High-voltage Hybrids

FEV engineers evaluate 48V and high-voltage parallel hybrid architectures for Class 6-7 commercial vehicles. Certain setups show more promise than others.

The level of electrification for medium- to heavy-duty trucks will vary based on their application. For example, a Class 8 long-haul truck that operates at cruising speed for most of its drive cycle could benefit from a 48V mild hybrid configuration and accessory electrification. Class 3-7 vocational trucks operating at relatively low speeds and experiencing frequent start-stops can achieve a 15-25% fuel efficiency improvement from the application of a mild or full hybrid system. Class 3-7 vocational applications are also suitable candidates for battery- and fuel cell-electric powertrains and range extenders.

The general trend and guidelines for electrification on passenger cars/ light trucks may not be valid for Class 3-7 urban vocational vehicles, as the segment faces specific challenges including lower production volumes, lost payload, durability requirements, varying packaging constraints, varying operating vehicle weight, long vehicle useful life, wide range of operating drive cycles, and engine exhaust gas aftertreatment performance requirements. In this evaluation conducted by experts at FEV North America, four different parallel hybrid architectures (P1, P2, P3, P4) for Class 6-7 vocational applications were analyzed at two different voltage levels: ≤48V (mild hybrid) and >150V (full hybrids).

The baseline vehicle for the Class 6-7 vocational truck — a dynamic one-dimensional vehicle model of a Freightliner M2 106 with a Cummins ISB 6.7-L diesel engine and an Allison 2000 Series 6-speed — was developed using GT-SUITE by Gamma Technologies. After correlating the baseline vehicle to experimental data, the model was updated with hybrid components. Performance of the hybrid layouts was evaluated on the ARB Transient and real-world drive cycles, and key trade-offs were identified between fuel consumption, initial investment cost, payback period and freight efficiency.

Hybrid powertrain integration

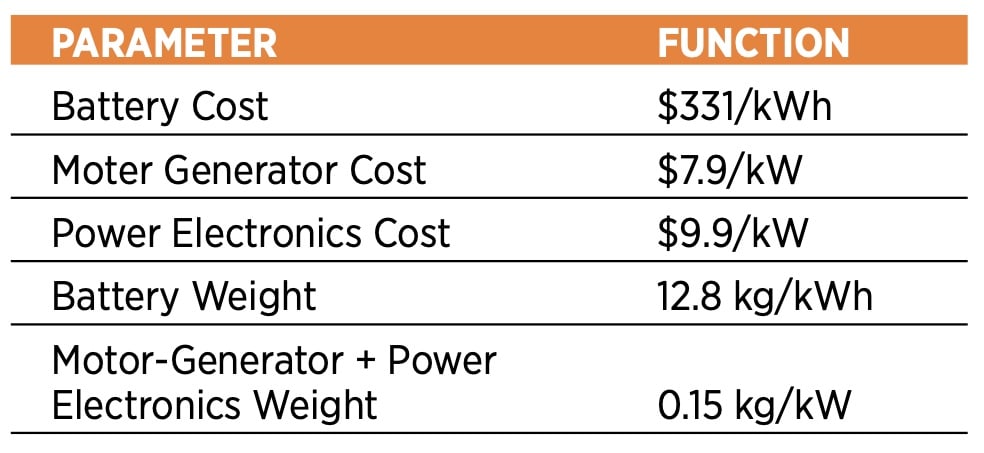

The baseline model was integrated with a motor-generator, gearbox, power electronics, lithium-ion nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC) battery, battery-management system, engine clutch and a supervisory control strategy. An optional starter motor was implemented based on the maximum motor-generator torque, whereas a DC-DC converter replaced the lead-acid battery from the conventional vehicle model.

For the P1 parallel hybrid architecture, the engine was directly connected to a motor-generator unit, which was then connected to the transmission through the torque converter and a lockup clutch assembly. The motor-generator unit acted as an engine starter along with providing additional torque during acceleration to assist the engine and perform load shifts. During vehicle deceleration, the motor-generator unit also acted as generator for energy recuperation.

In the P2 parallel hybrid architecture, an additional clutch and a motor-generator unit were introduced between the engine and the transmission. The clutch was connected to the engine and the motor-generator was connected to the transmission through the torque converter and a lockup clutch assembly. The introduction of the clutch between the engine and the motor-generator allowed the engine to shut down during deceleration and improved energy recuperation compared to the P1 setup.

The P3 parallel hybrid architecture was developed by connecting the motor-generator unit to the transmission output shaft with a clutch. A starter motor was applied for engine starting. The P3 parallel hybrid architecture provided the opportunity for the highest energy recuperation, as the driveline could be disconnected during deceleration and braking events. Finally, in the P4 parallel hybrid architecture, two motor-generators were directly coupled to the front axle of the vehicle. Again, a starter motor was included for engine starting. The P4 architecture allowed for four-wheel-drive capability.

Axial-type permanent-magnet BLDC (brushless direct current) technology was selected for the motor-generator due to its high efficiency, higher torque output and packaging advantage. A map-based motor-generator model was developed with specified maximum and minimum torque curves and combined motor-inverter efficiency. Maximum motor-generator torque during charge (1C) and discharge (3C) operation were also limited by battery capacity. Efficiency values for the motor maps were scaled using global factors based on operating voltage and motor-generator maximum speed. The scaling factors were derived from measured data from different axial BLDC motor-generators operated at different voltage levels and maximum speeds.

The NMC battery technology was chosen for this application due to its higher specific capacity. A Thevenin electrical-equivalent circuit-based battery cell was modeled by specifying the open-circuit voltage, series internal resistance and RC branches to model the electro-chemical dynamics. Battery cell state of charge (SOC) also was modeled using the default approach available within GT-SUITE.

Battery cells were arranged in series and parallel to vary battery voltage and capacity. Battery cooling and cell balancing were not considered in this study; however, a battery management system was introduced to restrict battery terminal voltage and current to their acceptable hardware limits. In addition, a cell aging model was implemented to predict battery capacity deterioration over time, based on depth of discharge, average voltage and current.

A constrained on-off control strategy was selected for parallel hybrid powertrain management. The control strategy determines the power split between engine and motor-generator based on the torque demand and battery SOC. A rule-based control strategy was selected over model-based optimization strategies, such as equivalent charge minimization strategy, due to the computational limits of the engine control unit. Hysteresis loops were also implemented to prevent frequent engine start-stops between various control modes.

Results of DoE analysis

The optimization for each hybrid configuration was carried out on the ARB transient cycle. A five-variable DoE (design of experiments) was conducted for each parallel hybrid configuration at two different voltage levels (see Table 2). The results were optimized using the FEV xCAL DoE tool.

Figure 3 compares the fuel consumption reduction, battery capacity, battery voltage and motor power for the four different parallel hybrid architectures at two different voltage levels against the total payback period. For each configuration with the 48V mild hybrid system, only one unique solution is presented, representing the maximum fuel consumption reduction within a two-year payback period.

For the full-hybrid configuration, multiple battery capacity, voltage and motor solutions are presented based on the different payback periods.

When comparing the various architectures at higher voltages (>150V), the 350V P3 configuration provides the maximum fuel-consumption (FC) benefit across the complete range of payback periods considered. The higher FC reduction with the 350V P3 configuration is achieved due to the integration of the electric motor after the transmission. In the P3 configuration, the electric motor is able to achieve higher regeneration efficiency due to the elimination of the losses from the transmission and engine during regeneration when compared to the P1 and P2 configurations.

The P4 configuration, which provides the maximum regeneration capability, shows limited FC reduction due to the relatively lower motor power applied. In the P4 configuration, the maximum applied motor speed is limited due to the gear ratio limit of 8:1, which therefore limits the maximum power capability.

In the 48V configuration, the P2 and P3 configurations demonstrate a similar fuel consumption benefit. In both configurations (P2 and P3), the motor rated power is limited to 8.9 kW. If a motor with higher rated power is applied in the P3 configuration, it results in improved FC reduction, but the two-year payback period criteria is not satisfied. Even though both 48V P2 and P3 configurations show similar FC benefit, the P3 solution is preferred due to the lower battery capacity and therefore a lower payback period of less than one year. Further comparison of the total added weight and cost for the two P3 configurations reveals that the 48V mild-hybrid solutions result in a much lower initial investment of less than $2,000 compared to more than $4,000 for the full hybrid. Another advantage of the 48V mild-hybrid application is the lower payload penalty due to negligible increase in added weight (Figure 4).

Figure 5 compares the CO2 reduction and freight-ton efficiency improvement for the four unique 48V configurations shown in Figure 3, along with all four full-hybrid configurations with a two-year pay-back period. The highest CO2 reduction of 24% is achieved with the P3 full-hybrid configuration; however, the P3 48V configuration also shows an 18% reduction in CO2 emissions. When considering the Phase-2 GHG regulations for Class 6-7 urban vocational applications, highlighted in Figure 6, a 48V P3 configuration is capable of achieving the CO2 reduction targets.

The freight-ton efficiency improvements also show a similar trend as the CO2 reduction, where the P3 350V full hybrid shows the largest improvement, at 33%, for the full-hybrid configurations. A 48V mild-hybrid system provides a 24% freight-ton efficiency improvement.

Figure 7 compares the load shift on the engine operating map for the ARB transient cycle for two optimum P3 configurations: 48V and full hybrid with a two-year payback period. For the 48V P3 hybrid configuration with limited electric-motor power capability, the hybrid controller is able to eliminate the engine operation at low to medium speed (700-1,500 rpm) and low loads (under 100 Nm).

When applying a 350V P3 hybrid configuration, the 30-kW electric motor is able to replace a larger area of the engine operation on the ARB Transient cycle, thereby resulting in a higher fuel consumption benefit and a CO2 emission reduction. Referring again to Figure 5, as the payback period criteria is relaxed, the battery voltage increases and allows the application of higher-power electric motors. The larger electric motor allows for a further replacement of the engine operating point resulting in an increase in fuel-consumption benefit.

A further comparison of the 48V and full-hybrid P3 configurations in terms of energy losses is highlighted in Figure 8. The P3 full hybrid shows considerably lower engine losses due to the shift in engine operating profile as highlighted in Figure 7. The energy losses in the hybrid component and transmission are comparable between both configurations. Overall, for the P3 configuration, the full hybrid shows 0.8 kWh lower energy losses when compared to the 48V mild hybrid solution.

Figure 9 compares the cost of ownership between the two P3 configurations against the baseline diesel vehicle. The 48V P3 mild hybrid configuration shows the lowest cost of ownership at the 8-year mark. The 48V mild hybrid benefits from the lower operating and maintenance costs when compared to the full hybrid application, while also performing significantly better in terms of the fuel cost when compared to the base-line diesel vehicle. The payload penalty with the 48V concept also is minimal due to a limited increase in weight.

On the other hand, the P3 full hybrid has the highest cost of ownership mainly from higher operating and maintenance costs not sufficiently offset by the reduced fueling cost when compared to the 48V P3 mild-hybrid configuration.

Real-world drive cycle

To this point, the analysis for the different hybrid architectures has been conducted on the ARB transient cycle, which has relatively high weighting for determining the CO2 emissions for vocational applications. However, the end user is concerned about FC improvements and subsequent return on investment on customer specific routes. To consider this impact, a custom drive cycle was developed using the GT-RealDrive feature.

The cycle was derived based on a typical operating profile experienced by a Class 6-7 delivery truck. The cycle considered included considerable low-speed operation during city delivery with specific times of vehicle stop. Figure 10 compares the CO2 reduction and freight efficiency improvement for both P3 configurations on real-world drive cycle. When compared to the ARB transient cycle, both P3 configurations show higher CO2 reduction and freight efficiency improvements on the real-world drive cycle.

For the P3 48V configuration, the CO2 reduction improved by 2% for the real-world drive cycle when compared to the ARB transient cycle. The higher CO2 reduction also leads to improved freight-ton efficiency. When compared on the real-world drive cycles, the difference in CO2 improvement between the P3 mild hybrid and full hybrid application is 3%, compared to the 6% difference when evaluated on the ARB transient cycle. These results further highlight the importance of considering both certification and real-world drive cycles when optimizing hybrid architecture/component specifications.

To further evaluate the potential of a 48V mild hybrid for heavy-duty applications, future studies will focus on evaluating the P3 mild-hybrid architecture for Class 4-5 and Class 8 long-haul applications. Studies also will focus on evaluating the use of a 48V belt starter generator with a P3 mild hybrid architecture for Class 4-8 applications.

This is a condensed version of SAE Technical Paper 2021-01-0720, written by Mufaddel Dahodwala, Satyum Joshi, Fnu Dhanraj, Nitisha Ahuja, Erik Koehler, Michael Franke, and Dean Tomazic of FEV North America Inc. It can be ordered or downloaded from SAE International at www.sae.org .

Top Stories

NewsRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsPower

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

ArticlesAR/AI

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Automotive

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Transportation

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Transportation

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Energy

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance