in the case of pilot injection events. The rail pressure is utilized more efficient for the spray momentum and enhances the air entrainment of the spray. Similar to the rail-pressure increase, this leads to the increase of a premixed combustion and reduces soot emissions by entraining the air into the rich fuel areas. Such quick injection opening and high rail pressure is required in engine concepts with high EGR usage to reduce NOx emissions — but combustion noise increases. To countermeasure the combustion noise, the premixed combustion therefore has to be limited, even in the presence of high rail pressures. This approach is realized by employing the flexibility of the injection system to increase the number of injection events and to achieve short hydraulic intervals.

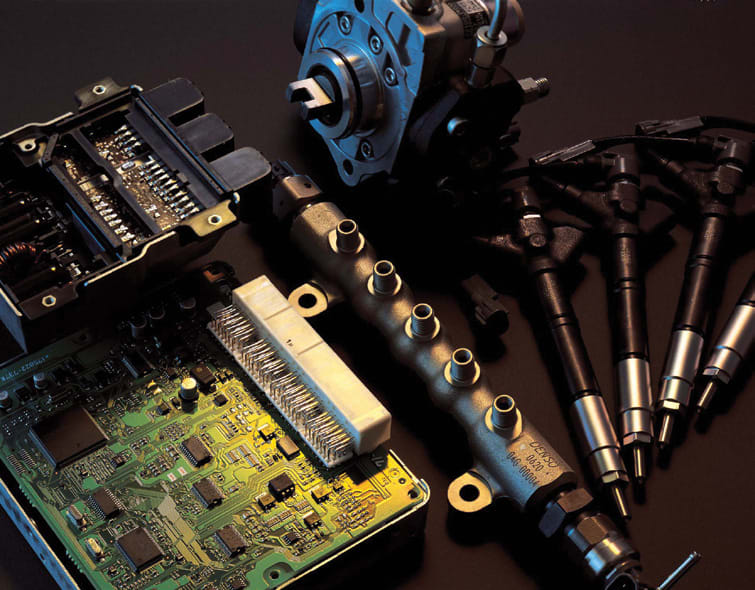

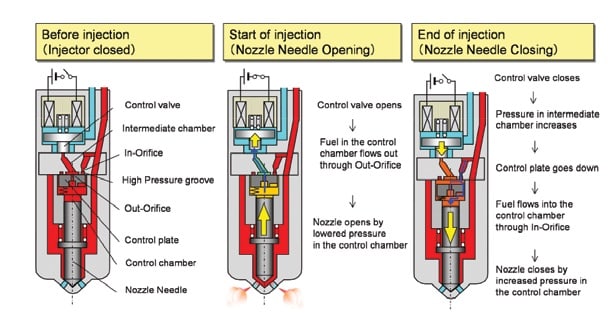

Such a concept already was developed and tested by using piezo servo valve technology for passenger-car applications, and studied by trial samples for solenoid injectors for passenger car and heavy-duty diesel engine tests. Now this technology is further improved through the ongoing development of new solenoid actuators. The G4S injector functionality during start-of-injection and end-of-injection is pictured.

A small control plate separates the high- and low-pressure areas and has the function of a three-way valve. The switching is released through the movement of the control plate. The pressure decrease is defined by the flow-rate characteristics of the out-orifice, which is part of the control plate. It is therefore the flow characteristics of the out-orifice to define the needle opening speed. To improve the needle opening speed, this flow-rate characteristic of the out-orifice was increased while keeping the flow rate of the inlet orifice constant.

In addition, the intermediate chamber volume and sub-orifice diameter were increased to avoid a throttling downstream, but causes an increase of the pressure forces on the control valve. As a consequence, the spring set force is increased against which the magnetic force acts during actuation. Therefore, the magnetic force had to be increased by changing the solenoid material. As a result of these improvements, the injection rate steepness could be increased while the closing speed controlled through the inlet orifice flow rate and motion of the three-way valve were kept the same.

The increase of the out-orifice flow rate achieves a shorter hydraulic interval. The standard solenoid injector for passenger-car applications achieves in best case a hydraulic interval of 200 μs.

Hydraulic performance was investigated on a pump bench. For analyzing the minimum hydraulic interval, three consecutive pilot injections are applied followed by a main injection. Within the standard G4S specification, the min. hydraulic interval of 250 μs is achieved. With increased out-orifice diameters, a much shorter hydraulic interval of 100 μs is feasible. Overall, the injector’s performance demonstrated that the 3-way valve allows the adaption of the out-orifice flow rate independent of the in-orifice throttle by utilizing a new solenoid actuator.

The performance of the improved solenoid injector was evaluated on a heavy-duty EU6 diesel engine (see table for details). The engine was equipped with a high-pressure fuel pump (HP6: 2 cylinders, 3 lobes) with a maximum rail pressure of 300 MPa. All cylinders are instrumented by pressure transducers (Kistler 6053CCsp) to analyze the combustion cycle individually. For engine testing, five operating points of the World Harmonized Steady state test Cycle (WHSC) were selected. These points cover the area of low part-load, mid part-load and full-load engine operating conditions. NOx emissions are controlled by utilizing the high-pressure exhaust gas recirculation (HP-EGR).

Multiple-injection strategy

Several injection strategies at short hydraulic intervals were evaluated at several load points. Because the optimized emission trade-off depends on many variables, a DoE (Design of Experiments) was performed for each injection strategy. As inputs for the DoE, the rail pressure, injection timing and pilot quantities were varied. From this data a Gaussian model was created. After confirming the model’s accuracy, this model was used to find the best brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC)-NOx trade-off within a given soot constraint of 0.02 g/kWh. To evaluate the necessity of short interval, the hydraulic interval was varied as an additional input variable during the single pilot injection DoE.

Already from the optima, block and single pilot injection display a low rail pressure 60 MPa, whereas the double and triple pilot injection strategy uses higher rail pressure. The reason for this increased rail pressure is (1) to satisfy the given soot constraint and (2) to not extend the combustion duration too much by additional pilot injections. Subsequently, these optima were validated on the engine by a center-of-combustion (CoC) variation.

It turns out that the single pilot injection strategy achieved the best BSFC-NOx trade-off. The first pilot quantity triggers the combustion and enables the early ignition shortly before engine top dead center (TDC). At lower NOx emissions — achieved by retardation of injection timing — the single pilot injection shows even increased benefit in the BSFC-NOx emissions trade-off. At retarded injection, the single pilot ensures that the combustion occurs near TDC by a relatively large pilot quantity in combination with larger hydraulic interval.

The double pilot and triple pilot injection strategy do not really influence the heat release, and a single pilot injection strategy is sufficient for a smooth shape of the heat release rate.

At the higher speed, part-load operating point WHSC3, a similar DoE approach was conducted. The optimum at WHSC3 showed smaller pilot quantities for all injection strategies and a short interval in the case of single pilot injection compared to the WHSC12 engine load point.

The optima of this engine operating point WHSC3 again are evaluated on the engine through a CoC variation. Similar to the engine load point WHSC12, soot emissions are again below the DoE constraint of 0.02 g/kWh thanks to an overall air-fuel ratio of λ=2.17. Therefore, the optima from each injection strategy do not affect the soot emissions.

In this load point, block injection, single pilot injection and triple pilot injection strategies achieve a similar emissions trade-off. At this speed and load, the pressure trace is already shallow for the block injection. Therefore, the addition of the pilot injections cannot shape the heat release rate and the ignition occurs closely to engine TDC.

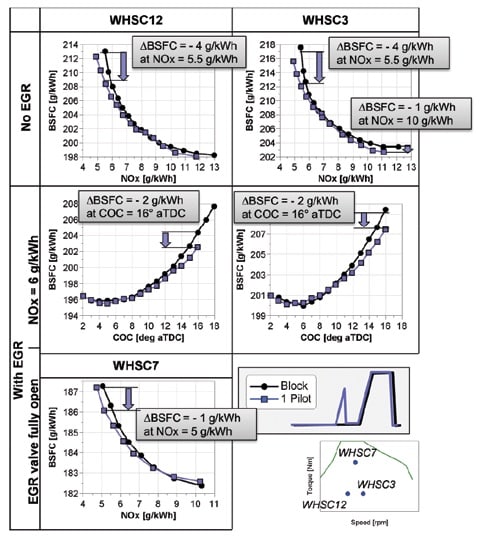

A similar result was achieved for part-load operating points with EGR and including the WHSC7 part load point. For the low load conditions (WHSC12 and WHSC3) the EGR rate was varied to obtain a constant NOx emission of 6 g/kWh. At WHSC7 the EGR valve was set fully open and NOx was varied by retardation of the combustion timing. Compared to the block injection, the single pilot injection strategy improves the fuel consumption by max. 2 g/kWh with EGR and max. 4 g/ kWh without EGR.

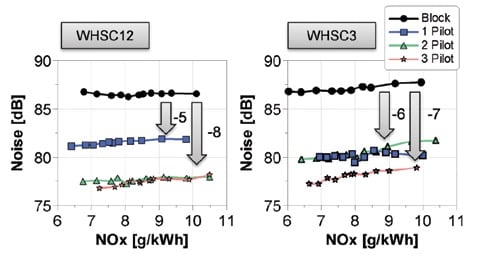

Whereas the single pilot injection leads to the best BSFC-NOx trade-off on this heavy-duty engine, additional injections become more interesting when engine noise might become limited — e.g., by future emissions legislation or hybrid application. Data shows a significant noise reduction by adding a single pilot injection. Adding additional pilot injections in combination with noise-optimization could further reduce the combustion noise.

Injection-rate steepness

Three different types of injection-rate steepness — fast needle opening, standard needle opening and slow needle opening — were investigated at two different levels of raw engine-out NOx emissions. The NOx emission level is again controlled by the EGR rate.

At NOx=6 g/kWh, the optimum BSFC is between 4 and 6°CA aTDC. Still the engine has sufficient air remaining and the influence of the injection rate is minor. Increasing the EGR to NOx=2 g/kWh, the shallow injection rate cannot sufficiently entrain the air, and soot increases significantly. In this case, the countermeasure to increase the rail pressure by 40 MPa still exists.

This is a common approach to balance the injection-rate steepness by rail pressure. Both controls the amount of air entrainment and hence the local mixing from the charge into the fuel spray. On the other hand, the EGR could be reduced or omitted to have sufficient oxygen and reduce the soot emissions. Here the NOx engine-out raw emissions must be converted through the aftertreatment. NOx levels of 13 g/kWh require an SCR conversion efficiency of ~97%. In such a scenario, the BSFC is further improved when applying a slow needle opening rate.

Soot emissions are at the limit of detection. As EGR is decreasing the combustion duration is shortened regardless of the needle opening speed, and BSFC could be improved by 2 g/kWh.

Such improvement of a scenario with less EGR and reducing the needle opening speed does not necessarily deteriorate the rated power performance. BSFC could be enhanced by increasing the rail pressure for both fast and slow needle openings. It is interesting to note that although NOx emissions increase with the higher rail pressure, the shallow injection rate by the slow needle opening counters this effect and gives a small benefit in NOx of 1 g/kWh.

Nozzle flow rate

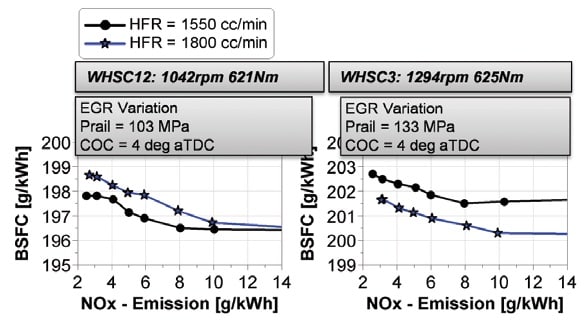

In the scenario that the EGR is reduced by the SCR and soot emissions becoming very low, the nozzle flow rate can be adapted to the raw engine-out NOx and soot emissions. Typically, the nozzle flow rate should be small to reduce the spray penetration and limit the soot formation but sufficiently large to supply the fuel to achieve the full load engine performance. Under the constraints of high NOx levels and sufficient oxygen, soot emissions are not limiting the increase of the nozzle flow rate and the demand of rail pressure is reduced. Then nozzle flow rate could be increased to reduce the combustion duration. Both the reduction of rail pressure and increased flow rate are mechanisms that shorten the combustion duration and improve the fuel consumption in terms of BSFC.

This approach was evaluated on the engine. Increasing the flow rate from 1550 to 1800 cc/min, the BSFC was improved by 0.5% at WHSC3. At lower engine speed conditions of WHSC12, the BSFC is similar at high NOx emissions but increases at low NOx emissions.

At the rated torque engine operation, the shorter combustion duration also improves the fuel consumption without a penalty in the soot emissions. Here the CoC is limited only by peak firing pressure (PFP) and an improvement of fuel consumption by 1% is achieved at similar soot emissions. A penalty results in the NOx emissions, which are increased by 1 g/kWh due to the increase of the spray penetration and premixed combustion amount.

However, this increase of NOx emissions only appears at 136-MPa rail pressure. Toward a rail pressure usage of 180 MPa, the BSFC is further improved and NOx increases by 2 g/kWh. This behavior could be explained by the increase of maximum heat release and a shorter combustion duration with respect to the increase of rail pressure and the increase of nozzle flow rate. A further increase to 250 MPa does not improve the air utilization for either nozzle.

For rated-power operation, fuel consumption also is improved by increasing the rail pressure from 180 MPa to 250 MPa; an increase to 300 MPa does not further reduce fuel consumption. At these conditions, the increase of nozzle flow rate does not demonstrate an additional positive effect on the fuel consumption, although the 1800 cc/min nozzle has a shorter combustion duration by 2°CA and an increase of maximum heat release rate, meaning the formation of increased NOx emissions.

This article is based on SAE Technical Paper 2017-01-0705 written by Jost Weber, Olaf Herrmann and Ron Puts of Denso Automotive Deutschland GmbH, and Jyun Kawamura, Yasufumi Tomida and Makoto Mashida of Denso Corp.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...